Start asking Korean high-school students what career they want, and — assuming they’re giving the honest answers rather than the prestige answers — it won’t be long before someone says they want to be a comic artist. Or rather, they’ll probably say “webtoon” artist, that being the term of art for the form of comics now seen on screens all around the country. Unlike the horizontal newspaper comic strips I grew up reading in America, webtoons read vertically, from top to bottom, not for any reason to do with the now horizontally-written Korean language but for better scrolling on a cellphone. Though digital, the format also harks back, if inadvertently, to the progenitor of all modern Korean comics: Old Man Gobau (고바우 영감), whose four vertical panels appeared in national newspapers daily for 45 years, from not long after the Korean war until the final year of the 20th century, and whose creator Kim Seong-hwan died last month at the age of 86.

Only the rare teenager has thus actually read Kim’s strip, given that its long run — the longest of any comic strip in Korean history — ended the same year the oldest among them was born. But most of them will recognize Gobau himself, with his round spectacles and the single hair sprouting from his flat head. In one of the 14,139 daily strips in which he stars, Gobau explains that he began with three hairs but lost one during the Japanese occupation of Korea, and another during the Korean war. That Kim made it to the end of his life with much more hair than his signature creation was a stroke of luck, given all he’d experienced: born in Japanese-occupied northern Korea in 1932, he had the misfortune to be 17 years old at the outbreak of the war. It wasn’t long thereafter, in hiding from the North Korean troops sweeping every occupied Southern city for able-bodied young men to conscript, that he came up with the name Gobau, meaning a strong or stubborn rock, which he first adopted as a nom de plume.

“A high-school student and part-time magazine illustrator when North Korea invaded,” journalist Andrew Salmon writes of Kim in The Asia-Pacific Journal, “he recorded the dramatic events of those days in unique style: with that blend of delicate Oriental watercolors and the sensitive pen cartoons that would later become his trademark. After Seoul’s September 28th 1950 liberation, he was employed as a war artist by the Ministry of Defense, but it is his early sketches that capture what it was like to be a civilian on the peninsula in the midst of total war.” The sights Kim saw, drew, and painted included the smoke and flames of the fighting drawing ever nearer; hopelessly ill-equipped South Korean troops, North Korean tanks rolling through a fallen Seoul; his terrified and disconsolate countrymen; and plenty of dead bodies, both Southern and Northern. He then bore witness to the waves of joy and sorrow that accompanied South Korea’s transformation from an impoverished, shell-shocked half of a country into an industrial society that quickly joined the ranks of the world’s most highly developed nations.

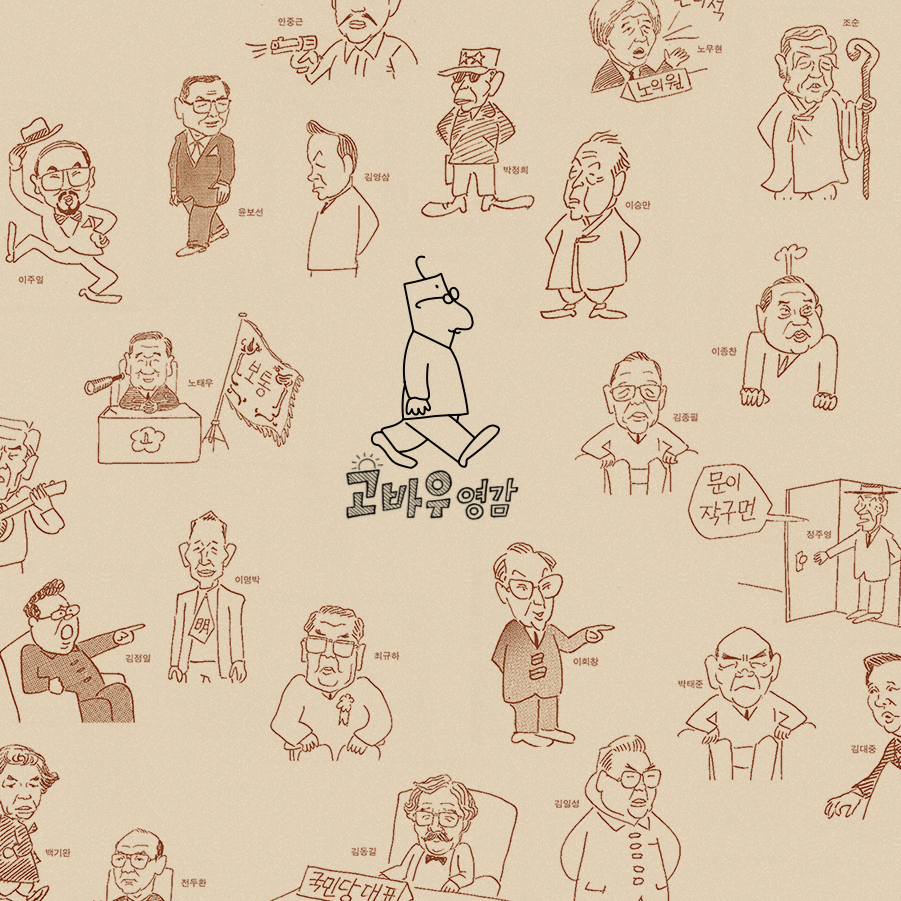

South Korea changed as much as Gobau didn’t. Though Kim began drawing the Old Man Gobau as a daily strip in 1955, had actually been using its protagonist in cartoons since 1950, making the span of Gobau’s appearance in newspapers exactly the same as the original run of Peanuts. Though Charles Schulz’s strip became a cultural institution (and has in recent years grown quite popular here in Korea under the title Snoopy) it was never the most artistically elaborate strip in the funny pages. But the stark simplicity of Old Man Gobau makes Peanuts look like Zippy the Pinhead, and over the decades Kim removed more from its artwork than he added. Whereas Schulz kept introducing new characters like Peppermint Patty, Franklin, and Snoopy’s cousin Spike to keep the strip fresh through every passing era of American culture, Kim required only Gobau himself, drawing his supporting cast from the ceaseless churn of real-life figures in South Korean public life — or indeed North Korean public life, since he didn’t hesitate to draw in the likes Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il.

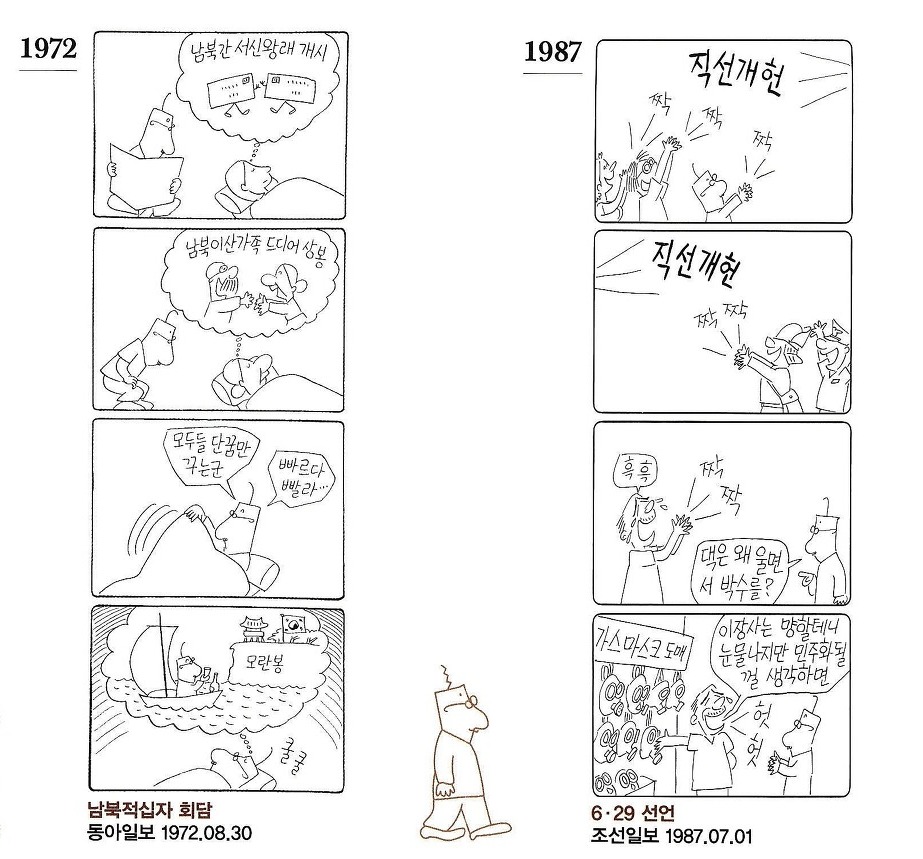

Though not, strictly speaking, a political cartoon, Old Man Gobau could hardly ignore political events: born into the still-new Republic of Korea, it ran through decades of military dictatorship followed by the democratization and opening-up of the late 1980s and early 1990s, and ended just after the near-debilitating setback of the Asian Financial Crisis. In 1972, days after the July 4th North-South Korea Joint Statement of 1972 that first signaled the possibility of reunification, Gobau looks into his countrymen’s sweet dreams of letters sent between and reunions with family on the other side of the border (above left). Fifteen years later, days after the June 29 Declaration of open presidential elections that put an end to the pro-democracy protests recently dramatized in the film 1987, Gobau asks a shop owner why he’s crying while applauding the announcement of constitutional reform (above right): gesturing toward his display of gas masks, an essential for demonstrators, the man explains that he’s thinking of the arrival of democracy as well as his store’s imminent failure.

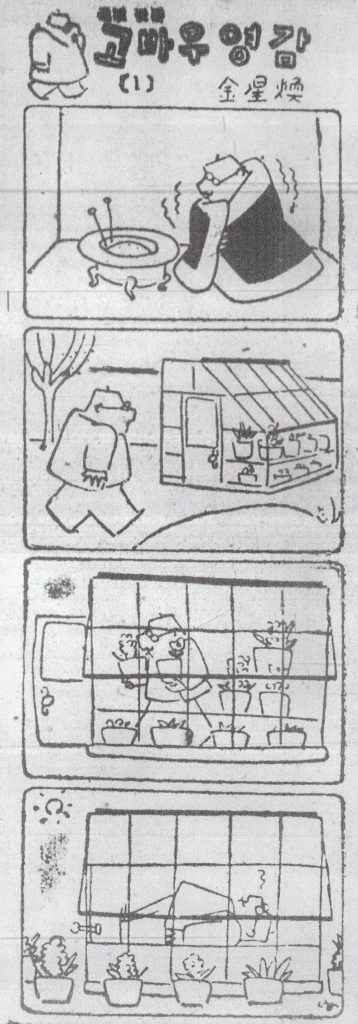

In stricter eras, Kim’s strips landed him in trouble every so often, resulting in censorship, fines, and even detention. Kim committed the best-known of these offenses to the state in 1958. The “Blue House Excrement-Bucket Incident” occurred after the publication of an Old Man Gobau (above) in which the title character sees a pair of janitors paying elaborate respects to a passing colleague also carrying buckets on his shoulders. When Gobau asks after the identity of the exalted man, one of the lowlier janitors replies that he carts excrement out of the Blue House, the South Korean presidential residence. The implicit portrayal of then-president Syngman Rhee as a kind of feudal lord may strike Westerners and even Koreans today as fairly soft satire, but at the time it cut deep enough to get the artist hauled in for four days of police interrogation.

Asked why he wanted to publish such a drawing, Kim responded that he wanted to become famous, and sure enough, the Blue House Excrement-Bucket Incident launched him into nationwide notoriety for the cost of a misdemeanor fine. As time went by Kim learned, as he later reflected upon in interviews, to lampoon society and politics in ways just metaphorical enough to keep the law from getting any traction on him. Thanks in part to that skill, he earned a large and loyal readership; no small percentage of the South Korean reading public old enough to have come of age with Old Man Gobau, and thus with South Korea itself, retains fond memories of opening the newspaper straight to Kim’s strip each and every day. And just as astute readers of the 20th century got all the political information they needed by reading Old Man Gobau, astute readers of the 21st can learn the history of South Korea by the same method.

In 2014 the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History mounted an exhibition called Our Modern History as Seen by Gobau, one of the many ways in which Kim’s creation has been embraced by the official Korea whose attention he once took pains to avoid. The previous year saw Gobau’s designation as South Korea’s Registered Cultural Property no. 538, and Korea Post marked his 50th anniversary in 2000 by issuing a stamp showing the character’s evolution over the past five decades. Gobau’s outfit may change, growing simpler with time as did the penstrokes of the strip itself, but his expression — or rather his mupyojeong, or “non-expression,” much like the face of a Sticky Monster — stays the same. The sole signal of Gobau’s feelings comes through the angle of his hair, an appropriately subtle indicator for such an equanimous character.

Kim also seems to have been possessed of a similarly unflappable personality, a nature paradoxically characteristic of his generation of Koreans: despite having gone through the late colonial period, the Korean War, and then the unprecedentedly accelerated development of literally everything around them, its surviving members come off as much more even-keeled than their more skittish and often despondent children and grandchildren. Though Kim chose not to pass Old Man Gobau along to a successor upon his retirement (as many high-profile American newspaper comic artists have done, with the notable exception of Charles Schulz), the strip’s legacy has lived on in other forms, not least in the name Gobau itself: taken as a symbol of the Korean people’s rock-like ability to endure, it appears in the name of all manner of businesses — bookstores, garages, restaurants — all over the country.

In a variety of romanizations, Gobau’s name has even made its mark outside Korea: take Kobawoo House in Los Angeles’ Koreatown, which the late food critic and Korean cuisine enthusiast Jonathan Gold named the essential restaurant for his favorite Korean dish, bossam, “a combination plate of steamed pork belly, raw oysters, special kimchi, raw garlic and a salty condiment made from tiny fermented shrimp, all of which you wrap into a sort of cabbage-leaf taco.” Next time you stop in for bossam, spare a thought for the single-haired old gentleman who weathered over fifty years of what, in his very last newspaper appearance, he called chunpung (春風, “spring wind”) and chuu (秋雨, “autumn rain”). Through half a century of turbulent times, Gobau and his creator showed a transforming South Korea to itself, each day giving its readers reason to smile — and just often enough, reason to laugh at all they’d been told not to.

Related Korea Blog posts:

One of Korea’s Most Popular Cartoons Is About a Bus

Reading Calvin and Hobbes in Korea

The Secret Koreanness of Sticky Monster Lab, the Character Brand I Struggle to Resist

Watching Korea Develop Through Sixty Years of Commercials

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.