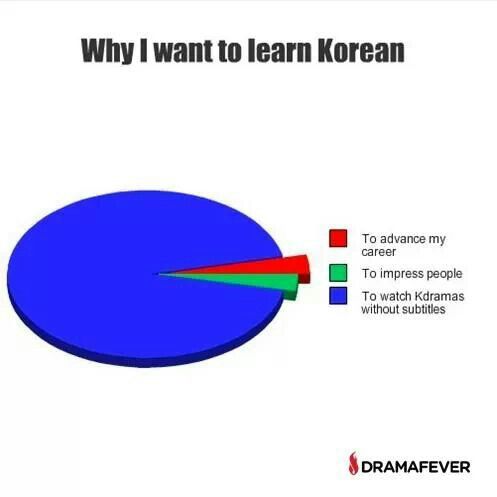

Worldwide interest in the Korean language has grown to enormous proportions — enormous, at any rate, compared to twenty years ago, when it might as well have had no proportions at all. Even I felt little desire to learn Korean back then, despite my having given precious megabytes on my Diamond Rio over to several Korean pop songs I’d downloaded through Napster. Now, culturally phenomenized in with the West as “K-pop,” this music and its performers constitute a hugely popular motivator to study the language — second only, perhaps, to the more verbally intensive if not necessarily more complex form of the Korean television drama. That both K-pop and K-drama have accrued international fan bases of such striking avidity owes something to the concurrent development of social media. And it is there, on what Konglish calls “SNS,” that Korean-learners express their collective frustration.

It always starts so easily. Unlike Chinese, written modern Korean uses not logographic characters but a phonetic alphabet, a fact I’d picked up even when I was listening uncomprehendingly to Baby V.O.X. back in high school. (Until not so long ago it mixed Chinese characters with the phonetic alphabet in the manner of Japanese, and now I’ve come around to wishing it still did, but that’s a subject for another day.) King Sejong the Great, the fifteenth-century ruler celebrated for having commissioned the creation of hangul, literally “Korean writing,” is recorded has having described it as learnable by a smart man in a day and a stupid man in a week. That claim seems to be true as far as it goes, made though it was without consideration of the far thornier difficulties for those who have yet to understand the language itself — a subject since addressed by memes.

With their easily legible found imagery and simple text, internet memes are practically tailor-made for circulation in a group like students of Korean, who apart from a debased “global English” may not have much language in common to begin with. But surely all of them can recognize the exhilaration of first learning hangul — which, smart or stupid, one can learn alone on the internet — and the immediate deflation of trying to read “real” Korean texts thereafter, let alone to make sense of overheard Korean speech. I can certainly recall the trepidatious thrill of early forays at using words and phrases of a newly acquired language on a native speaker. Indeed I should be able to, considering I felt it most recently when I went to Ethiopian restaurant here in Seoul earlier this month, on the day that country observes Christmas, and offered a memorized holiday greeting in Amharic.

I’ve made only the most preliminary strikes on the formidable-looking Amharic alphabet, or Ge’ez script. If I go further, my experience with Korean has primed me to treat the study of the written and spoken languages as two almost wholly distinct enterprises — or rather, as distinct but interdependent ones. As the late Kevin O’Rourke wrote in his memoir of his decades in Korea, a foreigner who doesn’t read widely in Korean can’t hope to master the language. But I can also tell you that the years of book-based self-study I undertook at first did little for my ability to actually speak Korean, or more importantly my ability to understand when spoken to in Korean. With little previous language-learning experience, I assumed I could get a handle on the mechanics of Korean grammar and syntax first, then fill in my vocabulary later, a plan few teachers would presumably endorse.

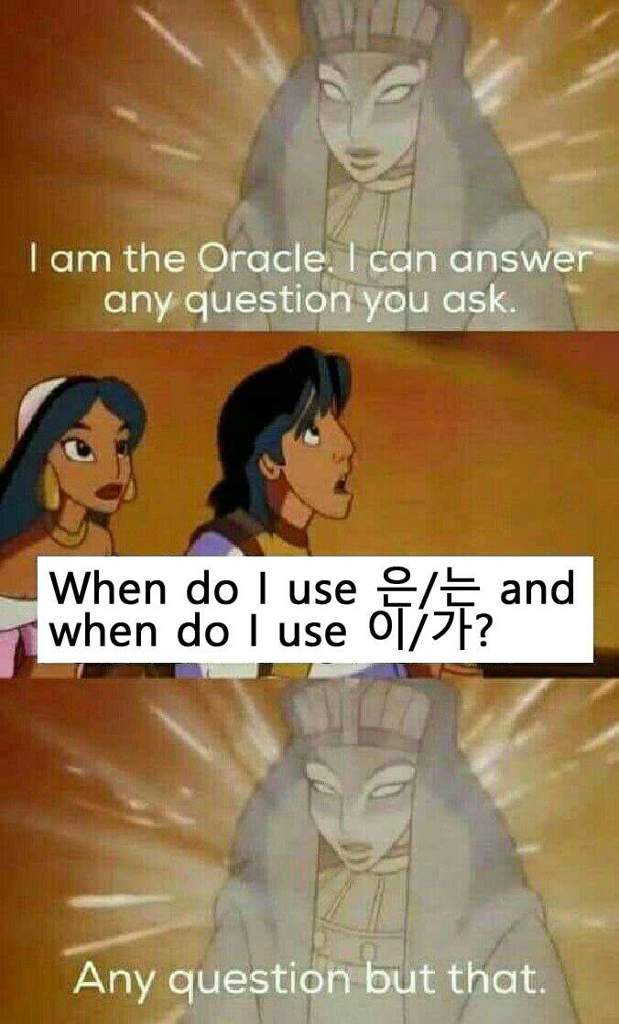

Yet this backward-sounding approach seems, in the long term, to have eased my own experience with certain of the most meme-rued elements of the Korean language. I speak, as Korean-learners will have guessed, of the markers eun/neun (은/는) and i/ga (이/가), which get attached to the end of nouns, though how and why remains shrouded in mystery to most Westerners for a time, and to some degree quite possibly forever. (In English, one is called the “subject marker” and the other the “topic marker,” names that, like many of Korean language pedagogy’s established practices, are of no help whatsoever.) Native Japanese-speakers have it easier, since they can adapt their language’s broadly similar markers wa and ga, but with yet to even start learning Japanese, I simply resigned myself to never fully understanding when to use eun/neun and when to use i/ga.

Nevertheless, more than a dozen years later, the last five of them spent in Korea, I now find myself — apart from isolated misplacements of emphasis — commanding the markers credibly enough. This doubtless owes less to any theoretical knowledge than to simply having heard and read them used correctly many times (though I remind myself daily that I could be getting more linguistic input than I do). Despite being at a Korean-learning disadvantage against the Japanese, familiar as they are with markers, and the Chinese, from whose language the bulk of the Korean vocabulary derives, most of us Westerners have enough experience with European languages not to get too intimidated by the comparatively straightforward and non-memorization-intensive verb conjugation in Korean. (And I’ve heard that if you’re looking for real trouble in that arena, you start studying not Spanish or French but Finnish or Magyar.)

More destabilizing to native speakers of such ostensibly egalitarian languages as English are Korean honorifics, the use of which, though not intellectually difficult, must be made into a reflex. Those who insist on the value of binge-watching Korean dramas as a language-learning practice are here on solid ground, turn as so many of those shows do on hierarchical family and corporate dynamics. (This makes the chattery, low-production-value “morning dramas” targeted toward stay-at-home mothers prime educational material, what with all their scenes set around the dinner table, in the boardroom, or at the hospital.) Though the levels of politeness used in everyday Korean life don’t reach the dizzying heights of, say, Japanese — where even competent speakers can be thrown by the elaborate verbal deference of a convenience-store clerk — this remains a society in which one can inadvertently deal a serious insult by failing to pronounce a single syllable.

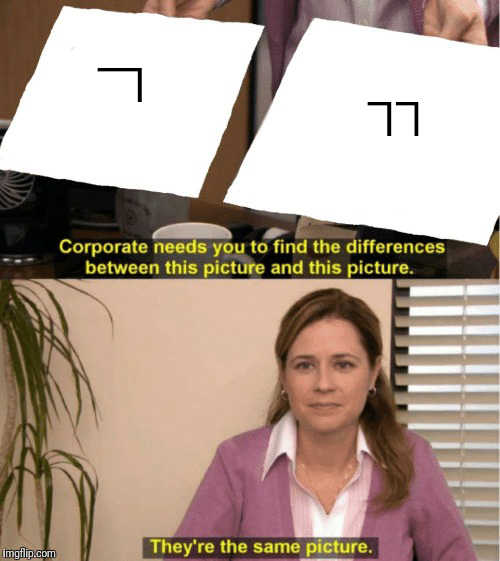

But you first have to distinguish one syllable from another, a task at which we all have our good days and bad. Occasionally I meet expatriates here of years’ or even decades’ standing who complain that they still can’t hear the difference between the plain “K” sound (ㄱ), the tense “K” sound (ㄲ) , and the aspirated “K” sound (ㅋ), the kind of fine but unignorable distinction that provides ideal meme fodder — and makes some hopeful Korean-learners quit no sooner than they’ve started. Others press on, developing feelings about the language complex enough to be expressible only by combinations of basic fonts, sitcom quotes, cartoon screen-captures, and animal photos. Easy-Korean.com has even published Korean Grammar with Cat Memes, Korean Words with Cat Memes, and Korean Phrases with Cat Memes, a series of textbooks books that, if nothing else, demonstrates a thorough understanding of its readership.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Learning Korean with Duolingo, the Mercilessly Addictive Language App

Talk Like a Busanian: How to Master the Ever-Trendier Dialect of Korea’s Brash Second City

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.