When a Korean wins a major international award, that award tends to be seen here in Korea as having been won for, or even by, the nation itself. Olympic gold medals, if not silver or bronze, have long mattered a great deal. Anticipation for another Nobel has run high since former president Kim Dae-jung’s Peace Price in 2000. The 2016 Man Booker International Prize went to novelist Han Kang and her English translator Deborah Smith for The Vegetarian, but in the eyes of much of the press here, the validating honor also went to Korean literature itself. Over the past decade or two, Korean film has enjoyed a higher global profile than many other products of Korean culture, but no Korean filmmaker had ever come back from Cannes with a Palme d’Or. Or rather, none ever had until last week, when Korea — or rather, Bong Joon-ho — won it with Parasite (기생충).

Cinephiles may wonder what took the Cannes jury so long to bestow the Palme d’Or upon a Korean film, given the astuteness the festival has shown in regard to Asian cinema in general: they gave one to Thai auteur Apichatpong Weerasethakul‘s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives in 2010 and have given five to Japanese pictures over the past 65 years, most recently Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Shoplifters in 2018. That film, about a poor but cheerful quasi-family clinging to the margins of modern Japanese society through a life of small-time crime, has more than a little in common with Parasite, which tells the story of a father, mother, son, and daughter living by their wits in the closest thing to a Seoul slum a mainstream movie has dared portray. Earning a meager income by folding cardboard pizza boxes, the Kim family may not have to shoplift — not regularly, at least — but they do have to live by their wits, seizing upon any and all minor opportunities that present themselves just as they do the unprotected wi-fi signals that reach the corners of their run-down basement apartment.

The Kims occupy roughly the same level of socioeconomic desperation as Jong-su, the young protagonist of last year’s Burning (버닝), an adaptation of a Murakami Haruki short story by Lee Chang-dong, a Korean filmmaker even more critically respected than Bong Joon-ho. But audiences here and elsewhere may have felt a little too discomfited by the stark, paranoid vision of that film — which lost the Palme d’Or to Shoplifters and which I recently heard Lee himself describe as having manghesseo (망했어), or bombed — whereas their reaction to Bong’s new movie, at least since it opened here last week, has been nothing but enthusiastic. The domestic press also describes it as a kind of homecoming, even the return of a prodigal son, given that Bong made his last two pictures, both big-budget spectacles, mostly in the West: 2013’s French graphic-novel adaptation Snowpiercer, which drew raves but evidenced little connection to Korean cinema, and 2017’s Okja, a half-Korean and half-Western fable of a girl and her enormous genetically modified pig.

Parasite thus comes as Bong’s first wholly “Korean movie” in ten years, but though its action never leaves Seoul and its cast includes no major foreign characters, it nevertheless retains a deep thematic concern with the West. In this it shares another similarity with Burning, which confronts Jong-su with an unsettlingly benevolent romantic rival possessed of not just considerable wealth and an elegantly appointed Gangnam apartment but a host of vaguely foreign attitudes and mannerisms as well. Parasite visualizes more explicitly the idea that the richer Koreans become, they more they turn into grotesque parodies of Westerners. Up the hill from the Kims — way up the hill from the Kims — lives another family of four, the father a tech millionaire called “Nathan Park” by the Western magazine covers on which he appears, the mother a vacuously anxious education obsessive who peppers her speech with English phrases as ostentatious as they are awkward.

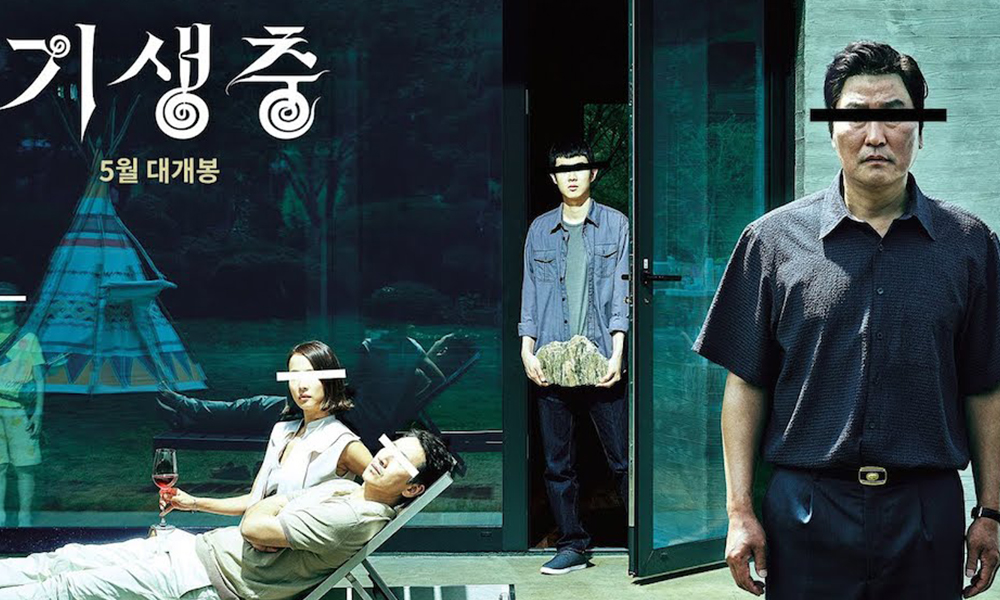

The Parks live in a gated home designed in concrete, glass, and wood by a famous modernist architect, with a Mercedes and Range Rover in the garage and VOSS water in the refrigerator. The Kims first gain access to this house when their son Ki-woo shows up to tutor the Parks’ daughter in English, having taken over the job over from a friend who has departed for America. This demands that Ki-woo fake not only knowledge of English but a diploma from a prestigious university, which his sister Ki-jung whips up for him in Photoshop. Soon Ki-woo, who has introduced himself in the Park residence as “Kevin,” has also brought Ki-jung into the household’s employ as “Jessica,” an art-therapy teacher for the Parks’ American Indian-obsessed young son. With increasingly underhanded methods, the Kim siblings arrange for the replacement of the Parks’ housekeeper and chauffeur by their own mother and father, Chung-sook and Ki-taek.

Plot summary makes obvious the question implied by the film’s title: who, exactly, is the parasite? The Parks, who live in luxury without making much in the way of a contribution to the world around them, or rather below them? The Kims, who literally attach themselves to the Parks and feed off their wealth? The people below even the Kims, those who exist almost unseen at the very bottom of Korean society? Parasite ultimately looks to lower depths, literally as well as figuratively, than its publicity suggests, and Bong himself made a Crying Game-style plea to the reviewers at Cannes not to reveal to the public what the film finds there. It would be impossible to imagine Lee Chang-dong expressing such concern over spoilers, but for Bong it’s more or less characteristic, as are the jump scares, slapstick gags, and stretches of suspense, and elaborate set pieces that lead up to Parasite‘s final, impulsive, and cathartic act of violence — one that bears a striking resemblance to the final, impulsive, and cathartic act of violence that ends Burning.

Bong has tended to draw comparisons to Steven Spielberg, but Parasite may well get him seen as a kindred spirit of a younger American filmmaker, and one whose sensibility contrasts starkly with Spielberg’s: Jordan Peele, whose recent satirical horror pictures Get Out and Us have won such disproportionately great popularity in Korea that the director got more than 4,000 retweets just by posting his own name in Korean. Peele’s willingness to mix the conventions of various genres in a single film will feel familiar to anyone who has spent time with recent Korean cinema, and especially with Bong’s contributions to it. So will his inclination toward broad social criticism, though a Westerner unfamiliar with the viewing tastes of the Korean public may wonder what audiences here see in Peele’s pointed stories of black Americans trapped in benign-seeming surroundings that turn lethally hostile.

But there does exist in Korea a strong taste for stories of America’s troubled race relations, going back at least as far as the 1992 Los Angeles riots, and the more intractable the trouble the better. Korean viewers may watch movies that tell such stories and feel a certain satisfaction, justified or not, that though they may have grown up believing their homeland inferior in every way to the United States of America, at least their people aren’t subject to the kind of apparently deep and explosive animus that exists between black and white. But those same viewers can’t get enough cinematic critiques of the class divide in Korea, made in much the same tone as those critiques of the race divide in America. Just as in Peele’s films, Parasite doesn’t end well for any of its characters, even those who somehow survive the bloody final act. At least the Parks’ magnificent house, the one the Kims so bitterly covet, makes it through unscathed — though it ends up occupied not by the rich Koreans, nor by the poor Koreans, but by Westerners.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Burning: an Acclaimed Korean Auteur’s Explosive, Haruki Murakami-Adapting Indictment of Inequality

Wangsimni, My Hometown: a Gangster (and a Filmmaker’s) Pledge of Devotion to Korea

Korea’s English Fever, or English Cancer?

Korea Has Started Using English Names — But When Will It Stop?

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.