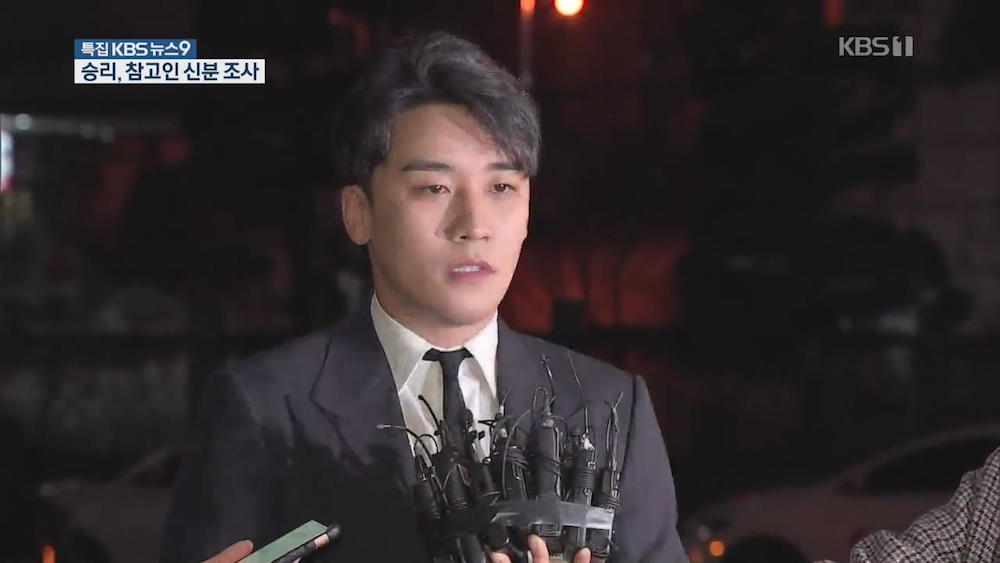

However robust the Korean supply of public apology has been lately, it may never even come close to meeting the Korean demand for public apology. Longtime Korea observers know this, just as they know that the apologies, and more so the expectations for and rejections of those apologies, have only just begun to flow forth from the Burning Sun scandal. What began as a possible case of sexual assault at a Seoul nightclub of that name last November has, over the past few months, blown up to encompass drugs, embezzlement, prostitution, police corruption, and hidden-camera sex footage rings. This increasingly complicated affair has drawn such rapt public attention not least because of the identity of one of Burning Sun’s managers: Lee Seung-hyun, better known as Seungri, a member of top boy band Big Bang.

“I sincerely apologize to everyone who has been involved in or taken offense from the recent controversy,” Seungri posted to Instagram in February. “I am sorry that this official explanation and apology is overdue. Surrounding acquaintances have discouraged me from apologizing right away, lest the uncertain details that have already snowballed create even bigger misunderstandings.” But it seems that even apologizing on one of the most popular social-media platforms in Korea (and later in concert) wasn’t enough to save him: first he was suspected of ordering the procurement of prostitutes for the nightclub’s clients, then his agency YG Entertainment terminated his contract, then the police charged him with distributing a picture taken with a hidden camera, then they charged him with embezzlement, and the dirt is apparently still being dug up.

Seungri isn’t the only celebrity brought low by the Burning Sun investigation so far: trawling the group chat rooms shared by these K-pop stars on Kakaotalk, Korea’s messaging app of choice, the dragnet has also ensnared, among others, the singer Jung Joon-young, who had used those rooms to distribute his own sex videos. “I admit to all my crimes,” says Jung’s statement of apology. “I filmed women without their consent and shared it in a chat room, and while I was doing so I didn’t feel a great sense of guilt.” It goes on: “Most of all, I kneel down to apologize to the women who appear in the videos and all those who might be disappointed and upset at this shocking incident,” adding an intent to “repent for my unethical and unlawful behaviors, which constitute criminal acts, for the rest of my life.” But neither those words nor any others are likely to put his image on the road to rehabilitation.

The fierce public reaction brings to mind the hacking of Sony Pictures and subsequent leaking of its internal emails a few years ago (which happened to have Korean connections of its own). That brought to light nothing more distasteful than “the vocabulary, personal ethics, and racial nicety of leading film producers,” as the New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane put it, come though it did as an “unbearable shock to those of us who have always confused them with Franciscan friars.” What, exactly, did all the Koreans stunned by the Burning Sun revelations (who have by now surely deleted all of the songs they’d downloaded by Roy Kim, another singer more recently implicated in the non-consensual video-sharing) thought a bunch of twentysomethings get up to when granted the kind of wealth and social status accorded to the likes of Jung and Seungri? It hardly surprised me that another participant in those Kakaotalk rooms summed it up this way: “Our lives are like a movie. We have done so many things that could put us in jail. We just haven’t killed anyone.”

Does the Korean public react the way it does to scandals like these out of pure naïveté, or are there more complex motivations at work? Might it know full well what its celebrities, policemen (some of whom may have colluded with Burning Sun), and politicians do behind closed doors (or in private chat rooms), but only feel compelled to get incensed about it when media coverage brings an instance of it to national — or much worse, international — attention? Could the driving force have less to do with moral outrage than the need to visibly put oneself on the right side of the issue, and at the greatest distance from those who have been declared wrong? The latter, typically, vehemently deny the charges against them as long as they can, but sooner or later reach the point where all they do is give in to the calls for a display of contrition, even self-abasement. And even then the public can, and often does, find their apologies lacking in “sincerity.”

The same phenomenon occurs in dealing with matters of historical importance as well. The thickening of the Burning Sun plot mostly overshadowed the 71st anniversary of the Jeju Incident, the armed revolt by the Workers’ Party of Southern Korea on April 3, 1948 that led to the killing of more than 10,000 civilians by South Korean security forces over the following six years. Presidents have apologized for the massacre on previous anniversaries, but this year’s brought an unprecedented apology by the commissioner general of the Korean National Police Agency. Or at least it brought his expression “deep regret,” and the difference between that and a full-blown apology has not been lost on the Korean press, let alone the matter of how sincerely he delivered it.

The question of sincerity has come up time and time again as regards the now well-known issue of Korean “comfort women” drafted into sexual servitude for the Japanese military during the Second World War. In Korea one occasionally hears that Japan has never apologized for anything, let alone that, an assertion that would seem to be given the lie by, say, Wikipedia’s list of war apology statements issued by Japan. The problem turns out to be that none of Japan’s apologies have been widely taken as sufficiently sincere, a difference of perception that hints at the vast cultural divide beneath: whereas in Japan adherence to the form of an interaction is everything, Korea sets great store by the involvement of the sokmaeum, or “heart of hearts.” (Many Koreans who go to live in Japan come back complaining, even if they enjoyed everything else about it, that they could never understand the sokmaeum of the Japanese people.) But could anything said by a representative of Korea’s former colonizer, no matter how contrite, even theoretically put an end to the accusations of insincerity?

“Considering people who have fallen from grace,” writes Ian Buruma in a recent Financial Times piece, “it is hard to avoid using religious language. The way out of moral ignominy is to be redeemed. But redemption has to be earned by confession, self-reflection and apology. This is why people caught in a history of sexual misbehavior usually issue an apology straight away, sometimes a rather slippery one: ‘If I have offended anyone…,’ etc.” Korean public apologies make use of similarly evasive tactics, the equivalent of “what happened is regrettable” being an especially common rhetorical ploy. Buruma takes on this subject because of the experience last year that ended his short time as the editor of the New York Review of Books: the backlash to his running “Reflections from a Hashtag,” an essay by Jian Ghomeshi, the CBC host taken to court on sexual assault charges in 2016. “I was only an offender by proxy, as it were. Nonetheless, I was strongly advised by a senior editor at a famous liberal journal in New York (not the NYRB) to write an apology, so that his ‘younger editors’ would allow me to contribute to that magazine again.”

Buruma ultimately decided against apologizing because “apologies are the traditional reaction to a moral transgression, when grievous offense is taken. One reason that apologies are now so prevalent is that being offended has become a common reaction to anything one disagrees with. This can pose particular difficulties for an editor of a liberal journal.” And “apologies are not always enough to end social and professional ostracism. Which is perhaps why they play only a small part in western law. Sanctions have to be more sharply defined and have distinct limits. The demand for apologies in our present culture has more in common with the way law is practiced in East Asian countries, with a Confucian tradition, where apologies play a major role, as do written confessions. It is not enough to be materially penalized; the accused has to prove that he or she has repented. An inner transformation is called for.”

In this way, the realms of Western media and public opinion have come to resemble Korea over the past few years. Germany may be less flooded than the United States with this newfound zeal for sincere apology and inner transformation, but there the gardening store Hornbach now finds itself subject to demands for apology over a video ad that has made its way across the internet. The offending spot, “The Smell of Spring,” shows a series of burly, sweaty German men working outside. Lab-coated professionals appear to collect their soiled clothing, which we then see vacuum-packed and stocked in a vending machine on the streets of a generically gray, dystopian Asian metropolis. A woman approaches the machine, makes her selection, then feverishly tears open her purchase and huffs the air from inside the package, her eyes rolling back in ecstasy.

The joke here seems to be a reversal of the old image of the Japanese salaryman who gets his kicks buying used schoolgirls’ underwear from vending machines, but whatever the effectiveness of the humor, it got Hornbach promptly accused of simultaneous racism and sexism. Coverage of the controversy quotes one Korean Twitter uses as claiming that “the Asian woman is represented as a mere tool to make the white male customers feel better about themselves” and another asking the store, “How many more Asian female voices will you need to take us seriously and be aware of your thoughtless deeds and apologize?” The hashtag #Ich_wurde_gehornbacht (“I was Hornbached”) has emerged, as has an online petition to pressure Hornbach into an apology for its “extremely problematic” representation of an Asian woman that, as of this writing, has collected more that 30,000 signatures. But the company has stood firm: “Our ad is not racist,” it replied to one of its Korean accusers on Twitter. “View the ad as a discourse on the increasing urbanization and decreasing quality of life in cities.”

Koreans quoted in the press have not found that explanation convincing. “Many Asians experiencing sexism and racism in Germany are voicing their thoughts and concerns, and criticizing the much misguided #hornbach ad but you are ignoring us and denying our experiences, as if you would know better,” tweeted one. “The ad was sexist, racist, fetishized East Asian women, and now they are trying to talk their way out of it?” tweeted another. Perhaps it’s the Hornbachs of the world who are naïve, uncomprehending as they are of the reality that has long obtained in Korea and is now taking hold elsewhere: once the public decides you have something to apologize for, there is no viable response. Even if you submit to paying out the apologies demanded, the currency has been too debased to settle the perceived debt. Best, in the case of Seungri and his Burning Sun cohort, to let the machinery of justice do its work. Everyone else might consider bearing in mind “Never apologize, never explain,” a variously attributed proverb now in danger of being utterly forgotten.

Related Korea Blog posts:

The #MeToo-ing of Ko Un, Korea’s Best Hope for a Nobel Prize

Anti-Trump Protests, Anti-Park Protests, and the Koreanization of American Politics

From Language Lessons to Sex Slavery: Korea’s New Comfort-Woman Comedy I Can Speak

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.