This is one in a series of essays on important pieces of Korean cinema freely available on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel. You can watch this month’s movie here. Last month’s movie was Kim Soo-yong’s Night Journey (1975).

Chil-su and Man-su (칠수와 만수) opens with an air raid drill, a regular occurrence in the life of postwar Seoul even after the country turned from military dictatorship to ostensible democracy in 1987. The movie came out the following year, when modern South Korea made its debut on the world stage by hosting the 1988 Summer Olympics. Korea-inexperienced Westerners who came to watch the games, especially Americans primed by episodes of M*A*S*H, found, by most accounts, a more developed, more orderly, and — why mince words — more Westernized country than they’d expected. But even those who left having bought the narrative of the phoenix risen from the ashes could glimpse another story playing out on the margins of the scene, that of those barely touched, let alone elevated, by the economic Miracle on the Han River.

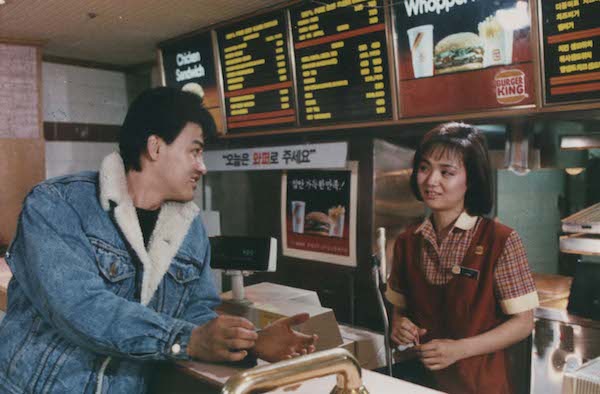

Park Kwang-su took two of the players in that other story and made them the title characters of his directorial debut. Chil-su, a 22-year-old dreamer employed as a theater movie-poster painter (very much a developing-world industry, though one still just barely alive in the late 1980s), quits his job in a fit of righteous rage against his stingy, hostile boss, declaring that he shouldn’t have to take his abuse in a democratic nation. Even more strapped for cash than usual and eager to woo a girl for whom he’s fallen after spotting her working at Burger King, he talks his way into a partnership with Man-su, an older sign-painter who at first treats him dismissively but to whom he nevertheless looks up.

And so, on one level, we have a comedy of two working-class guys trying to make it in the big city, but with an undercurrent of darkness that deepens as the story plays out. The jovial Chil-su lies compulsively: he tells everyone who will listen of his wholly fabricated plan to emigrate to Miami Beach and join his nonexistent brother and lets the object of his affection, whom he sketches at work while nursing a single Coca-Cola, believe that he attends art school. He does have a sister, but she vanished after their father threw her out of the house for consorting with American soldiers. The father himself remains in the family hometown, remarried after the death of Chil-su’s mother and slowly, bitterly pickling himself in soju.

Man-su, too, has gone in for a similar regimen of self-medication, drinking away days and nights without work. His own father has spent 27 years and counting in jail, a communist sympathizer incarcerated by a state driven nearly to insanity by its own anti-communist paranoia. Though without any communist leanings himself, Man-su had his application for a passport denied, and thus his own ambitions to go abroad thwarted, due to the perceived sins of the father. And so, despite his education, he must eke out a living painting advertisements for the new goods he can’t afford to buy and the high-rises he can’t afford to live in, retreating at night to the local roadside tent pub for some cheap liquor and maybe a drunken brawl or two.

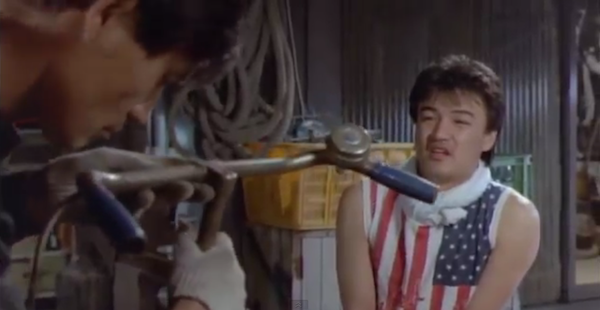

This all might seem punishingly grim if not for the sharpness of the film’s satire. Some of these satirical moments target the inequality the film presents as having deepened with Korea’s development. But the funniest moments of satire lampoon the country’s concurrent Westernization, and to certain generations of South Koreans, only one Western country matters: the United States of America. Hence not just Man-su’s groundless boasting about his imminent departure for Miami, but his attire: he first appears clad entirely in denim, and later — lest that outfit look only ambiguously American — in a shirt made out of the Stars and Stripes.

Some of this act Chil-su puts on purely to impress the cashier he loves, employed as she is in an American fast-food business transplanted into Korean soil, and possessed of a name, Jin-ah, that sounds as Western as it does Korean. When he finally lands a coffee date with her, she has to cut it short to make it to her class at an English-language academy, at which point seemingly random Koreanized English words begin to litter their dialogue. The next day Chil-su rings Jin-ah up to ask for from a construction-site phone booth, reading his English lines phonetically off a notecard: “How are you, hm? This is Chil-su Jang! I’m telephone you in the campus. You know? Here. And I wanna see you tomorrow again, okay?”

Their second date takes them to the movies — not, of course, to see a Korean film, but an American one, and not just any American film, but the ultrapatriotic Rocky IV. Watching Chil-su try to get his arm around Jin-ah during James Brown’s extravagant ringside performance of “Living in America”, I began to understand why North Korea refers to this part of the peninsula not as the South Korean side of the border but the American side. That’s not to say that, in Chil-su and Man-su‘s Korea, other countries — that is, other rich Western countries — don’t also merit imitation. In order to shore up his supposed identity as an art-school student, Chil-su arranges to take Jin-ah to an art gallery and “bump into” Mansu, posing with a pipe and beret as one of his former upperclassmen, just back from years in Paris becoming a famous painter.

That night, Chil-su, Man-su, Jin-ah, and one of her school friends end up at a club whose sound system pumps out, naturally, nothing but English-language pop music (including but not limited to Rick Astley’s immortal “Never Gonna Give You Up”). Man-su, deep in the cups and miserable in his pseudo-Parisian getup, stays seated when Chil-su and the girls hit the dance floor, and upon their return demands a bottle of soju. Embarrassed by this rustic choice of beverage, Chil-su tries to explain it away as the effect of not having had soju while abroad, but then Jin-ah’s friend suggests, instead, some “euiseuki on deo rak” — whisky on the rocks. This infuriates Man-su, who, dragged out of the club by Chil-su, delivers the saddest line of the movie: a plea to go out for soju and sea snails when they get outside.

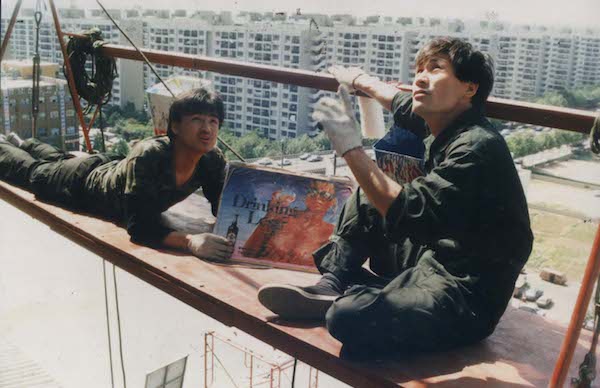

Chil-su and Man-su‘s famous final scene plays out high atop a building in Gangnam, Seoul’s wealthy southern half that suddenly went vertical in the 1970s, where our boys have just finished painting an enormous rooftop ad for, yes, whisky — and a whisky promoted with the image of a bikini’d blonde at that, emblazoned with the English words “Drinking less? Then drink better.” (The point, the executive commissioning the job says, is to be sexy, shoehorning in not just the English word for sexy but point as well.) Fed up with their lot in life, Chil-su and Man-su launch into a final catharsis by standing atop the sign and shouting denunciations of Korea’s wealthy, educated, and privileged at the countless freshly built tower blocks of Gangnam below.

Their harangue draws a traffic-stopping crowd. Unable to make out their words, onlookers assume the two are either putting on some sort of labor-related protest or about to leap to their deaths. Someone mistakes their after-work bottle of soju for a molotov cocktail, and before long the police, fire department, news crews, and even army have shown up. A bullhorn-wielding negotiator asks why they’ve given up on life, why they’ve disrupted society, and what their employers have done to cause this behavior, but Chilsu and Mansu, as ever, can’t make themselves heard.

The Korea-based American film critic Darcy Paquet calls Chil-su and Man-su “the first film that really did step in after the relaxation of censorship and make a political point. It’s somewhat indirectly stated. Westerners watching the film will not be shocked by its radicalism, but within the context of its time, it was a film that stood out.” He teaches this final sequence to his students of Korean cinema history, pointing out how it captures the ironies of the immediate post-dictatorship years, when “the working class tries to express itself, but there’s such a huge gap between them and the rest of society that misunderstandings are inevitable and conflict results.”

And though “certain aspects of Korea have changed quite a bit, other aspects have not. In many ways, the film industry has abandoned this type of filmmaking, but outside, there’s still a lot in today’s Korea that resonates quite strongly with what you see in that film.” Sometimes, despite the dramatic changes since then, I do feel as if I’m living in Chil-su and Man-su‘s Korea. Some of it has to do with the movie’s indictment of internal class issues; as I make my way past the circles of middle-aged drunks gathered on the concrete outside Seoul Station, some noisily airing their grievances and others simply passed out, I do wonder how many were the real Chil-sus and Man-sus of thirty years ago.

But most of it has to do with the movie’s indictment of a society so bent on development itself that it can’t spare a moment to think about know which way to develop, and so has often fallen back on embarrassingly direct replication of whichever countries it sees as more advanced. This manifests most humorously in Chil-su’s American flag shirt, Man-su’s pipe and beret, and Jina’s Burger King visor, but all the jeans, hooded sweatshirts, and Western business suits worn in the other scenes make just the same point, bringing to mind the questions I always have about the assumed “English” names with which Koreans introduce themselves to me with dispiriting frequency (and which they often have trouble pronouncing themselves): what on Earth does this have to do with you you are? What does it have to do with where you come from? Or does it only matter where it looks like you’re going?

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook. If you’re in town, come to the free, bilingual Seoul Book and Culture Club event he’ll host on Saturday, April 2nd, a conversation with award-winning young Korean writers Kim Ae-ran, Chan Kangmyoung, and Kim Min-jung.