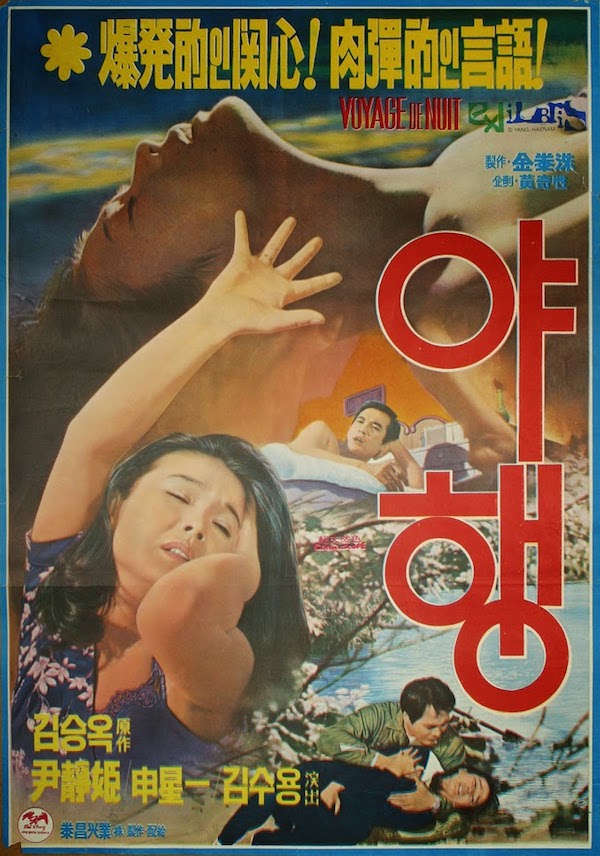

This is the first in a series of essays on the important pieces of Korean cinema freely available on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel. You can watch it here.

By day, Miss Lee and Mr. Pak work at the same bank in downtown Seoul, maintaining an ostensibly cordial if chilly professional relationship. But at night, they both return to the same apartment in a riverside tower block, where they live almost — but not quite — as husband and wife. “Weddings are lame,” insists Mr. Pak when Miss Lee, spurred by the coming nuptials of another formerly secret office couple, asks if they’ll ever have one of their own. He then nods off, putting an end to one of their rare opportunities to communicate, hemmed in as they are by the need for propriety at work and the insistence of his superiors at the bank on round after round of nightly drinking.

Having reached her late twenties without any marriage prospects, at least as far as the rest of her colleagues know, Miss Lee, given name Hyeon-joo, plays the role of the office “old miss” (올드미스), a title she’d until recently shared with the worker who sits next to her, the one about to get married. The boss, apparently out of pity, gives Hyeon-joo some time off and a holiday bonus as well, which Mr. Pak, in his work persona, jokingly suggests she use to tag along on the newlyweds’ honeymoon. Humiliated, she must wait until the evening at home before she can scream, shout, and throw household objects as well as punches in retaliation at her husband-to-be-or-not-to-be.

This domestic battle cuts straight to a televised boxing match, which the couple watches in rapt, half-drunken excitement. When a round ends and the broadcast cuts to commercial, they fall amorously to the carpet, but they’ve barely got started before the fight resumes and Mr. Pak snaps back to attention, chanting and punching along with this geopolitically charged contest between a Korean boxer and a Japanese. Hyeon-joo remains sprawled on the floor, and we get a long look at her disappointed expression, a mixture of shock and bitter expectation at her apparent inability to compete with the flickering entertainment. How, she wordlessly says, can it have come to this?

The malaise of modern marriage — or modern quasi-marriage, anyway — has provided a reliable (and perhaps too reliable) theme in the fictions of many societies for decades and decades. Usually these stories end with either a union dissolved or made stronger than ever, but Kim Soo-yong’s Night Journey (야행) departs from the tradition by ending with Mr. Pak and Hyeon-joo’s relationship in the essentially tentative state in which it began, but sending the latter on a haunting, erotically charged odyssey in the meantime. Stanley Kubrick would do the same thing a quarter-century later in Eyes Wide Shut, but he did it to a man in 1990s Manhattan, which makes a fairly different statement than doing to to a woman in the South Korea of the 1970s.

Kubrick, who got most of his material from novels, adapted Eyes Wide Shut from Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle (or “Dream Story”). Kim, whose prolific filmmaking career has also tended toward literary adaptation, took the material for Night Journey from a short story by Kim Seungok, a writer who, in a burst of creativity during the 1960s, produced a body of nihilistic work that crystallized his generation’s experience coming of age in a country careening toward a state of both full industrialization and harsh repression. His best-known story, “Seoul, Winter, 1964” (서울, 1964년 겨울) showcases the author’s thorough knowledge of the city as well as his thorough knowledge of what it feels like to lead a meaningless life within it.

Hyeon-joo decides to use her holiday time and money on a solo trip out to her small coastal hometown. There she immediately changes into her old high-school uniform and relives her youth, taking her little sister bicycling along the beach as she was once taken by her first love, a teacher who, not long after consummating the relationship, went and got himself killed in Vietnam. All that had the Korean-seaside-hamlet rumor mill going full tilt, forcing Hyeon-joo to leave home for Seoul, but now, back in town, she draws the attention of a widowed former acquaintance, the scion of a local factory-owning family. But despite his habit of going around on a roaring motorbike in a white leather cap and aviator sunglasses, he proves more timid than the brutish playboy for whom she’s found herself hoping.

Kim Seungok’s original story focuses on this compulsion. Its Hyeon-joo spends night after night wandering the streets of Seoul, longing for passers-by to fix on her as an object of desire — the more roughly handled an object, to her mind, the better. The film’s Heyon-joo does share her textual counterpart’s taste for being grabbed by the wrist (even drawing a fetishistic charge from the sight of handcuffs) and taken to the nearest yeogwan (여관), a kind of cheap, old-fashioned hotel, but she spends the rest of her vacation after returning from her hometown in search of viscerally cathartic experiences in general.

Visiting a café that overlooks her and Mr. Pak’s workplace, she casts a glance across the room at a rough-looking fellow sitting alone, and in her imagination entertains a brief fantasy of the two of them as a kind of Korean Bonnie and Clyde, dapper in dress and with guns blazing. (In reality, he skips out on his bill, leaving Hyeon-joo to pay it.) She goes to an arcade, giving its punching bag hell as the prepubescent clientele looks on in a kind of amused pity. As she re-emerges onto the streets and the night darkens further still, increasingly unsteady men circle around her, asking for a light, asking for a drink, asking for a dance.

That last one turns out to be one of the boys from the bank — the very same one, in fact, whose wedding to the other “old miss” she’d attended just days before. “You must be enjoying your honeymoon,” Hyeon-joo says to him. “I did not enjoy my honeymoon,” he replies. “She wasn’t a virgin. Virgins, where have you flown off too?” His frustration, which has by now reached a theatrical pitch, peters out: “Men are all the same. We don’t like anything complicated. There are no virgins in this world anyway.” He might just as well have asked where everything else about the world he knew growing up, or thought he knew about the world growing up, had flown off to.

These characters make their way through what must have looked like a startlingly modern city in 1973, but the film presents the fast developing Seoul as a highly anomic kind of place, its inhabitants — even the basically middle-class ones like Hyeon-joo and Mr. Park, who look out from the balcony of their high-rise at the balconies of another high-rise — racked with feelings of dislocation. And to make matters worse, as Hyeon-joo finds (though she finds it more dramatically in Kim Seungok’s story, which has the tearfully reunited mother and daughter plunging into mutual spite in a matter of days), you can’t go home again. The men get caught in the samsara of eighty-hour work weeks and the regimented bacchanalia that goes with them, and as for the women, who knows what they’re liable to do in their desperation to feel something?

The Koreans have a saying about how you choose either a boring heaven or an exciting hell. It can apply in a variety of contexts, but I most often hear it used to describe the choice between emigrating to the West, the boring heaven, or staying in Korea, the exciting hell. Kim Soo-yong, whose style critics describe as a bridge between traditionalism and modernism, renders an exciting hell indeed — or, to put it in terms more suited to the medium, a vivid nightmare, rendered in the somehow muddily rich colors of the era (1970s Korea didn’t dodge that flood of orange, green, and brown any more than 1970s America did) as well as its cinematic techniques: freeze frames, dubbed voices speaking with dreamlike clarity, an ominous score that generates uneasiness still through incongruity, and an unexplicit, metaphor-intensive eroticism. (The director gets plenty of mileage here out of his signature image of waves splashing against the shore.)

But even such hellish excitement can consign the Hyeon-joos of the world to a deeper, more existential boredom, and the Kim would return to the theme of a woman’s consequently compulsive self-ejection from the rigors of Korean life in his next film A Splendid Outing (화려한 외출), the story of a high-powered Seoul entrepreneur who, overtaken by the desire to drive to a sea village she’s seen in a dream, finds herself sold as a wife to an island fisherman. It, too, stars Yoon Jeong-hee, best known in recent years for her comeback performance as an Alzheimer’s-afflicted grandmother in Lee Chang-dong’s Poetry (시).

A Splendid Outing came out almost at the same time Night Journey which, while shot in 1973, couldn’t get past the censors until 1977. Though Kim has claimed they made substantial cuts, it still comes off as much more daring a movie than one imagines emerging from its time and place. Even today, outsiders perceive South Korea as a conservative, buttoned-up, almost martial society, but behind that veil of conservatism people more or less obey their impulses. Kim’s films show, captivatingly, how new a condition that isn’t.

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.