This is one in a series of essays on important pieces of Korean cinema freely available on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel. You can watch this month’s movie here and find links to previously featured movies below.

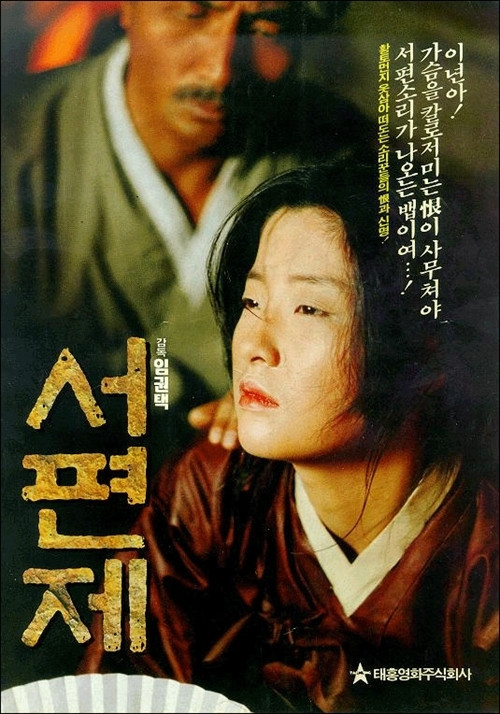

One singer and one drummer on an otherwise nearly bare stage, expressing the pain of Korea for four or five hours: the prospect, to a great many foreigners, does not immediately appeal. Then again, despite its deep roots in the culture, the traditional form of musical storytelling called pansori (판소리) didn’t much appeal to a great many Koreans for a long stretch of the twentieth century, if not due to distaste then to unfamiliarity. But “Korea’s opera” has seen a revival of interest in recent decades, due in part to the massive success in 1993 of a movie about, and only about, the then seemingly dying art and the emotion that drives it: Im Kwon-taek’s Seopyeonje (서편제).

The prolific Im, still working today after 102 films and counting, directed in the first years of the 1990s a trilogy of popular gangster pictures, General’s Son (장군의 아들) and its two sequels. (You can watch the first of them on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel, as well as Im’s 1976 Wangsimni, My Hometown, the last movie we featured in this series.) Their considerable box-office return gave him a free hand to make a passion project, and on paper Seopyeonje looks like the very definition of one: a middle-aged filmmaker who remembers a very different time in his rapidly developing homeland tells a story, in the form of a period piece within a period piece, of a wandering pansori master and his two young charges whom history has already left behind, but whose suffering only enriches the tradition to which they have dedicated their lives.

That suffering produces an emotion much written about as unique to the Korean people: han (한, often written with the Chinese character 恨), variously explained in English as “lifelong regret,” “a collective feeling of oppression and isolation in the face of insurmountable odds” connoting “aspects of lament and unavenged injustice,” the “sentiment that one develops when one cannot or is not allowed to express feelings of oppression, alienation, or exploitation because one is trapped in an unequal power relationship,” and an “acute pain in one’s guts and bowels, making the whole body writhe and squirm, and an obstinate urge to take revenge and to right the wrong.” Fictional United States President Josiah Bartlet, on the episode of The West Wing when he has to turn away a North Korean asylum-seeker, explains it as “a sadness so deep no tears will come. And yet still there’s hope.”

Scholars of han ascribe it to a variety of conditions of Korean life and history: the legacy of the rigid class system within the country, its geographical position in the midst of much stronger powers, the frequency of its invasion by those powers, and its current division into North and South. Some critics find han expressed in every single Korean art form, traditional or modern, though to global audiences it probably comes through most vividly in Korean film, which enjoyed its international boom at the turn of the twenty-first century. “Young South Korean directors like edgy stories of violence and sex.” wrote Time‘s Hannah Beech in a 2002 profile of Im, a director “of a more mature school, preferring graceful period pieces, produced with Akira Kurosawa-style attention to costume and scenery and marked by a peculiarly Korean form of sadness called han.”

Beech wrote of Im’s “worries that han and other cornerstones of the modern Korean ethos are slipping away as the nation speeds into the Internet age and replaces wooden temples with concrete office blocks,” quoting him on his country as his subject (“Every one of my bones is Korean. How can I make movies about anything else?”) as well as — seldom absent in Korea, then or now — his didactic ambitions: “My goal for making movies is to teach the world about Korea. But I also want to teach my own countrymen about their own history.” At the time of the profile’s publication, one could still assume a general Western ignorance of things Korean (Im was “often met overseas with polite, confused smiles that say: Oh, Korea has a modern film industry?”), but South Korea’s unrelenting, imitative modernization throughout the second half of the twentieth century, which followed a decades of Japanese colonialism and a devastating war, had also left many Koreans, especially the younger generations, not much better versed in their own culture.

Seopyeonje rushed into that very knowledge vacuum, satisfying some of the yearning it produced while starting from a sparsely attended single-screen opening to become, over a run that lasted six months, the most popular Korean film to that point in history, selling a million tickets in Seoul alone. The reason it became such an unexpected phenomenon must have had to do not just with its educational value of reintroducing elements of a culture and identity with which audiences felt they’d lost touch, but of presenting an image of Korea’s virtues that matched what ideas of them remained: endurance, emotiveness, a certain bloodymindedness, and the combination of rawness and refinement that, though expressed most strikingly in pansori, manifests in countless other aspects of Korean life and art as well.

It also showcases Korea’s “four distinct seasons,” a quality of debatable uniqueness but one still widely used in the promotional literature today. (Kim Ki-duk, though a filmmaker possessed of a starkly different sensibility from Im’s, also exploited it ten years later, to great acclaim, with Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring, which came out just as Korean cinema’s international popularity hit a new level.) The film’s elemental qualities come out in every sequence, especially those in which the characters traverse, on foot, the Korean countryside, against the wind, under the sun, and finally through the snow, the first of which shows us a family, of a kind: a man, a woman, and two small children.

The traveling pansori singer Yu-bong has convinced his widowed lover to leave her hometown and the shame of her situation behind, and with them the woman’s son Dong-ho, and Yu-bong’s “daughter” Song-hwa, an orphan he has adopted in order to raise as his artistic continuation. But Dong-ho’s mother soon dies in childbirth, reducing the group to three, and in the single five-minute take which remains the film’s most remarked-upon shot, they appear in the distance at the end of a winding country road and approach singing “Jindo Arirang,” a version of the folk song that has become Korea’s unofficial national anthem from the southwestern Jeolla provinces, Seopyeonje‘s setting as well as Im’s birthplace. This straightforwardly happiest scene in the film expresses another emotion proposed as distinctively Korean: heung (흥), a kind of spontaneous collective joy.

“The singers slowly dance toward the camera, but the camera doesn’t move” the University of Nottingham’s Julian Stringer writes of this shot in his essay “Seopyeonje and National Culture.” “The sound mix doesn’t vary either. No matter where the three characters are on the road, we can hear their voices loud and clear,” as we can hear those voices “echoing around the sound booth.” Deliberate or not, this spatial sonic mismatch hearkens back to an earlier Korean cinema, all of whose dialogue was recorded not on set but later, in facilities of varying quality, and then added back in editing. It imbues the film’s walking pansori performances with the same uncanny resonance of words spoken outdoors in Korean films of the 1950s and 60s.

The film’s first scenes, in fact, take place in roughly that era. A grown Dong-ho, having abandoned the rigorous austerity of life under Yu-bong in adolescence, turns up in a village in search of Song-hwa. In a tavern, he finds not his long-lost quasi-sister but another pansori singer who learned the art from her, and who fills him in on her story: “After mourning her father’s death for three years, she left. I am worried about her because she’s blind. Some people say her father made her blind to make her sing better. Some say he made her blind to stop her from leaving him. But others say that no father in this world would make his daughter blind to make her stay behind. He did to inflict great sorrow into her heart so that she could sing well.”

In this view, technical mastery, no matter how focused, can only take a pansori singer so far; to express the music’s sorrow, she must live that sorrow. And that singer should, ideally, be a she rather than a he: though male pansori singers like Yu-bong did and do exist, they more often handle the drum accompaniment and only occasional vocalizations as Dong-ho does, leaving the rest to the sex historically regarded in Korea as, in some sense, the living embodiment of suffering itself. This backward-looking, allegorical film has in the near quarter-century since its release drawn predictable critical accusations of glorifying the very patriarchy that inflicted that suffering, some that go as far as to read it as an approving story of the lengths to which a father can go — binding her to a tradition, stripping her of her ability not just to choose but to see — in order to limit his daughter’s sexuality.

Seopyeonje‘s final shot shows us another instance, in slow-motion, of what we’ve seen several times before: figures walking through a Korean landscape. First they were Yu-bong, Song-hwa, Dong-ho, and Dong-ho’s mother; then Yu-bong, Song-hwa, and Dong-ho; then just the sightless Song-hwa trailing Yu-bong on a lead. Now Song-hwa has become the elder, and in front of her walks a young girl the film never properly introduces. Whether daughter, disciple, or something in between, her existence gives Song-hwa a means of moving on from her circumstances, continuing her seemingly endless migration through the countryside, the last of the film’s pansori singers still standing and still devoted to the art as modernity descends around her. She has triumphed in a way that, despite its tragic edge — or indeed because of it — resonated with millions of viewers around whom modernity had descended much more thoroughly still.

Related Korea Blog Posts:

Wangsimni, My Hometown: a Gangster (and a Filmmaker’s) Pledge of Devotion to Korea

Watching Madame Freedom, the Movie that Scandalized Postwar Korea

The Unbearable Preposterousness of Westernization: Park Kwang-su’s Chil-su and Man-su

Between Boring Heaven and Exciting Hell: Kim Soo-yong’s Night Journey

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.