If you watched even a few clips of televised celebrations from countries around the world this past New Year’s Eve, you almost certainly saw South Korea’s. Each year at the stroke of midnight, a group of notables together commence the traditional ringing of Bosingak, the large bell in downtown Seoul used to announce the opening and closing of the city’s gates in centuries past. Those who follow baseball may have recognized among this year’s bell-ringers Ryu Hyun-jin, currently of the Toronto Blue Jays and formerly of the Dodgers. Those who follow the European Union may have recognized its ambassador to the Republic of Korea Michael Reiterer. But to most Korean viewers, especially those personally thronged around Bosingak in the freezing cold, one face jumped out before all others: that of an aspiring “universal superstar” named Pengsoo.

Then again, Pengsoo’s face probably jumped out at viewers regardless of their nationality, belonging as it does to a nearly seven-foot-tall penguin with headphones. Despite having never been seen nor heard of at the beginning of 2019, Pengsoo had by the end of 2019 become enough of a cultural phenomenon to appear alongside the mayor of Seoul on international television. This makes it a natural if show-stealing figure to ring out the old year and ring in the new — “it” being the most suitable pronoun available, what with the character’s clearly documented state of genderlessness. That’s just one of the qualities that sets Pengsoo apart from the countless anthropomorphic animals that daily cavort across Korea’s media landscape: the others include a penchant for dropping honorifics and an undisguised hunger for fame.

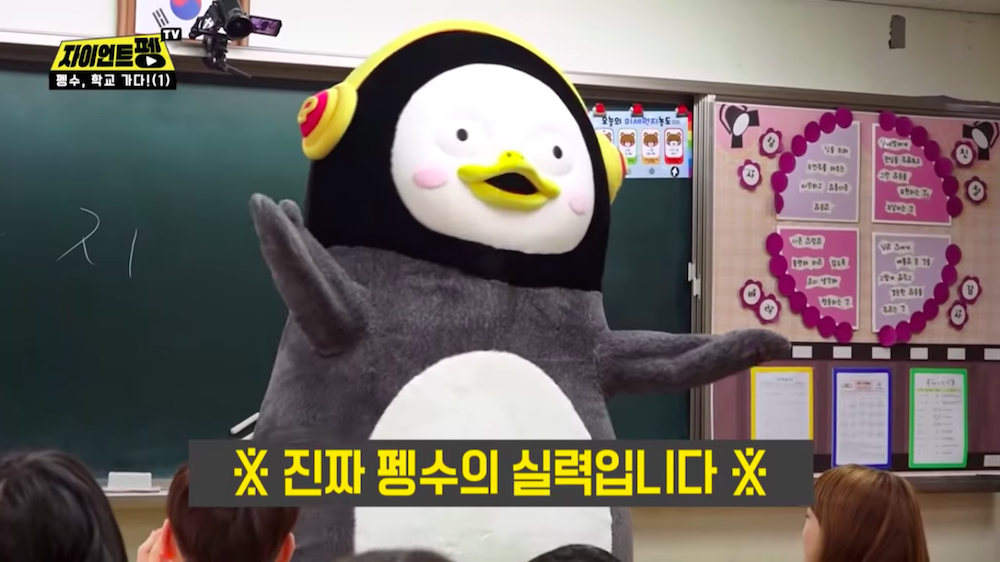

Despite being eternally 10 years old (while speaking in a voice more like that of a grumpy middle-aged man), Pengsoo is obviously not in the business of setting an example. Still, it did begin its journey to fame in an elementary-school classroom, having been sent there to begin accumulating fans by the Educational Broadcasting System (EBS), the television network that ostensibly employs it as a trainee. The first episode of Pengsoo’s Youtube series Giant Peng TV (자이언트 펭TV) documents this visit, which ends with the titular giant penguin declaring his bold intention to become more popular than a little penguin: the aviator-helmeted, bespectacled Pororo, Korea’s best-loved character for children since his debut in 2003.

That competition can only get so serious, since both Pengsoo and Pororo are property of EBS. Pengsoo joins a roster that includes not just Pororo but also characters like Tayo the Little Bus, that four-wheeled and two-eyed provider of lessons in friendship, courage, and public-transit etiquette. Others, like a gaseous humanoid persimmon named Fart General Poong-poong-i, would seem to offer somewhat less in the way of educational value. Pengsoo proudly offers none at all, having few stated concerns beyond advancing its own fame. Back in April or May of last year, when almost nobody knew the name of Pengsoo and not many more subscribed to its channel, it worked a vehicle for satirizing the delusions of Korea’s herd upon herd of Youtube-based self-promoters (a phenomenon especially pronounced in this country, but hardly limited to it). But now, whether intended to or not, Pengsoo has become genuinely famous.

Pengsoo’s constant calls to subscribe have, as of this writing, induced more than 500,000 people to follow its Instagram and 1.8 million to follow Giant Peng TV. Those figures surely include many more adults than children, the initial promotion of Pengsoo to Koreans of its own “age” notwithstanding. Though designed firmly in the tradition of child-oriented characters in Korea and across Asia — firmly enough to draw accusations of being nothing more than an outsized Pororo clone — it seems to have gained greatest cultural attraction among working men and women who may harbor their own fantasies of behaving in a Pengsoo-like manner. Having literally made its home in the headquarters of its employer (at first setting up camp between the shelves of a supply room), Pengsoo nevertheless acts according to its impulses and with total impunity, disregarding the professional and social strictures that bind the EBS employees around him (up to and including head of the network Kim Myeong-joong, whose name Pengsoo has made well known) who do what they can to interpret its desires and rein in its excesses.

Maybe Pengsoo gets a pass for being a penguin — at least since one episode settled, with the aid of a veterinary x-ray machine, the controversy of whether it was indeed a penguin. But it’s also a foreign penguin, and thus like all foreigners less subject to the expectations of Korean society; with no formal place in the system, it in certain ways transcends the system, especially when it comes to talking back to superiors. More than once Pengsoo has told the story of its journey to Korea from its homeland in Antarctica, interrupted only by a sojourn in Switzerland where it learned to yodel. (I haven’t seen whether it has ever explained how it acquired fluent Korean in less than a year, but the rest of us foreigners would certainly like to know.) Yodeling isn’t a skill entirely irrelevant to its larger mission of attaining Youtube fame and becoming a world-class keurieiteo, though what, exactly, it creates is beside the point.

Pengsoo has no particular expertise, but it does sing, dance, crack jokes, eat tuna out of the can, and try out a variety of professional roles for which it isn’t prepared. Over the past few months, Youtube-viewing Koreans have so enjoyed watching Pengsoo do these things as it attempts to live among humans that it has begun to pop up with impressive frequency elsewhere: on the broadcasts of other television networks, in advertisements (often, in my experience, the commercial Youtube runs before a Pengsoo video also features Pengsoo), and even on growing range of merchandise bearing its impassive, Sticky Monster-like mupyojeong. (Its constant use of old-school over-the-head earphones may well put a dent in Koreans’ startlingly widespread adoption of Apple AirPods, or more often their Samsung equivalent.) Pengsoo will no doubt have its time as a trend, but most trends in modern Korea, in the manner of the London Review of Books tote bags of a couple years ago, all but vanish nearly as soon as they appear.

Still, Pengsoo has already proven an uncommonly reliable source of hilarity, what with its continuing satirical value as an extreme example of the Korean variety of famous-for-being-famous, as well as its blunt, demanding manner and lighthearted insolence. To the frustrated demographic that has grown out of the pieties of childhood without ever quite coming to believe in the pieties (or enjoy the comforts) of adulthood, it acts as a kind of pressure valve, a spectacle of cathartic defiance of the qualities of Korean society English-speaking observers label, at this point reflexively, as “hierarchical” and “conformist.” The very qualities that have generated so much appreciation for Pengsoo in its adopted homeland may limit its appeal elsewhere, and thus hinder the fulfillment the oft-proclaimed goal of “world class” star status. But then, it’s not as if Pengsoo lacks the ambition: getting bigger than Pororo is a humble achievement compared to its more recently declared intention of getting bigger than BTS.

Related Korea Blog posts:

One of Korea’s Most Popular Cartoons Is About a Bus

The Secret Koreanness of Sticky Monster Lab, the Character Brand I Struggle to Resist

The Essential Korean Fashion Accessory of 2018: A London Review of Books Tote Bag

Travelogue Korea and the Dream of Isolation

Multicultural Love and Its Discontents

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.