This is one in a series of essays on important works of Korean cinema available free to watch on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel. Previous selections include The Shower, The Road to the Race Track, Yeong-ja’s Heydays, Deep Blue Night, Aimless Bullet, Iodo, 301, 302, The March of Fools, Seopyeonje, Wangsimni, My Hometown, Madame Freedom, Chil-su and Man-su, and Night Journey. You can watch The Insect Woman here.

Now that K-pop, K-drama, and K-beauty have been international phenomena for years, Westerners must prepare themselves for the reign of the K-grandma. I’ve heard that label, or rather its more Korean form K-halmeoni, applied to Youn Yuh-jung, a veteran actress famous here in Korea since the 1970s. Much more recently she’s become a star in the United States as well: the anointment occurred last month, in the form of an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress granted for her performance in Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari. Much lauded even before the Oscars, Chung’s film tells of a Korean immigrant family struggling to make a go as farmers in the Arkansas of the 1980s. Youn plays the mother-in-law brought over from the old country to watch the children; at first an alien presence to the American-born young son, this foulmouthed grandmother comes ultimately to provide just the kindness and encouragement he needs.

Though perhaps not a role that will win any awards for originality, as written by Chung (in a “semi-autobiographical” script) and played by Youn it has resonated with viewers Korean and non-Korean alike. Increasingly many of the latter have been moved to watch Minari expressly in order to see Youn’s performance, so endearing a personality has the actress displayed in her post-Oscar interviews. An immigrant to the United States herself during a decade of “retirement” from the mid-1970s through the mid-80s, she’s spoken playfully and often sardonically in English about the rigors of low-budget independent filmmaking, Western mispronunciations of her name, and her desire to meet absentee producer Brad Pitt. As she accepted her Academy Award, she dedicated it to “my first director, Kim Ki-young, who was a very genius director. I made my first movie with him. He would be very happy if he is still alive.”

Released exactly half a century earlier, that first movie Woman of Fire (화녀) features a 23-year-old Youn playing a femme fatale who brings about the destruction of a stolid middle-class household. It shares this basic story with an earlier Kim picture, 1960’s The Housemaid (하녀), which is now regarded, in the company of Yu Hyun-mok’s Aimless Bullet from the following year, as one of the greatest Korean films of all time. Restored by the Korean Film Archive in 2008, it was later granted the supreme cinephile imprimatur of an edition in the Criterion Collection. That the release came endorsed by Parasite director Bong Joon-ho, star of last year’s Academy Awards ceremony, speaks to Kim’s lasting influence on Korean cinema. More than 20 years after his death, he lays fair claim to the title of the most important Korean filmmaker of all time.

Though unreservedly melodramatic, The Housemaid exudes an elegance characteristic of South Korea’s “Golden Age” films of the 1960s. Among the many qualities attributed to Korean films of the subsequent decade, however, elegance seldom appears. Losing their audience to television and Hollywood while laboring under political censorship, some filmmakers spent the 1970s cranking out cheaply titillating “quota quickies” in shopworn genres. Kim, not apparently averse in any case to onscreen sex and violence, used these conditions to advance a genre all his own. 1977’s shamanistic nightmare Iodo (이어도) may well be his standout film of the period, but the core of the enterprise comprises Woman of Fire and his other subsequent remakes of The Housemaid, the picture that according to scholar Chris Berry had “established Kim as an auteur and a brand, with a certain set of obsessions that audiences expected him to manifest repeatedly.”

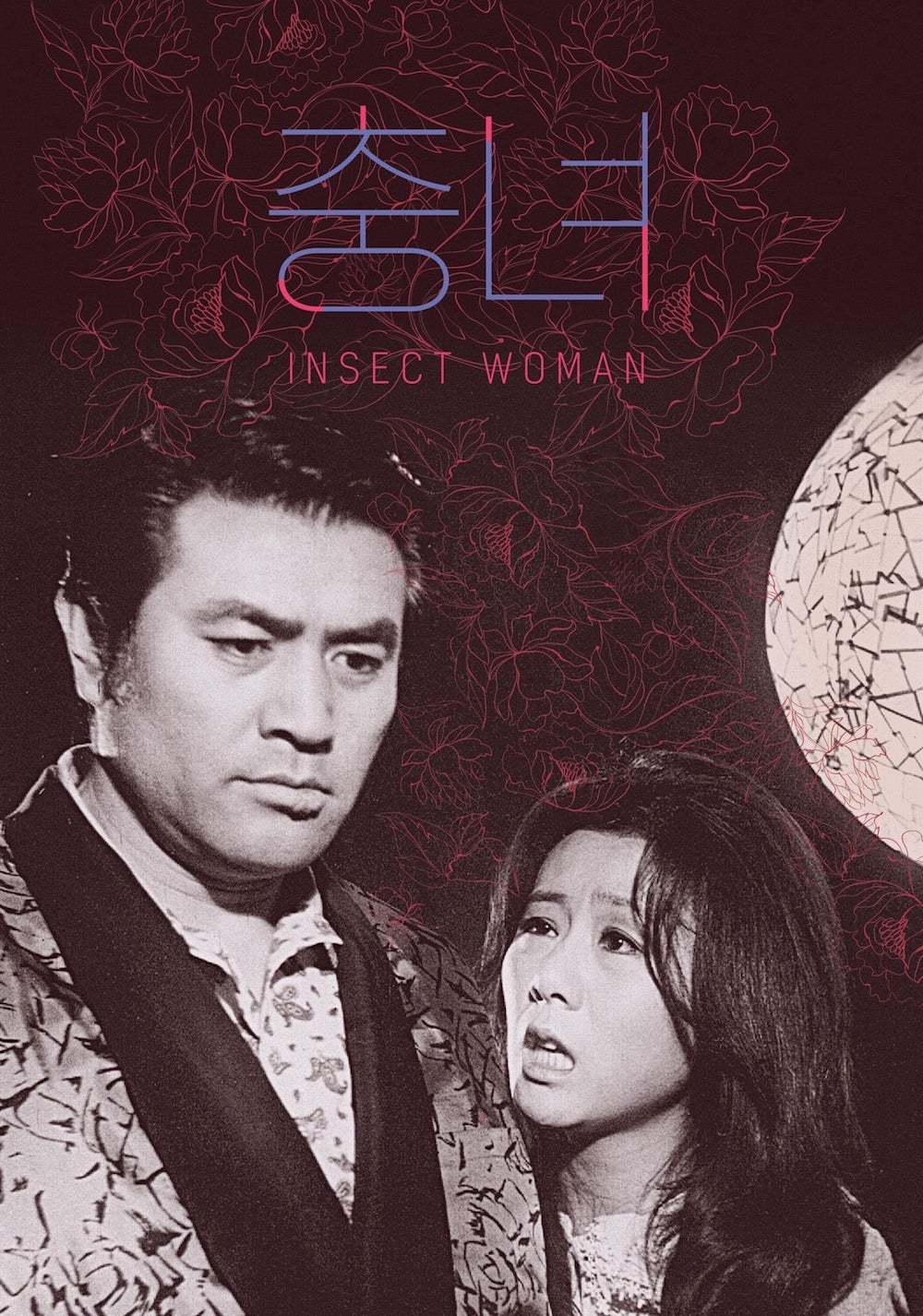

In the same essay, included in the reader Rediscovering Korean Cinema, Berry quotes Kim himself explaining these frequent remakes as an opportunity to “portray the changes in Korean society and the crisis of the bourgeois family every ten years.” But it only took him a year to follow up Woman of Fire, the Housemaid of 1971, with The Insect Woman (충녀), the Housemaid of 1972. In each films Youn plays a different young woman named Myeong-ja; in the latter, the death of Myeong-ja’s father forces her to go to work as a bar “hostess” paid to chat with and drink alongside favored members of its middle-aged clientele. Soon she becomes the mistress of Kim Dong-sik (also the name of the head of The Housemaid‘s household), a husband and father rendered impotent by the economically superior position of his wife, the heiress of a trucking company.

Taking notice of the reinvigoration her husband has undergone as a result of his liaison with the younger woman, Dong-sik’s vigilant wife goes so far as to explicitly permit their relationship. As long as Myeong-ja keeps Dong-shik in a robust health, as defined by certain parameters of weight and blood pressure, she will be allowed to keep him for half of each day. This is only one of the grotesque turns the film introduces into its story, carried over from The Housemaid and influenced by scandalous headlines of the time. When Myeong-ja starts getting ideas about having a baby, Dong-shik’s wife drugs him and hustles him into the hospital for a non-consensual vasectomy. Yet when Myeong-ja moves into a freshly built two-story home — paid for by Mrs. Kim — she discovers an abandoned infant in the refrigerator and decides to raise it as her own.

That isn’t the half of The Insect Woman, a movie better experienced than explained. In that sense it has something in common with the work of a Western director like David Lynch (made though it was years before Lynch’s feature debut), a comparison made even by Korean critics. Of its many scenes that leave an impression on the mind, perhaps the most memorable is the one shot through the bottom of a glass table covered in marble-like multicolored sweets, on top of which Myeong-ja and Dong-sik have uncomfortable-looking sex. By this point Myeong-ja has transformed from a defeated teenager into a full-fledged seductress, and one destined — as anyone familiar with the implacable moralism of Kim’s work will foresee — for a flamboyantly grim end. The story’s end, which leaves Myeong-ja no apparent option but murder-suicide, feels a long way indeed from the sensibility of the K-grandma.

But then nor is Youn’s character in Minari much like a grandma, as her grandson repeatedly observes. Just as Kim created his own genre, so Youn has created her own type. I’ve heard her style of performance likened to a hot pepper, both for its spiciness and clean astringency, and that strikes me as a fair description of her work for Hong Sangsoo, four of whose films she’s appeared in over the past decade. Though it wouldn’t be wrong to call most of the characters she’s played for Hong sexless busybodies — hardly an uncommon presence in Korean cinema — she somehow brings an unusual degree of both hardness and compassion to the roles. The same goes for her starring turn as an elderly prostitute-turned-mercy-killer in E J-yong’s The Bacchus Lady (죽여주는 여자), a spiritual successor of the women she played in the 1970s.

Far from having dedicated herself to such daring parts or idiosyncratic directors, Youn has participated in more than a few conventional film and television productions over the past couple of decades (including Im Sang-soo’s slick remake of The Housemaid from 2010). Whatever that kind of work has done to keep her a star in Korea, the success of Minari has made her all but inescapable: whether on television, the sides of Seoul buses, or tower-mounted video screens, she now seems to be under advertising contract to about a dozen different products at once. In the Korean entertainment industry, quite unlike the American one, appearing in commercials is the surest sign of having made it; by that standard, Youn must be one of the most successful performers in the country — 30 years after having been seen by some as a washed-up divorcée who used to star in tacky exploitation movies.

Admittedly, the print of The Insect Woman available for viewing on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel does look as if it’s spent the past 50 years circulating around the world’s grindhouses. But this delirious patina, combined with the luridness of the movie itself (though Kim’s subsequent updates Woman of Fire ’82 and Carnivore go to brazen extremes of their own) make for as rich a viewing experience, in its way, as the immaculately restored Housemaid. Some critics today, even those with an interest in Korean cinema, worry about how to regard such “outdated” films, not just in aesthetic sense but a moral one. They flinch from acknowledging that the human impulses — which is to say, the animal impulses — driving the likes of The Insect Woman have dated not at all. Kim surely knew they wouldn’t, which goes some way to making him a genius director by itself.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Bong Joon-ho’s Biggest Victory: Accepting His Oscars in Korean

Between Boring Heaven and Exciting Hell: Kim Soo-yong’s Night Journey

Let’s Get Out of Here: The Bitter Korean Neorealism of Yu Hyun-Mok’s Aimless Bullet

Korean Provocateur: the Harrowing Films of Kim Ki-duk (1960-2020)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.