Koreans hate Japan. Even those who know precious little else about Korea — that place with the spicy food, all that pop music, and the troublesome neighbor? — know that. But in recent years public expressions of anti-Japanese sentiment have been hard to come by here, at least from the under-80 set. Any outside observer might rightfully have asked, do Koreans really hate Japan? When the last generation to remember suffering under Japanese colonial rule passes on, won’t the bad blood dry up entirely? But the past few weeks have breathed new life into Korean resentment against Japan, a feeling that culminated in a protest march through downtown Seoul last Thursday — very much not coincidentally National Liberation Day, when Koreans, both South and North, celebrate Japan’s defeat in the Second World War.

I say “the past few weeks” because I’ve only been in Korea that long, having spent the month and a half before that in the West. Even when I’m out of Korea I make sure to keep up with Korean news, and from it I got the sense that a rumored “trade war” with Japan had grown into a fairly serious matter. Few other stories got much airtime on the television screens on the train back into Seoul from Incheon Airport — a train whose walls were also lined with advertisements for a newly launched Korean budget airline and its many Japanese destination cities. When I got back to my neighborhood, I saw anti-Japan posters here and there along the streets, and even a group of identically dressed college students doing dance routines in favor of boycotts against the country. But it can only have made actual Japanese people in Seoul so uncomfortable, since quite a few of the voices I heard as I made my way home were speaking Japanese.

My first serious thought about all this was a thought shared by many an apolitical Korean: I should see if there’s a sale on at Uniqlo. The Japanese clothing chain has become one of the most visible businesses at which Japan-boycotting Korean consumers have refused to spend money. So have the high-design household-goods retailer Muji, the discount shop Daiso, and even 7-Eleven, whose prevalence in Japan has caused some to mistake it for a Japanese brand. Japan has also seen a drop in tourism from Korea, on top of the loss caused by the belief (uncommon in the rest of the developed world) that the whole country has been dangerously radioactive since the Fukushima Daiichi power plant disaster of 2011. Pictures of signs denying Japanese customers entry to Korean businesses have circulated on social media. And a middle-aged man went viral by smashing up his own Lexus on video, shouting about his embarrassment at owning a Japanese car.

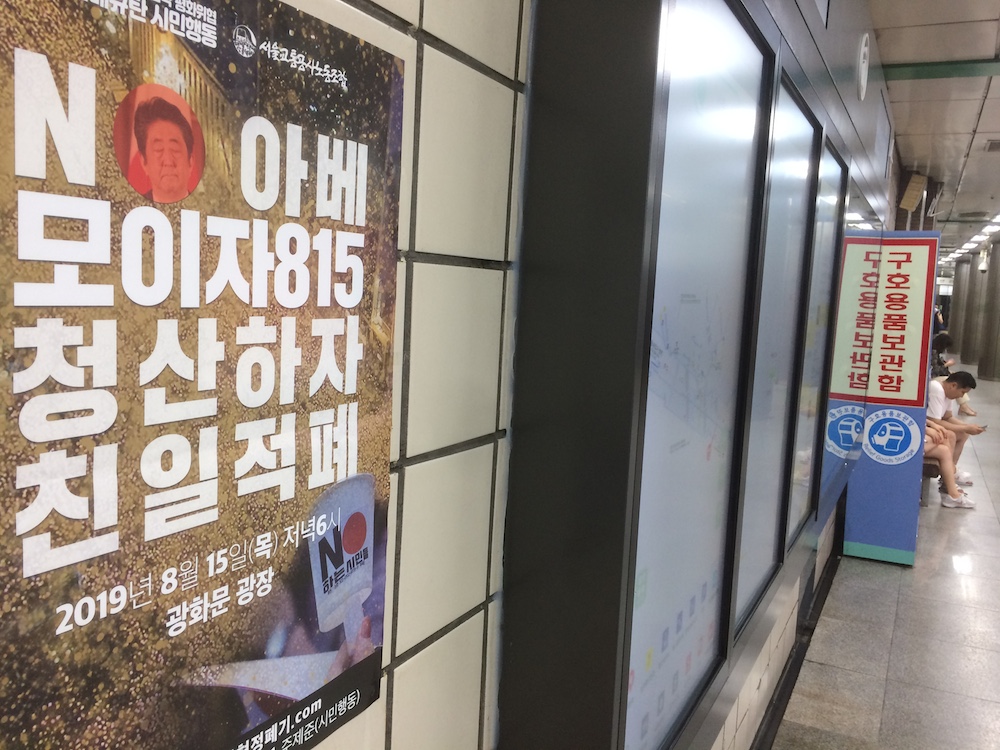

What caused this flare-up? The most commonly told story blames Japan’s removal of South Korea from its list of preferential trading partners. Citing vague North Korea-related national security concerns, it clamped down on the exportation of several chemicals Korea’s giant electronics companies rely upon to manufacture top exports like semiconductors and displays. Korean observers have framed that decision as an “economic invasion,” a “weaponizing of trade” by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe. Some stress that the target of this anger isn’t the Japanese people, and isn’t even the nation of Japan per se, but Abe in particular. Many of the posters, banners, and leaflets put up around Seoul stress that point, putting his picture alongside messages like “No Abe” (the O typically in the form of a Japanese flag-style red circle with Abe’s face inside) or even “Japan, murderer.” The boycott is intended to show Abe the error of his ways.

In this reading of the situation, Abe not only fears his country being overtaken by Korea in the key industries it once dominated, but being left out of a peace agreement with North Korea as well. There is also the element of retaliation, in this case for two Japanese corporations being ordered by Korea’s Supreme Court to pay reparations to Koreans forced into labor during the colonial era — an entirely separate issue from that of the “comfort women” put into sexual servitude during the war, which has naturally received even more attention than usual lately. But from the perspective of official Japan, those debts were already paid by the $500 million it gave Korea back in 1965, and in any case no apology to Korea, no matter how formal, ever seems to satisfy it. And would even the most dedicated Korean participant in the boycott deny that emotionally charged historical grievances play as much of a role here as national security and trade disputes?

Still, the true extent of this latest wave of anti-Japanese sentiment wasn’t easy to gauge until the Liberation Day protests put it to the test. A million people in the streets, the kind of number that turned to demand the resignation of Park Geun-hye, would surely provide President Moon Jae-in with the mandate to prosecute this trade war further. Despite the summer humidity, it surely seemed possible, and with all the patriotic songs on the radio from morning onward, the mood certainly seemed right. But though Korea’s culture and tradition (and, it must be said, industry) of protest always makes these demonstrations sights worth beholding, this one fell undeniably short of expectations. People turned up with their candles and “No Abe” signs, but nowhere near a million of them, and as often in Korean protests, a variety of other causes turned up and muddied the waters: the pro-unification protesters; the anti-Moon, pro-Park protesters; the pro-Trump, pro US-alliance protesters; and even a few bold souls shouting the equivalent of “Abe forever!”

The casual Western observer will have a number of questions about all this. What, exactly, is the point of all this squabbling between Korea and Japan, given the two countries’ economic interdependence (the Japanese chemicals that go into the Korean-made electronic components, for instance, often go right back into Japanese products, many of which are, or at least were, exported back to Korea) and the rapid rise of China over their shoulders? If a serious disruption of the global supply chain results, will the United States, which has heretofore shown little interest in the matter, be forced to step in? How far can Korea possibly push this boycott — to the point of the Tokyo Olympics next year, for which its star athletes have spent years training? How did Japan become the bad guy instead of North Korea? And what stops Korea and Japan, which on the surface seem so well-placed for cooperation, from working together?

But then, Korea and Japan working together, as a journalist friend based in the latter country once put it, is as hard to imagine as the Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers working together, so deep does the incompatibility run. And a Korea without anti-Japanese sentiment may not be Korea at all, at least according to the view that outward resentment toward Japan (“Koreans hate Japan”) is one of the few common threads holding this otherwise fractious society together. In that sense, these protests encourage a kind of national cohesion, but would they be as necessary if Koreans could get on the same page about the history of their country, a subject whose shifting sands have proven treacherous for politicians and academics alike? Watching the Liberation Day protest, I thought of the very first demonstration I saw in Korea, whose suite of issues included the latest proposed revision of history textbooks by the Park Geun-hye government. If a nation is defined as a people who, broadly speaking, agree on their history, what does that say about South Korea as a nation?

Perhaps this is to be expected from a nation-state whose history still doesn’t go back particularly far. And whatever the disappointments of the Liberation Day parade for the anti-Japanese die-hards, as an outsider — indeed, as an American — I look with admiration on any step, however tentative, Korea takes outside the security envelope of the United States. To Japan, and often to the rest of the world, Korea appears obsessed with the past, but the richer questions are about its future: what kind of country will Korea become, for example, in a world no longer consolidated under a single order, a world in which it may have to guarantee its own security? Accustomed to a position of weakness, Korea takes pride in its developmental accomplishments, but not the kind that that translates into an understanding of its no-longer-weak position in the world. The longer I live here, the more I wonder: what will this country be like when it finally knows its own strength?

Related Korea Blog posts:

Anti-Trump Protests, Anti-Park Protests, and the Koreanization of American Politics

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.