This is one in a series of essays on important works of Korean cinema available free to watch on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel. Previous selections include Deep Blue Night, Aimless Bullet, Iodo, 301, 302, The March of Fools, Seopyeonje, Wangsimni, My Hometown, Madame Freedom, Chil-su and Man-su, and Night Journey. You can watch Yeong-Ja’s Heydays here.

Watch enough Korean movies from the late 1950s through the 80s, and you start to notice what looks like an obsession with prostitution. Pictures from the end of that period — 1988’s Prostitution (매춘), for instance, which has spawned at least five sequels — tend to make it obvious. Earlier ones deal explicitly with prostitution as a theme less often than they tell stories naturally involving prostitutes. In many cases their characters come from the ranks of the so-called “Western princesses,” the working girls of the Korean War’s aftermath whose clientele consisted exclusively of American servicemen. With their uncertain American-style names and American-style dress, they project a combination of abjectness and shrewdness — a distinct shame accompanied by a slightly higher-than-average level of material comfort — in which Korean filmmakers once found a useful symbol of their country and its relationship to the United States.

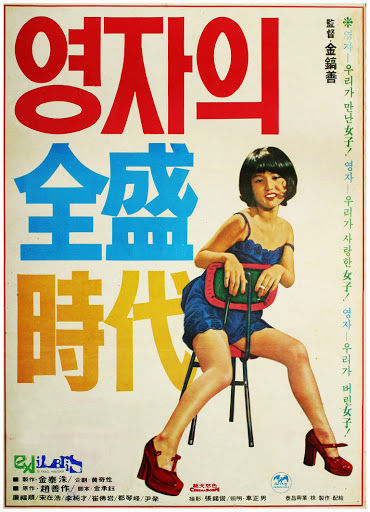

As the movies show it, South Korea changed dramatically in each of the five or six decades following the war, and most of these transformative eras produced their own kind of cinematic prostitute. In the mid-1970s, when the time of the Western princess had passed, the best-known such figure was the title character of Yeong-ja’s Heydays (영자의 전성시대), who doesn’t enter the film in the profession. Or rather, she does — and in the middle of getting arrested in a raid at that — but within minutes we see her as she was before the fall, a nearly unrecognizable young maid fresh from the countryside working at the house of a factory owner. Shyly she greets a worker named Chang-soo, come to make a delivery to his boss; smitten, he resolves that night to make Yeong-ja his. But the wedding will have to wait, given his fast upcoming three-year tour of duty in the Vietnam War.

Service in Vietnam, as more recently depicted in Yoon Je-kyoon’s hit Ode to My Father (국제시장), wasn’t an unappealing option for able-bodied Korean men looking to earn US dollars. For that film’s everyman protagonist, the war is one stop on the semi-sentimental journey through South Korean history that eventually reunites him with his beloved, a Korean nurse he first meets in his time as a coal miner in Germany. For Chang-soo, it’s a prelude to another, more painful and ill-fated struggle: his campaign to win back the heart of Yeong-ja, who in the intervening three years has turned into the foul-mouthed, lip-licking lady of the night incarcerated at the beginning of the film. She’s also minus an arm, the result of a crash during her brief stint as as a bus conductor, one of her attempts to make a living after the factory owner’s wastrel son forces himself on her. (His mother, despite having harshly dressed him down for previous behavior, blames Yeong-ja and fires her on the spot.)

No scene in the film is more memorable than the loss of Yeong-ja’s arm, not because it’s excessively graphic but because it’s in some sense not graphic enough. Flat on the pavement, she watches her severed limb — which lets out not one drop of blood — fly not just away from her but straight upward, as if filled with helium. This surreal sight could have been meant as a hallucination, though nowhere else does the film make an obvious visual departure from reality. It could also have been the result of a prop not behaving as intended, a more likely explanation given the “quota quickie” ethos of Korean cinema at the time. By law, a film company could maintain its license to import profitable Hollywood movies only if it produced a certain number of Korean movies each year. In accordance with this incentive, domestic pictures were cranked out in quantity as cheaply as possible, and sometimes not even released.

Despite these inauspicious conditions, the Korean films of the 1970s that leave an impression at all leave lasting ones indeed. Kim Soo-yong’s Night Journey, Im Kwon-taek’s Wangsimni, My Hometown, and Kim Ki-Young’s Iodo have previously appeared here on the LARB Korea Blog for that reason, and with them Yeong-ja’s Heydays shares a vivid grimness intensified by its straitened production. That’s not to say that the film offers no moments of levity, though how many of them were met with laughter in 1975 is difficult to say. For her injury Yeong-ja receives compensation of 300,000 won: less than $250, but enough, according to her friend, to start up a beauty parlor. Instead Yeong-ja sends the entire sum back to her countryside hometown, tearfully dictating the enclosed letter to her arthritic mother and her young siblings Yeong-boon, Yeong-soon, Yeong-hee, Yeong-ok, and Yeong-hoon.

This now sounds like a parody of the kind of origins with which Korean cinema and literature long supplied its protagonists, innocents who leave their birthplaces to earn money in Seoul, little suspecting how the big city will strip them of their values, if not eat them alive. Tormented by memories of the day the train took her from her hometown, Yeong-ja attempts to end it all by walking on the tracks in Seoul, only for the train to stop just before hitting her. Not her only thwarted attempt at suicide, it signals the sharpening of the downward spiral that will soon have her desperately seeking shelter in a brothel — and not long thereafter, looking increasingly pathetic before customers put off by her missing arm. At some point she resigns herself to her ever-lowlier status: “I just want to rot away as quickly as possible and die,” she insists to the slavishly devoted Chang-soo as he tends to her fingernails. “If you really care about me, you should leave me alone.”

Yeong-ja is the film’s primary victim, and that to an almost implausible extent, but she’s not its only victim: all the efforts Chang-soo makes to win over Yeong-ja, begun the moment he introduces himself to her as a fellow country bumpkin, turn out in vain. Those go beyond clipping her nails to include paying for her venereal-disease treatments and crafting a prosthetic arm in the bowels of the public bath house where he works. Both she and he belong, in the view of this story and the many others like it, to a generation used as human fuel by the breakneck industrialization of mid-20th-century South Korea. Drawn from the countryside up to Seoul — always “up,” by linguistic convention, no matter where the point of origin — by the prospect of gainful employment, many wound up in a lifetime of toil, and often not a long lifetime, in the capital’s dark satanic mills. Chang-soo may have nothing to show for his labor, but it took the story of a character like Yeong-ja, and the symbolic power of her descent into prostitution, to tug effectively at Korean hearstrings.

Yeong-ja’s Heydays tugged effectively enough to become a box-office hit, beating out The Sting, just the kind of profitable Hollywood movie coveted by Korean distributors. Initially marketed as a “youth film” daring to expose the moral turpitude of a generation running wild — a ploy not unknown in either the East or the West, then or now — it also founded the straightforwardly prostitute-focused, titillation-driven, less-than-straightforwardly labeled genre of “hostess films.” The Prostitution series would later take the hostess film to its sleazy limits (at least in my viewing experience), but for all its salaciousness, Yeong-ja’s Heydays remains safely within the realm of the Korean melodrama. Korean melodramas are also afflicted by their own excesses, to put it mildly, but like all the best examples of the tradition, this film hangs together on the strength of what Seoul-based American film critic Darcy Paquet calls “deeply felt sympathy for its lead characters.”

On the part of director Kim Ho-seon, this sympathy evidently ran deep enough to change Yeong-ja’s fate. In Cho Seon-jak’s original short story Yeong-ja dies in an accidental fire, an unsurprisingly sudden and terrible end to a life consisting of almost nothing but setbacks. The film adaptation lets her live and even find a kind of love, albeit not the kind she would have imagined in her housemaid days. Kim has ascribed this change to his desire for Yeong-ja to find redemption, although even in the low-pressure 1970s commercial considerations must also have played a part. (In the event, the film’s success made Kim one of the period’s major directors.) Our heroine even ends up with a family, confined though they all are to the landscape of dirt, barbed wire, and skeletal towers south of the Han River before it became today’s Gangnam. The film leaves her with a more fulfilling existence than it does Chang-soo, though he still gets to close it out by literally riding off into the sunset. This is, in its way, a happy ending — but still some way from a Hollywood ending.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Between Boring Heaven and Exciting Hell: Kim Soo-yong’s Night Journey

Wangsimni, My Hometown: a Gangster (and a Filmmaker’s) Pledge of Devotion to Korea

Bright Lies, Big City: Korean Authors and Seoul

“Hell Joseon” and Korean Literature

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.