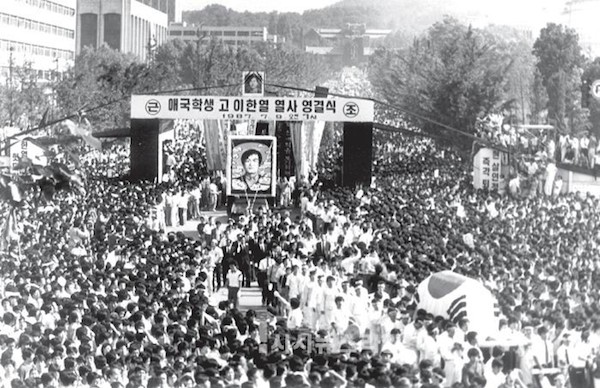

At least once a week I walk by something called the Lee Han-yeol Memorial. Though located in a nondescript building down a side street full of them, it catches my eye every time, and at first got me me wondering, no doubt by design, who Lee Han-yeol was. Not that his dates, 1966-1987, didn’t already give a big historical hint. If an American man born in 1950 died in 1968, it brings to mind the Vietnam War; if he died 20 years later, AIDS. By the same token, if one hears of a Korean man born in the early to mid-1960s, the time of South Korea’s own postwar “baby boom,” who died in the 1980s, one might well wonder if he counts among the country’s martyrs for democracy. Lee turns out to rank near the top of that list, and though I didn’t know him by name, I did already know the story of his death, one cinematically told in the new 1987: When the Day Comes.

I never noticed any change in the appearance of the Lee Han-yeol Memorial until a few weeks ago, when on one of its outer walls appeared 1987‘s poster. Advertised for months in the run-up to its release this past week, the high-profile, star-studded picture ends in June of that year, just after by the encounter with a tear-gas grenade that killed Lee. It begins the January before, just after the fatal torturing of Park Jong-chul, a Seoul National University student activist detained by the authorities for questioning as to the whereabouts of his fellow agitators. The story relflects widely accepted narrative of South Korean political history that frames that year, and especially its series of protests known as the “June Struggle,” as the most critical period in the country’s transition from military dictatorship to democracy.

It also joins a recent spate of popular Korean films based on the country’s troubled decades between the Korean War and the end of the 20th century: Yoon Je-kyoon’s Ode to My Father (국제시장) told nearly the whole story of the country through the story of one fictional man. Yang Woo-suk’s The Attorney (변호인) dramatized the depredations of anti-communist paranoia through an episode in the thinly veiled life of Roh Moo-hyun, who defended accused North Korea sympathizers in court in the 1980s before his time as president in the 2000s. Jang Hoon’s A Taxi Driver (택시운전사) looked at the Gwangju massacre of May 1980 through the eyes of titular cabbie who took a German journalist there to report on it. Most recently, Kim Hyun-seok’s I Can Speak made an only ostensibly lighthearted comedy out of the situation of the young Korean women made to serve as “comfort women” for the Japanese army during the Second World War.

Well before all those came Im Sang-soo’s The President’s Last Bang (그때 그사람들), a black comedy about the assassination of eighteen-year developmentalist dictator Park Chung-hee by the director of his own intelligence agency. When it came out in 2005, that movie found itself served with a lawsuit from Park’s son for mixing documentary footage of protests in with its fictionalized story. These more recent films, by contrast, make their integration with the historical record a point of pride: A Taxi Driver incorporates actual footage of the Gwangju massacre, and 1987 uses it in a scene when Lee and a few other Yonsei University students, disguised as members of a drawing club, secretly screen a tape of it on campus behind closed blinds.

The movie also, alongside its closing credits, shows its audience documentary footage of the June Struggle protests as well as the real Lee’s clothes and shoes (viewable at the Lee Han-yeol Memorial), as if to underscore the faithfulness of the foregoing recreation. And indeed, his slow-motion death scene does culminate in an image that closely resembles the iconic newspaper photo of the critically injured Lee being carried off by a fellow demonstrator. But those scenes also play with a certain uncanniness, filmed as they were at the actual gates of Yonsei University, which I regard from the window of a student-filled coffee shop across the street (a resurrection of one that existed in the 1980s) as I write these very words. Though I live right nearby, I somehow never noticed the shoot that, presumably not long ago, re-staged this bloody conflict between student and soldier.

Then again, many members of Korea’s middle class must never have noticed the protests either, or must have tried not to notice them, back when they were actually happening (and putting out actual tear gas fumes). Though the student protestors of the 1960s-born “386 Generation” often get credited with ushering in South Korea’s democratic revolution, historians may argue forever about how much change they personally effected. P.J. O’Rourke, observing the students in frenzied action first-hand, memorably recorded the strangely circular reasoning behind their demands: “But what is democracy?” “Good.” “Yes, of course, but why exactly?” “Is more democratic that way!” And in any case, political change of that magnitude needs to bring on board the bourgeoisie, a group known for valuing stability above all else.

Change comes, in other words, when the middle class wants it, and the nature of the deaths of college students like Lee Han-yeol and Park Jong-chul, once they became widely known, did make Korea’s middle class sit up and take notice. “In Korea, when popular feeling pushes past a certain limit break, it warps into a beast that is powerful enough to rip through decision-making and the established law,” wrote The New Koreans author Michael Breen in Foreign Policy last year. This beast of “public sentiment” is the country’s “collective soul, and it is considered supreme. Koreans even have a saying about it: ‘The law of public sentiment is above the law.'” As longtime pro-democracy activist and President of South Korea from 1998 to 2003 Kim Dae-jung put it, “The people are God.”

Breen’s piece appeared just after the downfall of Park Geun-hye, daughter of Park Chung-hee and President of South Korea herself from 2013 until the people saw “a TV report that said their president was being manipulated and essentially being told what to do by a lady who was completely unknown to the public. A few weeks later, the president has been impeached.” It happened so much more swiftly than a Westerner might consider the standard speed of the democratic process due to sheer force of public sentiment: “The reason the beast has been awoken to fury now is because Park strayed onto the path of heresy. She put her friend Choi Soon-sil up on the altar and bowed down before her, not the people – and in doing so, she broke the first commandment: ‘Thou shalt have no other gods before me.'”

1987 essentially tells, in the shakily-shot tension-filled style of a modern TV crime drama, a tale of the awakening of Korean public sentiment, leading up to it with the acts of a host of everyday figures whose probing of Park Jong-chul’s death made that awakening possible: prosecutor, doctor, prison guard, reporter, most of them based on real people, many played by famous 386-Generation actors. But the closest character this ensemble film has to a protagonist is a college girl named Yeon-hee played by Kim Tae-ri, an actor yet to be born in 1987. Though based on no single person in particular, Yeon-hee plays several necessary functions, first tying together several of the film’s many threads by passing along secret messages taken down by her uncle the prison guard and growing close to Lee in the midst of a brawl with the police.

Yeon-hee also helps to establish the period by listening to the music of Yoo Jae-ha (another young casualty of 1987, albeit not a political one) and gives 1987‘s younger viewers, much in evidence on the opening-day screening I caught at the theater across the street from my home (and thus not far from either Yonsei University or the Lee Han-yeol Memorial), a character to connect with. She would hardly look out of place on the likes of Reply 1988 (응답하라 1988), a recent, hugely popular television series set in that year that has, if not set off a full-blown Korean retromania, then at least made it fashionable to look back at the relatively recent past. The distant past, by contrast — especially the 500 or so years before Japanese colonization — has long provided material for movies and television shows, so often that their renditions of events tend to mix inextricably in the facts of history as popularly understood.

A film like 1987 evidences an understanding of this power of mainstream historical fiction to shape the perception of the past, and it uses that power in a benign if sometimes heavy-handed fashion. It brings to mind a line of Thomas Jefferson’s, written in a much different context: “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” But liberty, a least as manifest as modern South Korean democracy, is an unusual beast, not subject to the constraints that apply elsewhere; its self-described ultra-patriots end up portrayed as thuggish, unsympathetic villains in the movies; and at least in the case of Chun Doo-hwan, the general-turned-president whose blankly stern visage glares down from the walls of all the office sets in the film, the tyrant lives on, undisturbed and behind police guard, just about a mile from the gates of Yonsei University.

Related Korea Blog posts:

As Detroit Shows Americans an American Riot, A Taxi Driver Shows Koreans a Korean Massacre

From Language Lessons to Sex Slavery: Korea’s New Comfort-Woman Comedy I Can Speak

An Ajeossi and His Robot (or, How Korean Film Dramatizes Disaster)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.