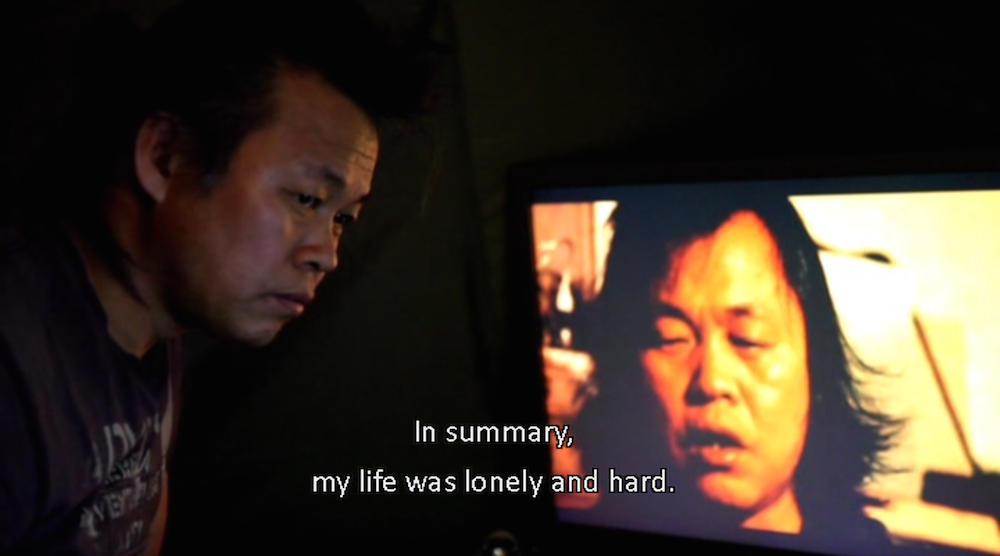

Kim Ki-duk died last month, and not for the first time. The coronavirus caused his death in reality, whereas his cinematic death occurred nearly a decade ago. It happened in Arirang (아리랑), a film Kim shot alone in a spartan countryside cabin to which he’d exiled himself for the previous three years. In it the filmmaker takes himself to task for his failure to maintain the productive momentum under which he’d directed internationally acclaimed pictures like Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (봄 여름 가을 겨울 그리고 봄) and 3-Iron (빈집). He attempts to explain his retreat — an actress was nearly killed on the set of 2008’s Dream (비몽), certain collaborators defected to the mainstream — but finally resorts to annihilation. Armed with a revolver crafted using his own machine tools, he drives into Seoul and apparently executes those who betrayed him before turning the homemade gun on himself.

This portrait of the artist as a self-pitying outcast does offer Kim the chance to tell a remarkable life story. Having never reached middle school in a society known for denying futures to those without prestigious tertiary education, he worked in junkyards and factories at a young age. After serving in the Marines, he studied theology for a time before redirecting his autodidactic energies to art, going so far as to spend a few years painting on the streets of Paris. There, in his 30s, he first set foot in a cinema, and would later credit screenings of Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs and Leos Carax’s Les Amants du Pont-Neuf with inspiring his dedication to film. Back in Korea he began writing a screenplay (having yet to attain full literacy, so the story goes) that would win an open contest held by the Korean Film Council in 1995.

Kim’s debut feature Crocodile (악어) came out the following year. Its scenes of destitution, prostitution, rape, murder, and suicide prefigured themes of his later work, and its eponymous character marks the first appearance of a recurring type: societally marginal, nearly mute, and subject to uncontrollable outbursts of violent rage. Despite not actually a being crocodile, Crocodile’s behavior is often indistinguishable from that of a dangerous wild animal. The same holds for the title figure in 2001’s Bad Guy (나쁜 남자), portrayed, like Crocodile, by Cho Jae-hyun, a frequent enough collaborator to be regarded as Kim’s onscreen avatar. This sexually frustrated small-time thug impulsively kisses a college girl he spots in a park, earning a righteous beating from a pack of soldiers drawn over by the ensuing commotion. In retaliation, he soon thereafter orchestrates her capture and effective sale to a brothel.

This is hardly the grimmest Kim’s cinematic vision gets. Address Unknown (수취인불명) takes place in the scraggly settlements around the United States Army base in remote Pyongtaek. Its milieu includes a schoolgirl with one clouded-over eye, a young man (Kim’s real-life childhood best friend) ostracized for his half-black parentage, dealers in kidnapped local dogs destined for the stewpot, and a G.I. who can’t get through the day without popping a few tabs of LSD. I do sense some measure of humor in that odd choice of drug (serving a narrative purpose though it does in this land of precious few non-alcoholic mind-altering substances), as well as in some of the events Kim stages in this bleak setting, as when a main character ends up thrown from his motorcycle head-first into a paddy, his legs left sticking out aboveground like a grave marker.

Nearly 20 years have passed since Address Unknown and Bad Guy, of course, and twenty years of change at a Korean pace. While the absolute amount of prostitution in Seoul probably hasn’t fallen by much, the city’s most visible red-light districts have been redeveloped; no longer do girls call out to passerby from open storefronts. Though the U.S. Army remains in Pyongtaek, it’s surely also changed the place’s character over the past couple of decades, having greatly expanded its facilities there while reducing its presence in the capital. Making his pictures of the late 1990s and early 2000s, Kim captured a palpably different Korea from the one in which I arrived half a decade ago, a country somehow both drab and garish at once and utterly awash with sin — a depiction with which Kim no doubt took his liberties, though fewer, I suspect, than it may seem today.

Yet in some sense I do live in Kim’s Korea, his films having done much to form my mental image of the country and its society years before I arrived. The Korean Film Council brought Kim out of obscurity with its screenwriting prize, and it also brought him to my attention with the DVDs it distributed to such foreign institutions as my university’s media library. There I happened upon 3-Iron, a film that deepened my fascination with the many ways, both subtle and unsubtle, in which the cultural image projected by Korea differed from not just that of the United States, but even more strikingly from those of the other Asian countries of my cinematic acquaintance. Its Korean title (which I could barely read at the time) means “empty house,” and it was through those empty houses that the distinctiveness of Korea so memorably presented itself to me.

3-Iron‘s protagonist Tae-suk is a young laborer tasked with riding his motorcycle around Seoul and sticking restaurant delivery menus onto every front door he can approach (a fixture of daily life to which I’ve grown accustomed in my years here). Though presumably not well-compensated, the job suits his lifestyle: taking notice of which fliers fail to disappear from their doors, he breaks into each unoccupied home and lives there for a few days, helping himself to a home-cooked meal or two and washing the residents’ clothes in seeming compensation. These passages of the film constitute a kind of record of the various environments in which Seoulites lived in the early 2000s, most of them modest, some fairly luxurious, and all of them new to me: never before had I seen hanok, for example, the kind of traditional wooden courtyard houses today owned almost exclusively by the well-off.

Nor was I familiar with the standard middle-class Korean home and its accoutrements: the enclosed balcony and laundry rack, the child’s “study desk” with its shelves full of workbooks, the oversized studio portrait of the family, images of a beatific, light-skinned Jesus. After one such residence Tae-suk moves up a socioeconomic rung or two, finding his way somewhere grander and more secluded, practically a mansion by comparison, its grounds outfitted (bizarrely, as I first saw it) with Italianate sculptures and a miniature driving range. This one turns out not to be empty: by the time this least talkative of Kim’s heroes comes face-to-face with Sun-hwa, the equally silent lady of the house, she’s been watching him make himself at home for some time. With her black eye and split lip — presumably inflicted by her volatile, polo-shirted husband — she resembles a ghost, and indeed may be one.

Kim acknowledged an interpretation of 3-Iron that casts Sun-hwa as a figment of Tae-suk’s imagination, as well as one that casts Tae-suk as a figment of Sun-hwa’s imagination. Either way, or neither, Tae-suk masters a discipline Kim called “ghost practice,” which allows him to escape his eventual imprisonment and re-enter Sun-hwa’s daily life while remaining entirely unseen by her husband. The movie won Kim the Venice Film Festival’s Silver Lion for Best Direction in 2004, a period in which the director departed from his initial realism, grotesque and occasionally comical through it was, for for more conceptual scenarios in which some viewers saw a spiritual dimension. This was especially true of European viewers, who earlier that same year had enthusiastically received Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring, the spare story of a Buddhist monk and his young disciple resident in a small temple floating in the middle of a lake.

Brazenly placid in comparison to Kim’s previous films (as well as many of his later ones), Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring includes no prostitutes, drug use, or dog stew. It does manage to incorporate suicide, albeit ritual suicide, as well as sex and murder — though unlike its immediate predecessor The Coast Guard (해안선), not simultaneously. Watched in the context of Kim’s entire filmography, which I’ve been revisiting since his death, it plays in its relative gentleness almost like an atonement for 2000’s The Isle (섬), which is also set amid otherworldly floating buildings. In that film Kim creates another character of few words and many bestial acts: a woman, unusually, the owner of a fishing resort who delivers working girls to her customers but makes intimate demands of her own on a criminal who comes to hide out from the law.

The Isle makes for viewing as harrowing today as it seems to have been in its early screenings, which produced reports of fainting and vomiting in the audiences. Whether those reactions were provoked by the scenes of real violence (the live skinning of a frog, for example) or simulated violence (more than one attempted suicide by fish hook) I’m not sure, but the picture in any case did more than its part to forge an association between Korean cinema and the idea of “extreme Asia” abroad in those days. Looking back, one might wonder about the possibility of Kim’s having actively played into Western notions of east Asian film, despite his studied self-presentation as an aesthetic and intellectual outsider. From the appearance of Buddhistic rigor and serenity he moved on to a series of pictures dealing with societal alienation, often involving sexual relationships of a strange or brutal nature.

Up until the crisis of confidence induced by Dream, the last of those pictures, Kim arguably remained the face of Korean cinema in the West. Despite the prizes and acclaim lavished on his films at foreign festivals, however, he never found a wide audience in his homeland. The irony was not lost on him: in Arirang he mentions being rewarded by the state for ostensibly representing Korea, but “if you look closely at my films,” he adds in a considerable understatement, “there could be things that embarrass the country.” Nevertheless, he also expresses a desire to make the first Korean picture to win a grand prize at a major film festival (“I’m human, after all”) which he would do with the following year with Pietà (피에타), a religiously charged psychosexual nightmare — and for Kim, a cinematic rebirth — that took the Golden Lion at Venice.

European film festivals know an auteur when they see one. Venice has also proven a friendly venue for the films of Hong Sangsoo, another Korean filmmaker more popular abroad than at home. So have Cannes and Berlin, where Hong won the Silver Bear for Best Director for last year’s The Woman Who Ran. Bong Joon-ho got the Palme d’Or for Parasite, of course, muted though that news was by the picture’s subsequent dominance of the Academy Awards. This marks a definite changing of the guard; the era when the likes of Kim Ki-duk could stand for Korea in world film culture has well and truly come to an end. A country could do worse than to produce a director like Bong, possessed as he is of the rare combination of crowd-pleasing instincts and superhuman attention to detail. But that’s something quite different than an obsessive, near-savage drive to create.

Pietà would be Kim’s final victory as a filmmaker. Apparently seeing no option but to exercise his proven tendencies more intensely, he followed it up with the dialogue-free Moebius (뫼비우스), which features an incestuous castration scene daring even by the standards of incestuous castration scenes. The film played a part in his eventual undoing, though not because of its content: some time later, an actress involved early in its shooting publicly claimed that Kim physically struck her and pressured her into an unplanned sex scene. These and other accusations made during what’s been called “Korea’s #MeToo moment” brought Kim (as well as his “persona” Cho Jae-hyun) low, though cinephiles had been remarking for several years on his apparent artistic decline. His last few films mostly failed even to gain wide distribution — a mercy, perhaps, given their thematic heavy-handedness and often shockingly low production values.

And yet. “My dream is to live in various countries and make films there,” Kim declares in Arirang, and whatever the ignominies of his late period, it saw him beginning to live that dream. Having returned to Paris for two different shoots, he made films in Japan and Kazakhstan in the years before he died in Latvia, not an entirely unsuitable resting place for an artist respected primarily in Europe. And despite the recent scramble to strip him of whatever “genius” status he had — the declarations of “I never cared for his work” begun anew with his obituaries — he was indeed an artist, at least to those of us who don’t reject art by taking offense at its subject matter or the conduct of its creators. Among those who do, few must be sorry to see Kim Ki-duk gone, but they can never wish his films away.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Revisiting 301, 302, Park Chul-soo’s Stylish Film About Food, Sex, and Other Horrors

The #MeToo-ing of Ko Un, Korea’s Best Hope for a Nobel Prize

The Woman Who Ran: The Cinematic-Romantic Collaboration of Hong Sangsoo and Kim Min-Hee Evolves

The Making of a Korean Monster: Kim Sagwa’s Bloody High-School Novel Mina

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.