The summer after my freshman year of high school, I took a short computer programming class. Getting up to speed in C, the programming language of the day, looked like a daunting task, but the instructor reassured us: “Look, guys, I don’t expect you to learn C in two weeks any more than I’d expect you to learn Korean in two weeks.” I took his point, but the specific comparison baffled me: sure, great, but who on Earth would choose to learn Korean?

Now, living in Korea myself more than fifteen years later, I realize that I’d have done much better to take a class in Korean than that class in C, which even when it interested me I could never get much of a handle on. But at the time, Korean struck me as a hilariously obscure language to bring up: why not Japanese, at which I’d tried my hand a couple years before out of my love of Japanese video games without seriously imagining ever being able to comprehend it, or Chinese, which some Americans surely wonder, deep down inside, whether the Chinese themselves can understand?

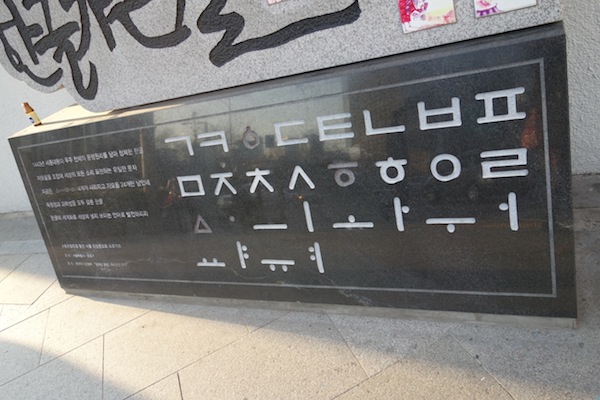

I didn’t give a another thought to that programming teacher’s remark until the year after college, as I hung around and plowed through all the Korean movies available at the university media library, eventually starting to suspect I could teach myself a thing or two about their language if I put my mind to it. Some time earlier, I’d learned the one thing about Korean that everyone who knows only one thing about Korean knows: its written language, known as hangul (한글), is just an alphabet with letters arranged into blocks, not a logographic language like Chinese (or the adapted-from-Chinese characters used in Japanese) which requires a massive amount of memorization even to approach functionality.

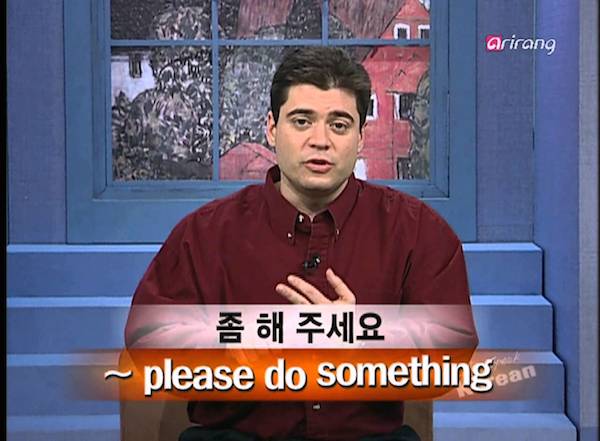

And so, during idle moments at work, I began studying Korean, a language expressed in what one often hears described as “the most scientific writing system in the world,” as if the linguists of all nations had with one voice declared it so. Those words, as far back as I can trace them, came from Edwin O. Reischauer, U.S. Ambassador to Japan and co-creator of the old McCune-Reischauer Korean romanization system. If any language has no need for romanization systems, it’s Korean: they tend to get mixed together in practice, none reflect the actual pronunciation very well, and you can get each and every one of the real letters down with only a modest layout of time and effort.

“A wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over,” declared King Sejong the Great, who commissioned the creation of hangul in the 15th century. “A stupid man can learn them in the space of ten days.” A slight exaggeration, perhaps, but the height of Korea’s literacy rates more or less bear it out. For many Korean-learners, the speed and intuitiveness with which they learn hangul gives them a sense that the rest of the language will come easy — a false sense, as it turns out. Even after the first four or five years I spent studying, and even when I knew all the relevant vocabulary and grammar, I still couldn’t understand anything actual Koreans said to me.

Now, with at least eight years of studying under my belt, many Korean classes taken, hundreds of hours logged with Korean podcasts, Korean videos, and Korean speaking partners, and a fair few Korean books read (some, even, without pictures!), I can get a bit of conversational traction. I still have a long way to go, but when I look back at all those years filled with waves of frustration during which any reasonable person would have put the language away and never picked it up again, I do finally feel confident that my obsessiveness will see me through.

Living in Korea speeds the learning process, no doubt, but it’s far from a guaranteed road to proficiency. “One of the things that distinguishes the expatriate community here from the expatriate community in Japan and China, even now, is that the percentage of foreigners who learn the Korean language is much lower,” said the Busan-based American North Korea analyst Brian Reynolds Myers when I interviewed him last year. “If you go to Beijing, I think I’m correct in saying that the average long-term expatriate speaks pretty good Chinese — certainly good by my standards. In Japan as well, I’ve heard a lot of expatriates speaking Japanese to a higher degree of fluency even than the foreigners here in South Korea who are so famous for their Korean skills that they’re on TV every week.”

One part of the problem, according to Myers, is that “the Koreans do not demand Korean language skills. I’ve often had Koreans apologize to me for not being able to speak English, and I always have to say, I’m the one in Korea, I’m the one who should be apologizing.” Another is that “people do not come here with the intention of living here for a long time. Korea is not a country that foreigners fall in love with to the extent that they fall in love with China or Japan. You get foreigners who come here thinking they’re going to stay for one year, and that becomes two, three, and after a while they’ve been here six or seven years, and they’ve just got this survival Korean.”

All this creates an environment not especially conducive to mastering the language. Still, I seize every practice opportunity that comes my way, and that often, when speaking with a stranger, results in the same question: “Why are you interested in Korea?” The acknowledged catalysts for an interest in Korea include pop music, television dramas, movies, food, money (especially the making thereof as an English teacher), and professional computer gaming, but the most truthful answer I can give — the one that most fully accounts for why I’ve come to live here — is the language itself, which few Koreans ever seem to accept.

Some of that disbelief may owe to the difficulty of the Korean language, or rather the difficulty Koreans imagine it visits upon the non-native speaker. But even though Koreans know their language is hard, they don’t usually know why. For some reason, almost all of them cite the example of how many different words it has to express colors, especially the color yellow. (Taxi drivers who want to regale you with the magnificence of the Korean language will say the same.) But this cultural meme, no matter how widespread, has little to do with the very real walls a Korean-learner keeps running into, no matter how long they’ve studied.

“The problem for me is the lack of a really developed grammar that I can rely on,” said Myers. “The first foreign language I learned was German, and one of the things I love about German is that it gives you a bunch of rules you need a year to memorize, and you follow the instructions pretty much without exception. But in Korea, you’re constantly coming up against things that are a question of feeling. My Korean teacher and I, we just come close to strangling each other every week because she cannot explain to me why something sounds funny — it just does. I get the impression you really need to have heard every single sentence, at some stage, in order to generate a similar sentence in the future.”

Another of the reasons so few Koreans buy my story about the language attracting me here may come from one of its qualities that most fascinates me, and one that stands out to any native speaker of English, which can afford to make no assumptions about speaker or listener. Korean, to a degree unique among any of the languages of my acquaintance, is inherently geared toward not just one nation but one ethnicity, embedding the assumption that both speaker and listener are Korean into its very vocabulary. The words hangugeo (한국어) and hangugmal (한국말) refer to the language itself, but more commonly, you hear uri mal (우리 말) — “our language.”

If I referred to English as “our language,” nobody, including me, would know whom I meant as the we. (I’ve tried doing so to Koreans as a joke, but they never get it.) Anyone who hears and understands the word uri, however, knows exactly the we in question. Sometimes it gets romanized as woori — Korean romanization, again, not being known for its iron consistency — which you might recognize from the names of such Los Angeles Korean businesses as Woori Market and Woori Bank. Listen for the word in Korea and you hear it all the time, especially in the media, where, as often as you hear the actual name of Korea, you hear uri nara (우리 나라) — “our country.”

This sort of thing goes as deep as you want to look for it, but other fairly obvious examples (not that I stopped to consider them until a friend with more experience in the language pointed them out) include words like hanbok (한복) which refers to traditional dress of 1392 to 1897’s Joseon dynasty but literally means just “Korean clothes”; the aforementioned hangul, which literally means just “Korean writing”; and hanu (한우), which refers to the species of cattle bred here but literally means just “Korean cattle.” That the language adheres so closely to the land hardly comes as a surprise, since no country outside the Korean peninsula speaks it, but that aspect sometimes makes it seem a category apart from such less insular languages as English, Spanish, or French (or even, in some respects, the pretty damned insular Japanese).

Does the resultant feeling of non-inclusiveness put off foreigners who would have otherwise thrown themselves into the study of Korean? (As one longtime Korea-resident Westerner once put it to me, his speaking just a few words of Korean often draws a “How do you know our secret code?”-type reaction from the locals.) Or does more of it come down to the fact that, in time, a foreigner can too easily convince himself — working in English among only the highly educated, socializing in expat bars, letting his Korean wife take care of business — that he doesn’t need the Korean language in Korea?

Before moving here, I most feared the prospect of turning into exactly that kind of foreigner. Maybe that very fear motivated me to study Korean for eight years before arriving. I’ve hardly learned all the Korean I need to know yet, and certainly not all the Korean I want to know, but the more I learn — and I make a point of learning on a daily basis — the fuller a life I lead. The language has only become more fascinating with time and knowledge, and so I wonder whether Korea, a country always looking for pieces of itself to market to the outside world, might one day start putting as much energy into promoting uri mal as it puts into marketing bibimbap, Hyundai and Kia cars, or Girls’ Generation. And given the country’s zeal for English-language slogans, how about this? The Korean Language: Don’t Stay Here Without It.

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook. Catch up on the Korea Blog’s archives here.