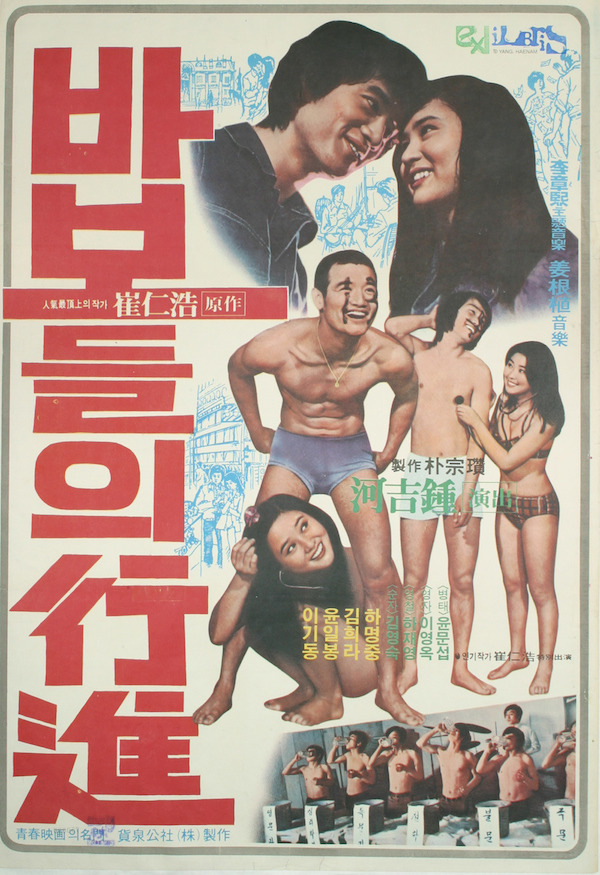

This is one in a series of essays on important pieces of Korean cinema freely available on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel. You can watch this month’s movie here and find links to previously featured movies below.

Mixers, sports matches, drinking contests, brushes with the law, anxiety about the future — Western audiences have come to expect all these elements from college comedies over the past half-century, and they’ll recognize them all in The March of Fools (바보들의 행진), a movie that belongs to essentially the same tradition. But it renders its college-comedy tropes a few shades darker to better reflect the reality of mid-1970s South Korea, a time and place caught between the demands of a very old social culture and the equally rigorous ones of the relatively new dictatorship intent on developing the country’s economy and keeping its people in line. Its hapless freshmen protagonists may get into as much trouble as the denizens of Delta House, but those guys never had to look into quite so deep an abyss.

At first glance, the Korean college life of the 1970s portrayed here seems to combine several conditions that never simultaneously obtained in America. Though The March of Fools‘ protagonists, a couple of casually philosophy-studying freshmen named Byeong-tae and Yeong-cheol, seem to lead pretty freewheeling lives, they also complain of having gone completely dateless up to the beginning of the story. “I’ve never chatted up a woman other than my mother,” says Yeong-cheol, in a line that at once underscores his misfit nature: he also tirelessly insists that his bicycle is a car and dreams, after retiring on the fortune to be made from selling miniature umbrellas to facilitate cigarette-smoking in the rain, of going out to sea to catch one particular, probably imagined, “beautiful whale.” But it also underscores the traditional, sometimes suffocating closeness of family relationships, especially with mothers, that can give rise to complications down the line.

Potential relief from their lifelong dry spells appears to Byeong-tae and Yeong-cheol in the form of a large-scale double date (an activity known, then as now, by the Konglish term 미팅, miting) between the men of their philosophy department and the much-coveted women of Ewha Womans University’s French literature department. After managing to scrape together the small entry fee, the two friends thrill to the prospect that “we could meet our future wives” on this, their very first date. But on the day of the event, after they’ve put on their finest suits — or rather their only suits, and ones a little stylistically outdated at that — they run afoul of an officer from the “hair squad,” one of the policemen then charged with dragging just such shaggy college boys as our heroes back to the station for sensible haircuts.

The ensuing chase counts, by the standards of Korean comedies of the day, as virtuosic: not only does it show off a few of the dizzying camera angles that director Ha Gil-chong and cinematographer Jung Sung-il use occasionally and to startling effect throughout the film, it encapsulates some of the complications of life in a fast-developing Korea. Though both Byeong-tae and Yeong-cheol study the kind of high-minded material that would have been the intellectual domain of respected aristocrats a century before, and one of them got the opportunity to do it because of the sheer wealth of his family, both of them feel like irredeemable losers. But even they, as they cross an overhead pedestrian bridge (that piece of infrastructure once so zealously embraced by industrializing east Asian metropolises), they stop to hand some change to an old beggar woman, a common sight in Seoul then but less so today.

Moments later, Byeong-tae and Yeong-cheol find themselves cornered on the very same bridge by the cops empowered to change their very hairstyles. Still, they prove sneaky enough to make it to the mixer eventually, and with their slightly rebellious manes intact at that. There they get matched, respectively, with a grade-grubbing gold-digger named Yeong-ja and the snippy, bespectacled Yeong-sook. Though neither seem like tremendous prospects, both quickly get the boys, starved so long of contact with womankind, talking of marriage. In addition to her objections to Byeong-tae’s earning prospects as a philosophy major, Yeong-ja also complains that their lack of an age difference would leave her an “old maid” by the time he returns from his mandatory three years of military service: “Mother says a girl should be sold when her price is at its peak.”

Such an appeal might seem to signal a certain traditionalism, but at other times Yeong-ja and her friends bemoan their role in 20th-century Korea: “A woman’s lot is pathetic in this time and age. You get married, have babies, life off a man, wait on your in-laws…” This sort of talk tends to come out in The March of Fools‘ several drinking scenes, most of which involve the quaffing mug after enormous mug of beer. Yeong-cheol gets especially deep in the comically oversized cups when after he begs Yeong-sook to meet him again and she walks out on him, claiming only to be stepping out for a phone call. “You’ll break the curfew if you don’t go now,” repeats the bartender as he struggles to dislodge the slumbering Yeong-cheol from his seat and close up shop. He leaves but doesn’t go right home, and as a result spends the night in a cell.

Such was the life of a spirited teenager, according to The March of Fools, in Park Chung-hee’s Korea. Prevented by law handed down by an authoritarian state playing the role of a strict parent to its unruly people from having a proper late night out, Byeong-tae, Yeong-cheol, Soon-ja, Yeong-ja and their like drink instead as a way of both distracting themselves from and allowing themselves to air their grievances with the society constricting them, and even the troublemaking that results runs mild. A “streaking” session, conducted without disrobing, prompts an objection from one of its participants: “It’s not streaking if we have our clothes on!” And so another labels it “streaking Korean style.” During one of their afternoons spent on a campus hillside, Byeong-tae puts a bold proposition to Yeong-ja: “Shall we kiss?” She replies with theatrical offense — “How dare you talk like that!” — and a self-defense-class attack to the groin.

And yet our heroes retain an idealism. “I have a dream,” Byeong-tae announces, in a quieter moment, to Yeong-ja. “What dream,” she asks, “a seagull’s dream?” We hear the line at least three times over the course a film, each one a reference to the title of the Korean translation of Jonathan Livingston Seagull, Richard Bach’s 1970 novella about a self-actualizing bird, which remains a steady seller here. When Yeong-cheol insists on the trustworthiness of his fellow man, it draws only scoffing from his friends. They test his belief by buying a newspaper from a pool-hall paperboy with a then-large-denomination coin, telling him to go get change and come back when he can. An hour later, when everyone but Yeong-cheol has lost hope, the paperboy finally returns, winded, with their money — his delay, he apologetically explains, the fault of a policeman’s extended reprimand for jaywalking.

The movie doesn’t get much more explicit in its portrayal of the conflict between humanity and authority than that, as indeed it couldn’t have, laboring as it did under the close eye of the censor back then. Before its original release 42 years ago, officials demanded the cutting of about half an hour of material they seem to have judged as portraying Korea too negatively, and the student protests, known to happen in the 1970s but which grew into a democracy-bringing phenomenon in the 1980s, manifest only as the suggestion of a suggestion. A more complete cut (the one viewable on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel) emerged in 1980, the year after Park died — but also the year after Ha died, having succumbed to a stroke at the young age of 37.

Though Ha, who famously studied alongside Francis Ford Coppola at UCLA, made seven other features in his short career (including two sequels to this film), The March of Fools remains by far his most memorable, and of all its sequences, none have found as permanent a place in the Korean cinematic memory as the buzz-cut Byeong-tae’s final departure for the army as a repentant Yeong-ja runs desperately up to his window on the train. “Have you eaten?” she asks, handing him a packed lunch. “Quit drinking and don’t skip your meals,” she importunes, running alongside as the train starts moving. “Always brush your teeth and wash your face. Got it?” A happy ending, in its way, for it reveals, with Yeong-ja’s words, that the relationship between she and Byeong-tae has finally achieved its ideal Korean state: that of diligent mother and dutiful son.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Seopyeonje: How a Surprise Art-House Megahit Showed Korea Its Own Forgotten Culture

Wangsimni, My Hometown: a Gangster (and a Filmmaker’s) Pledge of Devotion to Korea

Watching Madame Freedom, the Movie that Scandalized Postwar Korea

The Unbearable Preposterousness of Westernization: Park Kwang-su’s Chil-su and Man-su

Between Boring Heaven and Exciting Hell: Kim Soo-yong’s Night Journey

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.