By Colin Marshall

This is one in a series of essays on important pieces of Korean cinema freely available on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel. You can watch this month’s movie here and find links to previously featured movies below.

If you want to go see a movie in Seoul, you might well go to Wangsimni. Right above the neighborhood’s station on the central circular subway line stands a high-rise shopping complex whose multiplex theater boasts the largest IMAX screen in the country. It went up less than a decade ago, in 2008, but Seoul changes quickly. This has held true at least since the end of the devastating Korean War, when the capital of the new state of South Korea had nothing to do but develop. Still, Seoul remained in fairly rough shape a decade later, in the early 1960s, the time in which the protagonist of 1976’s Wangsimni, My Hometown (왕십리) last saw his homeland.

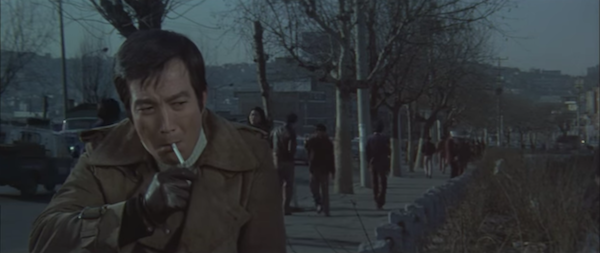

The disoriented but stylishly dressed Joon-tae first appears onscreen in a once deeply familiar Seoul, made strange in just fourteen years. As he struggles to place himself through the window of a cab, the driver asks what he’s looking for. “I don’t see the trolley,” says Joon-tae. “It’s been at least ten years since they got rid of the trolley,” the driver tells him. Joon-tae asks about another railcar he used to ride in his youth. “Trolley, railcar… that’s all history.” An Angeleno in the same era and in the same situation would have had the same conversation. Where did all the streetcars of the far-reaching Pacific Electric and Los Angeles Railways go?

Their disappearance looked dramatic enough to convince some of a conspiracy, but larger processes had converged to turn the city into something other than it had been before. Just as Los Angeles discarded the trappings of the late 19th and early 20th century it spent as a booming, barely-tamed settlement (and, to an extent, giant real-estate hustle) on the edge of the continent, Seoul discarded the trappings of the late 19th and early 20th century it spent as a subject of the Japanese empire. But that mid-1970s Angeleno riding back into town might also wonder about something else: where did all these Koreans come from?

Though immigration from South Korea to Los Angeles began around 1900, it didn’t start happening in enough force to affect the character of the city until the exodus resulting from the Korean War and, a little over a decade later, the passage of the restriction-loosening Hart-Cellar act of 1965. The Koreans who came to America up until that time left a homeland still partially in ruins, and many never updated their mental image of the place. In her story collection Drifting House, Krys Lee writes of one such immigrant, who “had watched Korean news clips of the developing country’s daily disasters — student demonstrators attacked by pepper-spray bombs in 1986, the Sampoong Department Store collapse that killed generations of families in 1995 — and convinced himself that he had been right to leave.”

Of those former Seoulites who convinced themselves of their rightness in leaving — even, as Lee puts it, “after the country flourished and began giving academic scholarships to the brightest from Guatemala to Mongolia, and setting trends in film and technology” — the ones who return today, even just to visit, find the city utterly transformed. The trolley and railcar never came back, but Seoul, safe to say, doesn’t need them now that it has perhaps the world’s finest subway system, while even Los Angeles still struggles to build out its own.

To be fair, the Seoul Metro had a bit of a head start on the Los Angeles Metro, opening its first line in 1974 rather than 1990. Two years later, it hadn’t yet reached Wangsimni, which thus remained in enough of an urban isolation to qualify more as a true “hometown” (고향) than as just the old neighborhood. It also retained its now long-gone rough-and-tumble image, exhibited — and insisted upon — by the remains of Joon-tae’s old crew. Checking into a cheap hotel, he begins seeking them out by heading straight to the local pool hall, the hangout of choice for every Korean man of a certain generation, finding both the establishment and its owner in a diminished state.

The hall has shrunk from two floors to one, and the man, Choi, rendered nearly unintelligible (at least to my foreign ears) by ancient slang and drink, bursts every so often into intense despondency about his lack of progress in life. Joon-tae, too, sees himself as having stood shamefully still for the last fourteen years. He left Korea suddenly in order to avoid an epic inheritance dispute, his tearful fiancée chasing futilely after his departing taxi. Though the intervening time apparently saw him make quite a name for himself, as well as a small fortune, as some kind of valuable operative in the Japanese underworld, he returned just as suddenly, bringing his cashed-out savings with him and claiming to have come for one reason only: to see Jeong-hui, the girl he left behind, one last time.

But before he can get to Jeong-hui, another woman comes his way: Yoon-ae, a prostitute sent to his room by Choi and the rest of his buddies. Instantly enamored by Joon-tae’s distance, disinterest, and apparent inability to take care of himself, she goes from washing his clothes (for which he reprimands her) to inviting him over and cooking dinner (an appointment he forgets, or simply disregards) to proposing marriage, all in a matter of days. And as the whore tries to turn Madonna, the Madonna seems to have endured deeper reversals of fortune: while Joon-tae at first hears, and hopes, that Jeong-hui has married well and now lives comfortably, he comes to find out that she’s actually fallen to the status of “the biggest floozy in Wangsimni.”

Joon-tae nevertheless feels honor-bound to do right by Jeong-hui, going so far as to take out an ad in the newspaper to find her and, when he does, to buy her a new, Western-style house in cash. He does so in front of an infuriated Yoon-ae, who’d taken him for a fellow lost soul but now, having found out about his money, demands a few gifts of her own. Later, sitting amid the almost parodically 1970s décor of one of the many coffee shops that proliferated in Seoul in that era, she rejects the finery he’s just bought her and, before storming out, tells him off: “You made me think a girl like me can get married. You made me have hope. Do you know how? You looked like someone who could need me.”

But our laconic antihero has bigger problems: all throughout the film, a minder name Sasaki has tailed him through the city, trying to hasten his return in order to secure his participation in a mob war about to erupt back in Japan. Despite at first having vowed to make this trip the last time he would ever set foot in Korea, his resolve seems to waver as the complications of his situation mount. The more he learns of Jeong-hui’s current situation, the less she seems like an innocent victim of circumstances — and the more appealing Yoon-ae’s proposition becomes. Maybe, he starts to think, he can take her back to Japan with him.

Korean stories, though, have never let their characters execute their plans or satisfy their desires as simply as that. He catches Yoon-ae already on her way back to the farm village she calls her own home town, planning — doomedly, one senses — to lie her way into marriage to a childhood friend. The movie ends on New Year’s Day, with Joon-tae chased through a lumber yard by a team of enforcers assembled to bring him back at any cost. “I decided to stay,” he explains to Sasaki and his glowering, advancing henchmen. “I just realized that this is where I belong.” Just then, Choi and the rest of the fellows with whom he presumably belongs with rush up to defend their friend. The Japanese gangsters fell them easily, but Joon-tae, turned into a fighting machine by a presumable burst of hometown pride, in turn fells the distracted Japanese gangsters even more easily.

“I’ve been living all these years not caring about anything,” Joon-tae admits to Choi as they stand on a stone bridge overlooking some watery land surely soon to be developed and redeveloped. His closing monologue convinces them both to finally “lay down some roots” in the Korea that threatens to pass them even further by. “Everyone’s busy living their lives, while the two of us circle around the same spot not knowing what to do. We’re the only two who haven’t been able to really live our lives. Let’s on our lives from now on. This is our home. Why do we live like we’re just passing through? We’ve got to find our lost fourteen years and make up for lost time. Let’s make wings. With those wings, let’s fly in the sky.” The two old friends then nearly double up in non-ironic laughter.

A free-floating modern Westerner could find this stirring indeed, revealing as it does parts of the Korean sensibility that entices many expatriates to stay: the refreshingly unquestioned emotion, the nigh-unbreakable bonds of friendship, the sense of a country and culture as collective enterprise. But that sort of thing also puts off its fair share of Koreans — including, for a time, director Im Kwon-taek. A teenager at the time of the Korean War and later vilified as the son of a communist, he saw firsthand how a society can tear itself apart. He effectively turned his back on his homeland, becoming a self-described thoughtless journeyman filmmaker known in the industry for his ability to near-continuously crank out cheap, commercial genre pictures.

The effects of Im’s awakening manifest gradually over the course of his work in the mid-1970s. Wangshimni came out in a year when he made at least three other pictures, none of which contain the kind of declaration of self he put into the mouth of Joon-tae. Over the following decades, Im would transform from a pure hack into a maker of art-house films — and sometimes blockbuster-successful art-house films — that examine the Korean condition past and present. Revivre (화장), a dreamy drama of a tormented middle-aged cosmetics executive (played by Ahn Sungki, Man-su of Chil-su and Man–su) debuted in 2014 promoted as Im’s 102nd film, though given all the losses and rediscoveries made since he began his directorial career in 1962, nobody can be quite sure of the number.

None of us would want to subject ourselves to the societal forces that freighted Joon-tae and Choi, or indeed Im, with such apparent despair in the first place, but more recent generations of Koreans seem to have positioned themselves relative to Korea, whether inside or outside it, with less agony. When Tokyo-based American friend of mine recently visited Seoul, he caught up with some of the Koreans with whom he’d studied in Japan, all as international students, years ago. He expressed great admiration for their sentiments that, though they’d spent significant amounts of time living, working, and studying in other countries, they’d returned to Korea confident that they would, in the long term — or could, in the long term — make their homes nowhere else.

Declarations of that kind can, of course, smack as much of complacency as devotion. For all the fuss made here about producing “global challengers,” fewer Koreans have a genuine interest in hammering down stakes outside Korea than the nation’s image of internationalist dynamism make make it seem. (This goes especially for Korean men, with their notorious resistance to embrace things foreign in comparison with the country’s more xenophilic women.) And as much sincerity as Im’s more personal films of the Wangshimni period and after evince, he also made his artistic shift with a certain degree of strategy. The blockbuster era having just begun over in Hollywood, he knew the homegrown genre pictures of the day couldn’t compete with imported multimillion-dollar spectacles. Now, of course, Korea makes its own multimillion-dollar (or rather, multibillion won) spectacles of its own, which screen right alongside the American ones. If you don’t believe me, catch a train to Wangsimni and see for yourself.

Related Korea Blog Posts:

Watching Madame Freedom, the Movie that Scandalized Postwar Korea

The Unbearable Preposterousness of Westernization: Park Kwang-su’s Chil-su and Man-su

Between Boring Heaven and Exciting Hell: Kim Soo-yong’s Night Journey

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.