Lulled into a false sense of security by the simplicity of its alphabet, those students of the Korean language who don’t give up in frustration will sooner or later find themselves facing a variety of unexpected challenges of communication and comprehension. Nearly a decade after learning that deceptively easy writing system, I still often get unintentional laughs from Korean interlocutors myself, especially when I fail to recognize one of the many words they borrow from my own mother tongue. “What, you don’t speak English?” they jokingly ask, but in fact I don’t speak Konglish, that curious hybrid of Korean and English now so commonly heard south of the 38th parallel.

Rather than an oscillation back and forth between the local language and English, as in the Philippines’ “Taglish,” Konglish fills Korean grammatical structures with English loanwords. Often those latter replace existing Korean words: you now take pictures with a kamera instead of sajingi, enroll in a class of a certain rebel instead of sujun, and draw up a riseuteu instead of a mogneok. Owing to the difficulty of consistently pronouncing these Konglish words in the “correct” Koreanized manner when my adult language-learning brain stubbornly wants to pronounce them in American English as it always has, I tend simply to use the old words and accept the strange looks they draw as the cost of doing business.

Not that Koreans’ Konglish doesn’t draw strange looks from me. That goes especially for its outer reaches, a harbor for those faddish terms beyond the simple realm of cameras, levels, and lists which, long dead in America, turn out to have drifted across the Pacific to be reborn. Past decades saw attempts to purify the Korean language in the face of mounting “English fever,” but by the 1990s none could hold fast against the mighty tide of buzzwords from American media, business, and technology, with the result that millions of Koreans now walk around sounding like characters out of Dilbert. Here are but five of the many words that, seldom if ever heard in America in English anymore, see use each and every day as Konglish in Korea.

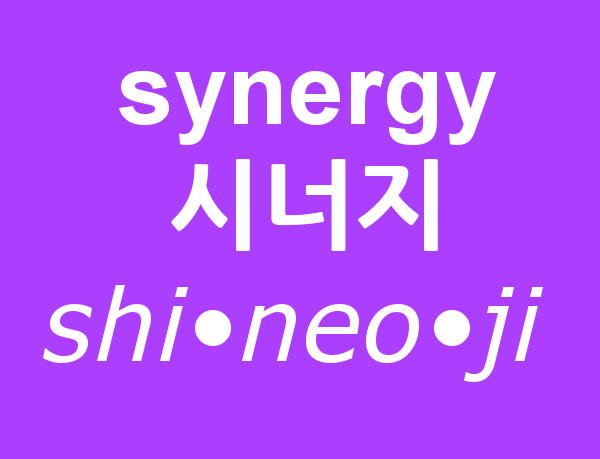

Shineoji (시너지). Once I bemoaned to a Korean friend my persistently unequal proficiency in different aspects of the Korean language: I could write a magazine article, yet on some days could barely sustain a conversation. “Don’t worry,” she replied. “Eventually there will be a synergy between them.” Only when I heard her use that term in English did I realize how often I’d been hearing everyone else use it in Konglish. If I had to guess as to why the concept of synergy, thrown around so recklessly to elide blanks in the business plans of the first dot-com boom, still enjoys such a widespread popularity in Korea, I’d put it down to the dominance of business conglomerates. Known as chaebol, each one of them — Samsung, Hyundai, Lotte, and so on — owns businesses across a variety of sectors from steel to insurance to entertainment to department stores, many with little or nothing to do with each other. Yet the chaebol system lifted Korea into the developed world, so hey, that must’ve been some serious synergy at work!

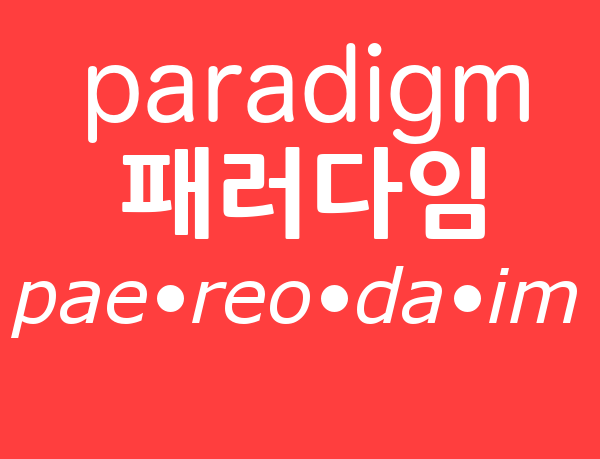

Paereodaim (패러다임). Seldom does a day go by here without my hearing some declaration of intent to change a paradigm: in living, in working, in frying snack foods. Though the word proved too vague for widespread adoption even in a country as mealy-mouthed as America, its fits right in with the host of capacious abstract nouns the Korean language can’t seem to do without. Here people don’t discuss what a book or a movie is about; they discuss what its naeyong (loosely translatable as “content”) is about. Instead of saying someone or something looks a certain way, they discuss its moseup (even more loosely translatable as “form” or “figure”). The time, energy, resources, absence of other obligations, and emotional readiness required to do what you want to do all get mashed up into the concept of yeoyu. In that respect, it almost surprises me that paradigm didn’t originate in Korean in the first place.

Netijeun (네티즌). “Welcome to the 21st Century,” wrote theorist Michael Hauben in the early 1990s. “You are a Netizen (a Net Citizen), and you exist as a citizen of the world thanks to the global connectivity that the Net makes possible. You consider everyone as your compatriot.” In the connected future he envisioned, “geographical separation is replaced by existence in the same virtual space.” Yet even as the internet pervades nearly every corner of the inhabited world, geographical separation has proven a more deeply stubborn condition than Hauben or the Wired-reading techno-optimists of his day had reckoned. When the Korean media covers the opinions of the country’s netijeun, as it so often does, they speak mostly, and forcefully, about domestic issues. Part of this must have to do with Korea’s getting internet infrastructure, and then broadband, well ahead other countries, and part with the “real name system” that for several years tore down the barrier between online and offline life. Whatever the cause, Koreans began taking their concerns as citizens to the internet long before 21st-century social media (a phenomenon Hauben could hardly have foreseen) turned the rest of the global — or geullobeol — population into cable-news pundits.

Seupek (스펙). Americans who’ve never worked in technology or manufacturing may never have heard the term spec, but even in the lives of Koreans with no interest in those sectors its Konglish version looms large. Whereas products everywhere have to meet a certain set of technical specifications, or “spec” for short, in Korea human beings must also attain a certain level of seupek. The idea goes back at least to the 1960s, when this country, still ruined and impoverished by war, had no choice but to create an export-driven economy in order to build itself back up — and if you want to succeed with exported products, you’d better make sure they’re up to spec. But what worked well for washing machines and cargo ships works less well for college applicants, job seekers, and marriage partners, all of whom clamber over each other, increasingly in vain, for the very same advanced degrees, experiences abroad, English skills, and cosmetic surgery procedures meant to qualify them for life.

Nohau (노하우). Konglish has drawn some of its most frequently used words not just from passé English, but from downright quaint English. “Remember know-how?” asked Jan Morris in “The Know-How City,” her 1976 essay on Los Angeles. “It was one of the vogue words of the forties and fifties, now rather out of fashion. It reflected a whole climate and tone of American optimism. It stood for skill and experience indeed, but it also expressed the certainty that America’s particular genius, the genius for applied logic, for systems, was inexorably the herald of progress.” Korea has, to a great extent, kept the faith, and every enterprise here from cram schools to information-technology consultants to pizza joints trumpets the value of their own nohau. It’s easy to laugh at that — and back in America I never once heard the original term used unironically — but no other expression adequately evokes the same combination of skill, knowledge, technique, and experience. I now wonder how I ever lived without it.

Korean linguistic conservatives occasionally rail, not without reason, against the corruption of uri mal (literally “our language,” heard much more often than hangugeo, or “Korean”) by these and other ungainly English loanwords, but they’ll all fade away sooner or later, whether shunted aside by the next national return-to-our-roots spasm or replaced by the coming avalanche of new Chinese terms. In a way, though, that will be a shame, since every loanword tells the story of its own fascinating journey. Much 20th-century history lies buried, for example, in alba, the word for a part-time job that comes from the Japanese arubaito, which itself comes from the German arbeit. Agiteu, my personal favorite, means a comfortable getaway or hiding place but comes from agitpunkt, the Russian word for a propaganda center originally brought in by leftist student groups sponsored by North Korea — a land that would never dream of using an English word when they’ve already got a perfectly good Korean one, but that, as we say, is another seutori.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Korea’s English Fever, or English Cancer?

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.