Despite my long-standing interest in things Korean, I’ve gone in for very few of the “Korean wave” of cultural products that have reportedly swept the globe — or at least much of Asia and a bit of the West— over the past 15 years. Most of them never seemed targeted toward me in the first place: not K-pop, not K-dramas, and certainly not K-beauty products, though the mighty Korean cosmetics industry’s push to normalize of male makeup gains ground every day. The first Korean product I ever consciously consumed, apart from jars of kimchi and citron tea from Korean grocery stores, I got for free: Kakaotalk, the country’s free messaging and Voice over Internet Protocol app of choice.

Or maybe Silicon Valley would call Kakaotalk’s business model “freemium”: free to use for messages and calls, but with an ever-expanding set of extras to buy. The gateway drug is the “stickers,” whimsical icons featuring the Kakao Friends, a cast of anthropomorphic characters including a dog, another dog with a black suit and an orange afro, a cat in a bob wig, a radish in a rabbit suit, a duck with removable feet, and a genetically modified peach. Most casual Kakao Friends buyers no doubt make the transition to addiction at one of the Kakao Friends stores all around the country. Usually multi-story affairs occupying huge amounts of prime real estate, these sites of pilgrimage sell everything from Kakao Friends cellphone accessories to Kakao Friends dolls to Kakao Friends confections to Kakao Friends luggage. Many even have a Ryan Cafe inside, so named for one of the newer Kakao Friends, a lion without a mane.

Not to be outdone, Kakaotalk’s main competitor Line, operated by a Japanese subsidiary of Korean search-engine company Naver, has also created the Line Friends. This seemingly larger group includes a variety of comparatively normal animals, especially bears, as well as a few human beings and what looks like a ghost. Line has also set up character merchandise shops in not just Korea but Tokyo, Hong Kong, Bangkok, and New York. On the endless quest for synergy, it has also produced subsets of new characters with Japanese-designed global icon Hello Kitty and international K-pop boy band BTS. In recent years the “friends” business in Korea has taken on aspects of a gold rush: fewer and fewer categories of product, no matter how mundane, lack at least one brand that had tried to come up with friends of its own, and design students increasingly come up with not just concept products but concept friends to promote them.

I’ve never paid money for a Kakao Friends or Line Friends product, at least not one for me, but every time I see a new Sticky Monster Lab product I have to talk myself out of buying it. I now live in a household containing a variety of Sticky Monster water bottles and Sticky Monster soju bottles, a Sticky Monster lamp, a Sticky Monster clock, Sticky Monster wine glasses, Sticky Monster stickers, and the complete set of Sticky Monster stored-value transit cards. (Not that I need any of those last: in Korea, a developed country, debit and credit cards come with embedded chips compatible with bus and subway systems nationwide.) But that represents only a fraction of the Sticky Monster products produced and sold, usually in limited runs, since the brand’s launch by a collective of designers in 2007.

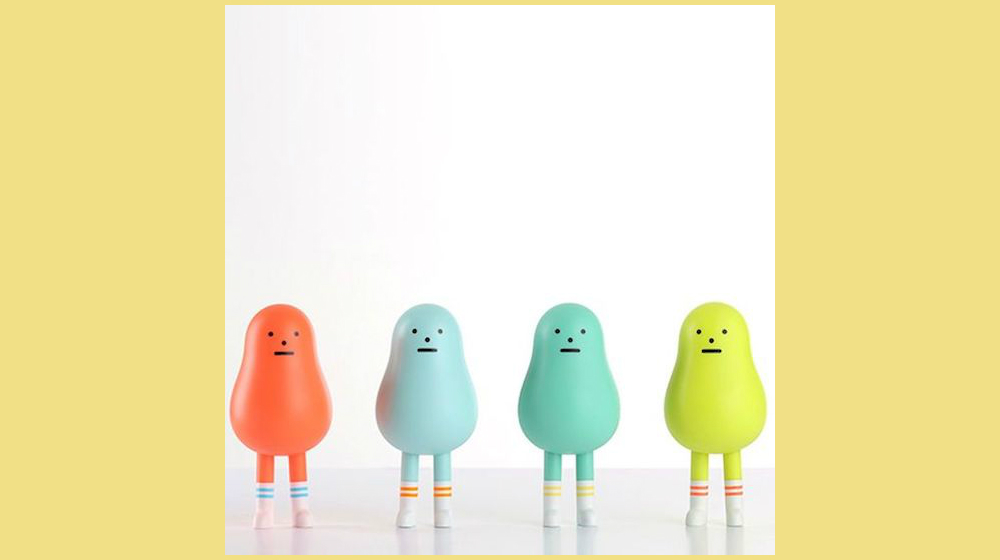

Sticky Monster Lab may not have the kind of retail emporia Kakao and Line do, but it’s a rare “cool” gift shop in Seoul from whose shelves not a single Sticky Monster stares out. “This is a Korean brand,” attendants often tell me when they see me looking at their store’s Sticky Monster Lab merchandise. I always make it clear that I already knew it was, thank you very much, but if you’d never seen a Sticky Monster before, you might easily have no idea. The bright colors and simple forms of its sometimes near-featureless characters — pear-shaped, spherical, sausage-esque — belong to no culture in particular. Some Sticky Monsters wear shirts or hats, but their only sartorial essential is a pair of white tube socks. On occasion their creators place them in unmistakably Korean settings, such as pouring one another drinks from a green-bottled beverage around a barrel-fire barbecue table, but for the most part the main cast of Sticky Monsters bear no marks of their national origin.

Sticky Monster Lab can appear to go out of its way not to make reference to Korea, either directly or indirectly. It unfailingly sets up one of the biggest booths at Seoul’s biannual Art Toy Culture expo (at which minor brands of “friends” and even “monsters” have multiplied, since nothing succeeds like success, especially here), often with artwork parodying Western, and only Western, movies and music: SML Wars instead of Star Wars, Sticky Monsters crossing Abbey Road, Sticky Bowie’s Monster Sane. Whenever I see this sort of thing, part of me always wants to ask Korean people if it’s weird, and part of me knows that they’d probably say that it isn’t. In interviews, the creators have framed the Sticky Monsters’ lack of identifiably Korean traits as a means of attaining universality — which, in Korea, too often means an approximation of the English language and Anglophone culture.

“SML is already attracting international attention with its peculiar wit and freshness,” says the brand’s website. “The monster character looks cute and simple at first sight but with a deeper look, it brilliantly reveals the dark side of reality. Surprisingly profound messages and emotional details hidden beneath its simplicity naturally leave the audience with strong impressions.” Against all odds, this got me thinking. For all the amusing design variations in Sticky Monster Lab’s products, it’s one particular and unvarying quality that wins me over every time: their blank faces. I wouldn’t have any interest in either a smiling Sticky Monster or a frowning one; those three dots above a straight line just make sense to me. They may also, deliberately or inadvertently, make the Sticky Monsters Korean after all.

A few years ago, Korean-American writer Wesley Yang made a splash with “Paper Tigers,” a New York magazine article on the extent to which Asian-Americans can deviate from the standard stereotypes. He begins with a consideration of his own face, with its expression that sometimes strikes him as “nearly reptilian in its impassivity.” Later in the piece he talks to J.T. “Asian Playboy” Tran, a Vietnamese-American who “travels the globe running ‘boot camps,’ mostly for Asian male students, in the art of attraction.” Yang watches him give a talk to a group of Yale undergraduates:

“One of the big things I see with Asian students is what I call the Asian poker face — the lack of range when it comes to facial expressions,” Tran says. “How many times has this happened to you?” he asks the crowd. “You’ll be out at a party with your white friends, and they will be like — ‘Dude, are you angry?’” Laughter fills the room. Part of it is psychological, he explains. He recalls one Korean-American student he was teaching. The student was a very dedicated schoolteacher who cared a lot about his students. But none of this was visible.

The condition is hardly limited to young men in America looking to hit the clubs. I’ve never taught here in Korea, but when I talk to Westerners who have, many mention the difficulty of getting used to their students’ constant mupyojeong (무표정), a kind of anti-expression that expresses nothing at all. These teachers might as well be lecturing to a roomful of Sticky Monsters, but where the mupyojeong makes their job difficult, it gives the Sticky Monsters their charm. (And as Scott McCloud argued in Understanding Comics, the more abstract a face, the more universal it becomes: “When you look at a photorealistic drawing of a face, you see it as the face of another. But when you enter the world of the cartoon, you see yourself.”)

Like Kakao Friends and Line Friends, Sticky Monster Lab has collaborated with other brands, but with a much wider range of them: its foreign partners have included MTV, Nike, Nissan Penguin Books, and even Playboy. It also puts on a regular event called SML Expo, usually in Taipei or Hong Kong. And like other businesses in this Korea’s export-built economy, it seems to operate on the theory that the path to success runs through as many countries other than Korea as possible. A fan might fear, and not without cause, that the effort to engineer appeal to a global audience — which official Korea periodically engages in to market the country itself — risks draining the product of its essence. But in an age when BTS, whatever their artistic merits, can top the Billboard charts while singing in Korean, maybe the Sticky Monsters won’t have to crack a smile any time soon.

Related content:

One of Korea’s Most Popular Cartoons Is About a Bus

Why K-Pop is the Same as Classic Rock

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.