The Korean relationship with big cities, particularly Seoul, mixes love with a strong undercurrent of hate. The love of Seoul is often clear: when I first got a job in Korea, which was in Daejeon, I called my best friend, who is Korean. Happy to hear that I got a job, he told the news to his wife, also Korean. “Where is the job?” he then asked. Woosong University in Daejeon, I replied, which he also dutifully relayed to his wife. In the background I could hear a small commotion, which was shortly interrupted by my best friend’s wife grabbing the phone from his hands and loudly yelling into it, “Why didn’t you get a job in Seoul? You won’t understand Korea unless you live in Seoul!”

Having come from Gwangju (another major city that, for historical reasons, I will talk about in my next piece), she regards Seoul with suspicion, if not contempt, but apparently still regards the capital the heart of Korea. Consider that, if you count the suburbs, Seoul contains nearly half of all South Korean citizens. Most high school students dream that they will someday attend one of the prestigious “SKY” universities: Seoul National University, Korea University, and Yonsei University, all in Seoul. Of the top ten universities in Korea, seven are in Seoul; of the top five, four are.

Most chaebol, the Korean version of the multinational, have headquarters in Seoul, and when the Korean government tried to move itself to Daejeon, the resulting foot-dragging and lamentation were so powerful that, in the end, only twelve of its offices made the move. Koreans even have a dismissive term for the land that is not in the city, sigol. The first literal meaning of this word is the countryside, but it more or less evokes the “sticks” or “backwoods.” The cities — and again, Seoul in particular — are also strongly associated with modernity, economic progress, and sophistication. Yet Korean modern literature has almost unanimously portrayed cities as uncaring dens of corruption, socially and/or economically destructive, and dangerous in every incarnation.

Yi Kwangsu, whom it is fair call one of the fathers of Korean modern literature, not only wrote extremely modern fiction for his time, but also wrote two extremely influential essays that defined the boundaries of modern literature. He was a proponent of modernization, education, and free love (as in, the ability to choose one’s own romantic partner). Yet in his fiction Seoul is nearly eviscerated, despite its apparent position as urban argument for all that he himself argued. Soil, his most entertaining novel, fully expresses his arguments and themes, strongly affirming the need for social and political change, but unexpectedly emphasizing the importance of the countryside in creating the modern world for Korea. Seoul, conversely, is portrayed as evil. In a close relationship to nature truth and beauty are found, and Seoul represents a turn toward a far worse, more Western world.

Its protagonist Heo Sung returns to his village and falls in love with a local girl whose down-to-earth virtues the story frequently contrasts with the corruption of the city girl whom he finally marries. He may admire the life of the villagers, but still has to return to return periodically to Seoul. The meaning of this is expressed in a concluding passage in the book: “When he got out at Seoul Station, he felt as if he had awakened from a dream. The swarms of fussy taxis, buses like frenzied women, toy-like rickshaws, the crowds of cold people who seemed to spread an iciness around them.” While Yi is a proponent of modernization, he astonishingly locates it in the rustic life of the countryside instead of the bballi-bbali hustle and bustle of Seoul, which only stands for the ruination of the Korean people.

Japanese colonialism and World War II turned Korea’s focus toward bigger and more immediate problems, and the overwhelmingly tragic reality of the Korean War and its bifurcated aftermath determined the course of literature in the 1950s and 60s. But with cessation of hostilities and the beginning of the regularization and modernization of the nation, the issue of the city returned — and the city was almost uniformly cast as the villain.

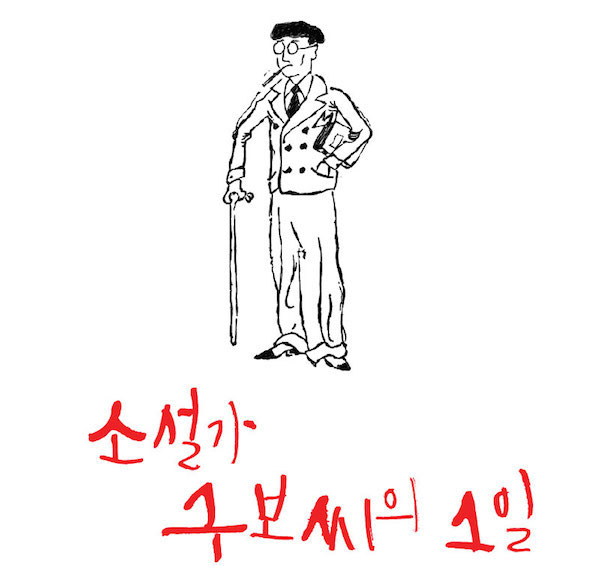

Not all literature, of course, portrayed Seoul or other cities as malign. Sometimes it could be neutral, or even charming, as in Park Taewon’s A Day in the Life of Kubo the Novelist, a slice of Kubo’s life in downtown Seoul. In a very modern stream of consciousness, occasionally interspersed with forays back into memory, Kubo takes us on a tour of the city, traveling to Gwanghwamun (the area around the main gate of Geyongbokgung pakace), bars, teahouses, a train station, and even past a row of prostitutes.

Little black and white drawings by the well-known author (and Park’s friend) Yi Sang capture aspects of the vignettes Kubo relates, which make up of a story that lasts part of the day and late into the night. Kubo is looking for “joy” and companionship, though he sometimes shies away from it when it comes, and it doesn’t necessarily calm his sometimes agitated mind. As Kubo wanders, mostly as an observer, with poet friends or bargirls, he contemplates his own history, which leads the setting of his final, bargirl-surrounded semi-epiphany in which declares his rededication to writing and the happiness of others.

A Day in the Life of Kubo the Novelist presents Seoul as a kind of charming backdrop, but in general, the bleak view of the big city dominates. In Sung-ok Kim’s 1965 story “Seoul: 1964, Winter,” three men meet just as atoms might collide, and just as when atoms do collide, they create a short heat before careening apart. These characters are Kim, a 25-year-old-clerk; Ahn, a 25-year-old student; and an unfortunate 30-year-old salesman who has just received payment for selling the corpse of his just-dead wife to a hospital.

Seoul is a randomizer; it can bring people physically together, but it cannot have them bond. The three men never get past idle chitchat, even though the oldest is obviously traumatized and funding their time together. Whereas in the village long-standing relationships would have established the bonds, in Seoul there are no relationships, and therefore no bonds. At the end of the evening, the salesman does all but beg the two younger men to share lodgings with him, but they both opt for private rooms, a substantial breach of protocol on several levels that eventually leads to tragedy. Even though the three men have been brought together by circumstance, they do not have the tools connect.

Cho Se-hui’s The Dwarf (1978) continues along these lines. The work centers on the government-mandated redevelopment of Seoul’s Hangbuk-dong neighborhood during the 1970s. “Those who dwell in heaven have no occasion to concern themselves with hell,” notes a character in the book’s very first paragraph. “But since the five of us lived in hell, we dreamed of heaven… Each and every day was an ordeal. Our life was like a war. Everyday we lost a battle.” The eponymous dwarf is physically handicapped, only 117 centimeters tall and 32 kilograms in weight, and his family — father, mother, siblings Yeong-su, Yeong-ho, and Yeong-hui — stand for the entire Korea working class of the 1970s: oppressed, marginalized, and if need be discarded by the new economic structures of production, consumption, and distribution that the Korean state is avidly building.

The family’s house, built in an unauthorized area, is due to be razed. The government offers a “recompense” for the loss insufficient for the dwarf’s family (or any of the other families displaced) to rent new housing. His family sundered, the dwarf becomes ill and dies in a factory smokestack, most likely in an act of suicide. His children are forced to go to work in soul- as well as body-crushing factories, and the daughter eventually prostitutes herself in order to get the deed to the families’ property back. Every character is in some way reduced, and one gets literally whittled down. (It is worth noting that the kind of forced redevelopment portrayed in The Dwarf continues, albeit on a reduced scale, to this day.)

The Dwarf is an example of yeonjak soseol, a kind of novel form of intentionally connected series of short stories gathered together, as is Yang Kwija’s stunning, well-translated A Distant and Beautiful Place. Its stories were originally published in Korean literary journals between 1985 and 1987 under a rather less interesting title that translates to People of Wonmi-dong.

Situated in Bucheon, south of Seoul, Wonmi-dong sits in the shadow of Wonmi Mountain, and there those who have failed in Seoul and consequently been ejected from it struggle, mostly without notable success, to build lives for themselves and their families. Beginning with a rather obvious symbolic chipping of a prized piece of furniture, one story focuses on the small “chipping” price that such forced departure from Seoul extracts from family members,. It ends ambiguously, and also ominously, with the family safely in place in their new home but watched by an unknown observer who brings an air of creepiness to the conclusion.

No survey of Korean city literature in English would be complete without a consideration of Kyung-sook Shin’s worldwide success Please Look After Mom (2008), translated by Chi-young Kim. Telling the story of a family coming to the realization of what their mother has sacrificed and what she meant to them, this book is so anti-Seoul that NPR titled its review of the book “A Guilt Trip To The Big City.”

“Mom liked it when all of her children and grandchildren gathered and bustled about the house,” one character notes during a sometimes overly nostalgic and romantic reverie of what life was before Seoul intervened and split the family geographically (that old trope of Korean literature). “A few days before everyone came down, she would make fresh kimchi, go to the market to buy beef, and stock up on extra toothpaste and toothbrushes. She pressed sesame oil and roasted and ground sesame and perilla seeds, so she could present her children with a jar of each as they left. As she waited for the family to arrive, your mom would be visibly animated, her words and her gestures revealing her pride when she talked to neighbors or acquaintances.”

Seoul is presented as a threat to this family unity: “At some point, the children’s trips to Chongup became less frequent, and Mom and Father started to come to Seoul more often. And then you began to celebrate each of their birthdays by going out for dinner. That was easier. Then Mom even suggested, ‘Let’s celebrate my birthday on your father’s.’” And “eventually, quietly, Mom’s actual birthday was bypassed.” The family’s sundering occurs at Seoul Station: “Mom and Father rushed toward the subway that had just arrived. Father got on, and when he looked behind him, Mom wasn’t there… Mom was pulled away from Father in the crowd, and the subway left as she tried to get her bearings.”

When the daughter returns to find her mother, she is similarly buffeted: “So many people go by, brushing your shoulders, as you make your way to the spot where Mom was last seen. You look down at your watch. Three o’clock. The same time Mom was left behind. People shove past you as you stand on the platform where Mom was wrenched from Father’s grasp. Not a single person apologizes to you. People would have pushed by like that as your mom stood there, not knowing what to do.” In breaking all traditional social relationships, Seoul has broken the family as well, both physically and psychologically.

Hwang Jung-Eun’s Kong’s Garden (2013), translated by Jeon Seung-hee, offers a glimpse of the experience of the postmodern city for the worker. In this future, the single unnamed female narrator never becomes anything more than that. Though education has historically meant everything in Korea, she comes to realize that this is not true. The recognition of this fact does not surprise her at all: when the narrator does realize that she has been nothing but a worker all her life, in a world of similarly little people working and dying, she displays no particular reaction beyond acceptance.

This equanimity is particularly dystopian in that this narrator also physically loses her mother during the events of the book. She metaphorically moves from a land of light, a bookstore gloriously lit with 200 light bulbs, to a dingy sub-basement that might be shrinking due to mold, but which also seems to have a mysterious tunnel leading to an even deeper, darker, room. That sub-basement, it is strongly suggested, is tied by another tunnel to an even deeper world, one from which a stench-laden breeze occasionally wafts out. Beneath the darkness of the city lies an even darker underworld.

A larger story draws the narrator in when she refuses to sell cigarettes to Jinju, a young woman in the company of two intimidating men. The young woman immediately goes missing, and it is only this tragedy that makes the narrator important at all, even as it minimizes her. As the police question her about her final interaction with the vanished girl, the narrator realizes that “the more important the questions were, the more often I told them I didn’t know.”

With life little more than a long, boring economic calculation, the narrator’s father plans to die when he feels himself an economic burden. She herself, when not idly searching the internet for evidence of the corpse of the missing Jinju, finds herself — with her romantic options, economic opportunities, and number of relatives dwindling away — agreeing with George Orwell’s suggestion that, in such circumstances, you should “just die poor and with anyone,” an ending to which the book seems to be drawing her.

Another dystopian view, this one of what would happen in Seoul if the continuing trends of family decay and income separation were taken to their full extremes, appears in Cheon Myeong-kwan’s Homecoming (2014), translated by Jeon Miseli. The book opens with everyone north of the Han River living as pathetic wards of the state, with a strong market in human organ trafficking a partial result. These so-called “blankets” wait in line to submissively accept abuse and vouchers, which they need for food and other necessities. On the other side of the river live the ten percent of the population who are employed, clasped to the bosoms of conglomerates.

One blanket, the father of a young boy whose mother left home years ago, is indirectly approached about his half-Korean child. Adopted children have become myeongpum, or valuable goods, with a child who appears in good health at a premium. The father attempts to buy drugs for his asthmatic son, but the prices have gone up because “some of the rich are up to tricks,” buying up steroids because of their usefulness against diseases of aging. Driven to despair, the father decides he must sell his son. As a goodbye, he dressed up, puts on a “badge” (proof of being an office worker, which he has luckily found) and goes out for one last grand dinner with his son so they can share at least one last happy memory.

When the bill comes and the father cannot pay, it is suddenly taken care of for by an old man at sitting the bar. The ending, either a surprise or a deus ex machina depending on the reader’s outlook, allows Cheon’s final point: this is the Korean tendency to insist on long work hours taken to its ultimately absurd extreme. “I haven’t been able to come home because I haven’t finished my work yet,” says one character who hasn’t been home in many years. In this vision of Seoul, even the “successful” are not winning.

Korean modern literature has, in some ways, always been reactive, focusing directly on real issues of its era, and so serious literati might naturally choose to take on Seoul, attacking the very concept of the big city. For while Seoul, on one hand, symbolizes the tremendous prosperity Korea has attained, also symbolizes the destruction of the previous social systems that had seen Korean society through times of extreme hardship.

Thus, in the works discussed here, the authors to some extent assume the successes of the city, proceeding from that point on to comment on the failures that have resulted. This means that Korean literature asks particularly strong questions about modernization, economic progress, commodification, and even the creation and status of the financially unstable “precariat” class — which means these books should hold great interest to readers everywhere as the same economic and social trends that have swept over Seoul in last century sweep over us, and will continue to sweep away for the foreseeable future.

Charles Montgomery is an ex-resident of Seoul where he lived for seven years teaching in the English, Literature, and Translation Department at Dongguk University. You can read more from Charles Montgomery on translated Korean literature here, on Twitter @ktlit, or on Facebook.