When a 92-year-old woman by the name of Lee died at last year, all of South Korea took notice. Her passing reduced to eighteen the official count of surviving Korean “comfort women,” who as girls were kept in sexual servitude to the Japanese military during the Second World War. Six months later, University of Washington press published an English translation of a Korean novel that imagines the future, inevitable and surely not far off, when that number falls to one. But an official count is just that, as Kim Soom reminds us with the character of One Left‘s 93-year-old protagonist P’unggil, a former comfort woman who never registered herself as such with the government. The death of the second-to-last member of the acknowledged group plunges her into an extended recollection of her own experience, which constitutes this “first Korean novel devoted exclusively to the subject of the comfort women.”

Georgetown University Korean studies professor emerita Bonnie Oh emphasizes this distinction in her foreword to the English version of One Left (한 명), translated by Bruce and Ju-chan Fulton. (Previously on the Korea Blog, we’ve featured their translations of Kim Sagwa’s novel Mina and Yoon Tae-ho’s comic Moss, as well as What Is Korean Literature?, a study co-written by Bruce Fulton.) The novel also, she adds, “rebuts denials of the validity of the comfort women’s claims by synthesizing an intense personal story with painstaking historical research.” The idea of a novel as a vehicle for rebuttal, or for argument of any kind, will give some Western readers pause, though it’s hardly unheard of in Korea. Cho Nam-joo’s Kim Ji-young, Born 1982, which appeared in English last year, was nothing if not a novel-shaped set of claims about the lousy lot of Korean women in the 21st century.

Like Cho’s book, One Left also comes with citations, and in parts fairly bristles with them. These superscript numerals accompany passages that recount events or provide character detail, functions that will strike most Western readers as having no obvious relationship to statistics, articles, studies, or any other kind of sources usually collected in endnotes:

People have no clue where she’s been or to what she’s been subjected.2

They can only assume that her marriageable years were spent drifting from one housemaid job to another. She never imposed on her family but could never bring herself to spill the truth even to her younger sisters, who considered her a burden and an eyesore: that she hated men; the mere sight of them made her shudder,3 made her wish she had a gun with a silencer so she could exterminate them.4

Any talk of marrying her off sent her ballistic.5

What Kim copiously cites is in fact the testimony given by former comfort women themselves, with whose elements she crafts the experience of P’unggil and the other girls she remembers from her seven years at the “comfort station.” During that time “thirty thousand Japanese soldiers came and went from her body,” which sounds agonizing enough even without the host of other gruesome details Kim incorporates into the narrative. Yet despite being as viscerally discomfiting as anything I’ve read, they’re somewhat blunted by the marks flagging the research that underlies them. This is an irony, given their ostensible emphasis of the fact that these atrocities belong not to imagined fiction but genuine history. Lines like “She was barely 13 and her underdeveloped genitalia wouldn’t admit him30″ or “The rods came out with charred flesh stuck to them22″ read as grotesque in more ways than Kim must have intended.

All these qualities made One Left a hard sell to English-language publishing houses, as the Fultons recount in their afterword: “‘How are we to market this book?’ they asked. As a historical study or as a work of literature?” Academic publishers suggested they take it to a non-academic publisher; non-academic publishers suggested they take it to an academic publisher. Another factor would have been the potential radioactivity of comfort women as a subject, which only a brave observer of Korea indeed approaches without first determining the currently acceptable frame. Within Korea, scholars of that grim chapter of history have even found themselves taken to court by comfort women or their advocates for publishing, as Harvard Law School professor Jeannie Suk Gersen recently put it in The New Yorker, “anything short of a purist story of the Japanese military kidnapping Korean virgins for sex slavery at gunpoint.”

The occasion for Gersen’s piece was the International Review of Law and Economics‘ publication of “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War,” an article by her colleague J. Mark Ramseyer. In it he claims, according to Gersen’s summary, that “Korean comfort women ‘chose prostitution’ and entered ‘multi-year indenture’ agreements with entrepreneurs to work at war-front ‘brothels” in China and Southeast Asia.” This is a far cry from the experiences included in One Left, with its daughters of the impoverished countryside falsely promised work in places like factories and hospitals — or simply snatched up while drawing water from a well or gathering snails on a riverbank. Not long thereafter, they find themselves hauled up to Manchuria (then “the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo,” as it’s almost invariably described today), confined to a small room with a filthy mattress, and ordered to “take soldiers” for the indefinite future.

At issue, clearly, is to what degree comfort women took up their role voluntarily, and the relevant arguments tend instinctively to be perceived as occupying one extreme or the other. Few could come away from One Left believing that any girl would actively sign up to work at a comfort station, no matter how dire her life back in the village. Indeed, Ramseyer’s article seems mostly to have been persuasive among Japanese ultra-nationalists — a group that needed no persuasion in the first place — many of whom surely encountered its argument at a degree or two of remove. Gersen identifies in its publication evidence of a deeper weakness in legal academia, where specialists “are often expected to review writing in areas on which they are far from expert, involving historical contexts they have not studied and languages they do not know.”

Yet if every piece of shoddy scholarship were to make the news, humanity could pay attention to nothing else. Whatever its flaws, Ramseyer’s paper touches a third rail, that of not just comfort women but Korean comfort women, the ones memorialized by the often-controversial “Statues of Peace” installed across from the Japanese embassy in Seoul and around the world (even, to high-profile local Japanese opposition, in Glendale, CA). Estimates of the total number of comfort women range from 20,000 to 400,000, and in One Left Kim makes multiple references to a figure of 200,000 taken from the then-Japanese colony of Korea alone. But history has recorded them as having come also from China, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, and even Japan itself — that last detail being one that puts the country in an even worse light, to my mind, but not one generally admitted into the conversation here.

There could be few entities less sympathetic than the Japanese military in World War II, whose brutality and incompetence (characteristics few Westerners associate with modern Japan) turned into a crazed, nihilistic desperation as defeat began to look inevitable. Most of its soldiers come off in One Left as less human than animal: what else would display such violent eagerness to be one of dozens each day to bed the same barely pubescent female, quite possibly diseased and — as Kim depicts them — almost certainly crawling with fleas? Yet the novel also offers occasional glimpses of relationships that suggest the soldiers and the comfort women have more in common than it may seem. One of P’unggil’s young compatriots passes on word from a favorite “regular”: “He said they were separated from their parents and siblings just like us and ended up here in Manchuria just to offer up their lives.”

Others have been legally roughed up for acknowledging this kind of thing. “In 2015, a Korean academic named Park Yu-ha was sued civilly by comfort women for defamation, and criminally indicted by Korean prosecutors, for the publication of a book that explored the role of Koreans in recruiting the women and the loving relationships that some comfort women developed with Japanese soldiers,” Gersen writes. And in their afterword to One Left, the Fultons stress that “those who fear that the novel is a case of Japan bashing should note that among the various characters responsible for coercing the Korean girls into sexual servitude, either through blandishments involving a ‘good job’ in a factory or through threats, are Koreans themselves” — a fact demonstrated, they add with a punctiliousness echoing that of Kim’s main text, “through research conducted by Chunghee Sarah Soh for her pioneering study The Comfort Women.”

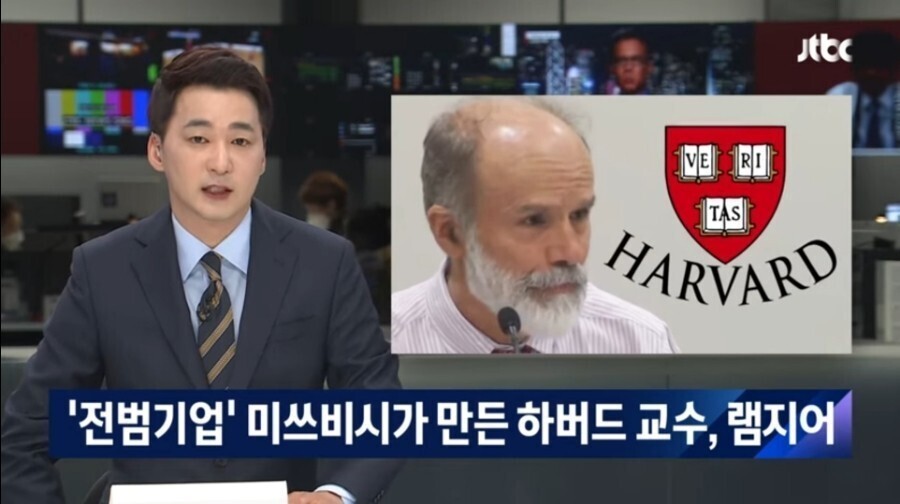

One Left was originally published in Korean in 2016. That the book took as long as it did to find a publisher in English perhaps turned out to its advantage, still new as it was when the “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War” controversy erupted. The two works even have an odd complementarity, the unusual form of rigor evident in Kim’s novel setting it as far apart from the literary mainstream as the apparent patchiness of Ramseyer’s article sets it from the scholarly mainstream. Gersen assesses her colleague’s argument and finds it wanting with a level-headedness as characteristic of her own writing as it has been absent from the reactions so far aired in the Korean media. A typical news broadcast here labeled Ramseyer, Harvard Law’s Mitsubishi Professor of Japanese Legal Studies, as “the Harvard professor made by the ‘war-criminal corporation’ Mitsubishi.”

Ramseyer’s paper has drawn so much attention not just because it questions the word of Korean comfort women, but also because of his association with Harvard, which as scholar of Japanese history Tessa Morris-Suzuki says to Gersen “gives it a degree of prominence and respectability.” It would be difficult to overstate the value of the Habeodeu brand here in Korea, where the United States’ best-known university has an even greater cachet than it does in the United States; to witness the Ramseyer-versus-comfort-women story enter the South Korean zeitgeist is to witness two powerful currents of public instinct crash directly into one another. In the West, readers not directly invested in the issue (and already told of Japan’s wartime behavior by bestsellers like Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking, criticized though her scholarship has also been) seem to take the stories of comfort women at face value.

Having heard no credible reason to doubt the comfort women myself, I read One Left as more a historical account than not, accepting its depiction of conditions in the comfort station as not employment, indentured or otherwise, but imprisonment. (“You can check in any time you want,” as one girl there jarringly puts it, “but you can never leave.”) Though the book certainly fulfills Bonnie Oh’s claim of its being the first Korean novel devoted exclusively to the subject of the comfort women, the emphasis belongs on the word “exclusively.” Apart from some reflections on P’unggil’s mostly abandoned neighborhood and the urban redevelopment that may or may not come for it (a motif shared, coincidentally, with Kim Hyun-seok’s 2017 comfort-woman comedy I Can Speak), this narrative is about one thing, and all the way through it exudes a reluctance to depart for long from the horrors of wartime sex slavery.

What would have resulted if, dealing with these same themes, Kim had chosen to labor under a lighter burden of conveying the specific experiences remembered by real comfort women? An experienced and acclaimed novelist hardly unacquainted with the power of imagination, she first made her name in a realm well apart from realism. Only in recent years has she taken the turn toward direct confrontation with historical and political matters that has produced both One Left and L’s Sneakers (L의 운동화), a novel about the life of Lee Han-yeol, a Yonsei University student martyred in the pro-democracy demonstrations of 1987. The 1980s and the 1940s both constitute relatively recent chapters in the history of Korea, and as such, subjects that require careful choice of words. An unconventional approach may still be necessary for writing about events in living memory, even those fast slipping out of it.

Related Korea Blog posts:

From Language Lessons to Sex Slavery: Korea’s New Comfort-Woman Comedy I Can Speak

A Liberation Day Protest Raises the Question: How Anti-Japanese Is Korea, Really?

The Book of Jiyoung: An Explosively Controversial Korean Feminist Novel Comes Out in English

The Making of a Korean Monster: Kim Sagwa’s Bloody High-School Novel Mina

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.