Japanese names like Katomatsu Toshiki, Ohnuki Taeko, Yamashita Tatsuro, or Takeuchi Mariya may or may not mean anything to you. Rest assured, however, that there are Korean record collectors to whom they mean a great deal indeed. I see more than a few of them in person whenever Gimbab Records, a shop not far from where I live in western Seoul, puts on one of their sales of Japanese “city pop” records. These hotly anticipated events have usually involved an especially well-stocked collector parking a van on the store’s narrow street — almost an alley, really — and dealing the sacred pieces of vinyl straight out of the back. The sacredness comes through in the prices they pay, which surely exceed even what they cost new back at the height of Japan’s economic bubble in the 1980s. I’ve never brought along the kind of cash I would need to buy even half of what I might want, and deliberately so.

Like most city pop fans around the world, I just listen to the stuff on YouTube — and in fact discovered it on YouTube in the first place. If you’ve never heard city pop for yourself, you’ll better understand it not through a description of its sound but through a Youtube trip of your own. A YouTuber who calls himself Stevem has put together a video essay, “What Is Plastic Love?,” that explains just how a Japanese pop single from 1984, obscure even in its own country, racked up millions of views seemingly overnight after someone made it available in streaming-video form. That song, Takeuchi Mariya’s “Plastic Love,” has for the better part of a decade acted as the most effective gateway drug for the potential city pop enthusiast. All that time, the digitization and uploading of this “strain of lite, easy-listening J-pop that drew on a variety of American and Asian influences including funk, soul, disco, lounge, and even yacht rock,” as Rob Arcand and Sam Goldner put it in their Vice guide, has continued apace.

City pop’s 21st-century fan base knows no nationality, and its members have mixed, matched, and even remixed its-ever growing selection of acknowledged tracks into a great many themed streaming mixes, often visually accompanied by clips of vintage Japanese television and animation. For my money, the Chicago-based Van Paugam (whose work includes a brief history of city pop) has long made the best city pop mixes on YouTube, but earlier this year the Japanese recording industry — an aggressive entity, even by recording-industry standards — had his channel taken down, forcing him to start over again. You can still hear all of his mixes on Mixcloud, though, and not every city pop-minded YouTuber has suffered the same fate. Some have avoided it by diversifying their musical selections, even to the point of looking, or rather listening, outside Japan entirely: take, for instance, the recent appearance of city pop mixes from Korea.

Can we really speak of such a thing as Korean city pop? Whenever I go visit Japan, I go to the nearest Tower Records (which, yes, remains a going concern in Japan, due possibly to the aforementioned recording-industry aggression) and make a beeline for its city pop section, which is not only a demarcated part of the store but usually one that has its own listening station as well as detailed guidebooks for sale. Japanese record labels reissue the city pop classics of the 1980s at premium prices, and younger artists have also begun to revive and even intensify the styles the enormously wealthy Japan of that period: take, for instance, the thirtysomething duo Bed In, profiled in the New York Times last year as a shoulder-padded, miniskirted tribute to “the last gasp of the 1980s, a time of Champagne, garish colors and bubbly disco dance-floor anthems, and the last time many people in Japan felt rich and ascendant.”

Korea, too, was ascendant in the 1980s, though hardly in the same vertiginously glamorous manner. The ladies of Bed In may wear blazers “emblazoned with images of the Tokyo nightscape,” but few Koreans, no matter how nostalgic, would go out bedecked with the look of Seoul in the 80s, the gray, rough-edged, and rapidly expanding capital of a still-industrializing country, its citizens under a midnight curfew and its streets often clouded with tear gas from the latest clash between protesters and police. Seoul’s hosting of the 1988 Summer Olympics did much to usher in a celebratory mood, but in those days even sympathetic Western observers tended to regard Korea as little more than a lackluster Japan — as did a fair few Koreans, who looked with envy to the trends current in that both envied and resented country just across the East Sea (not, of course, the Sea of Japan).

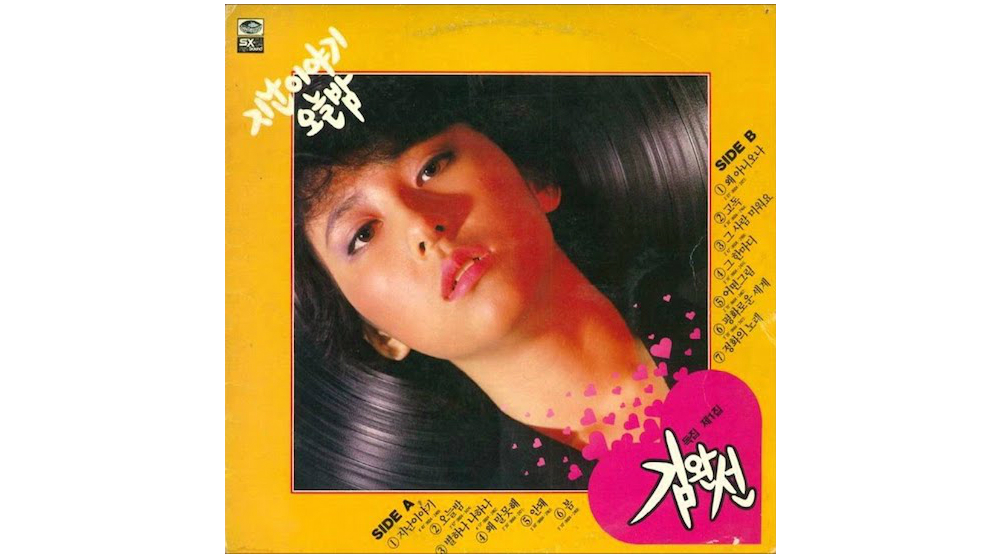

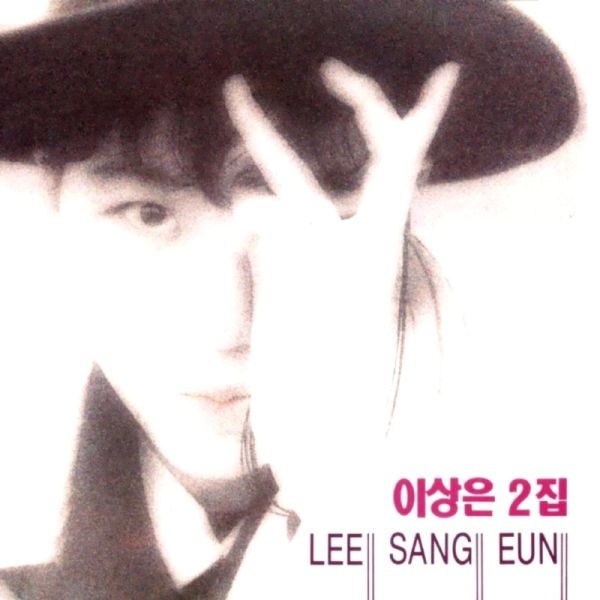

Korea’s makers of pop music, though hampered by a heavy-handed government that regarded culture as a means of enforcing its own ideas of public morality, certainly weren’t exempt from that tendency. Korean city pop sounds like Japanese city pop in the same way that Japanese city pop sounds like its own Western inspirations: similar, and even on some levels derivative, but also at just enough of an aesthetic and even technical remove to keep it interesting to foreign ears, including those that persist in rejecting (or at least refusing to re-evaluate) the funk, soul, disco, lounge, and yacht rock of the West. What’s more, the images of pre-1990s Korean pop singers stopped short of the heartthrob and sexpot, sometimes well short, and their awkwardness (usually mild, thought it occasionally reached masterful levels of its own) now offers a refreshing contrast to the many slickly featureless, unconvincingly eroticized young K-pop stars today.

The appeal of Korean city pop extends not just to curious foreigners but has come back around to Koreans themselves. Take, for instance, the YouTuber called HomeAloneBoy (Home Alone being a strangely beloved American film here in Korea, but that’s the subject for another post) who, over the past six months or so has put out four mixes that I recommend without hesitation as the place to start with Korean city pop: “Chill Summer Breeze,” “Warm on a Cold Day,” “Cigarette Smoke with Cold Breath,” and “Campus Couple.” (A few others have also put up mixes of their own as well; just search “Korean city pop.”) Their playlists show a range a bit wider than those of Japanese city pop mixes, which tend to stay strict about period and language: HomeAloneBoy includes, to name one telling example, a still-brand-new cover of Kubota Toshinobu’s 1996 “La La Love Song“ by Baek Yerin, a K-pop system-approved singer born in 1997. Last year, singer Kim Yubin of the girl group Wonder Girls even put out a city pop single with a B-side so brazenly similar to “Plastic Love” that its label was soon forced to withdraw it.

But most of the songs included come genuinely from the 80s, many of them by artists representative enough of that era that they’ve been used to evoke it in the last few years’ wave of film and television looking back at Korea’s once-shunned recent past. Memorable examples include Cho Yong-pil’s “Short Hair” (단발머리), which plays as the title character of the 1980-set A Taxi Driver crosses a bridge into a digitally de-skyscrapered Seoul, and Yoo Jae-ha’s sole album Because I Love You, which figures prominently into 1987, a movie about the decisive turning point in that decade’s student democracy protests. Even more of the music that falls broadly into the category of Korean city pop soundtracks the popular Reply (응답하라) dramas set in 1988, 1994, and 1997, or at least the first series and most of the second: the rest features whatever immediately succeeded Korean city pop before the rise of K-pop as the world now knows it.

The world now knows K-pop well, or at least better than it ever knew J-pop, even when Japan was at the zenith of its global soft power — a zenith that lagged some years behind the economic one. Today the Japanese economy enjoys it first fairly good times in decades, and Japanese popular culture looks back on the really good times thirty years ago. Korea wonders how much gas the “Miracle on the Han River” really put in the country’s tank, and popular culture here shows a greater willingness than ever to revisit the days when it was still in the midst of that unprecedented and in some respects brutal developmental process. Restaurants and bars have even begun to pay homage to those days: my favorite drinking spot in all of Seoul (which happens to be in the same neighborhood as Gimbab Records), a basement that plays nothing but Korean pop music of the 70s and 80s and decorates with nothing but artifacts of a similar vintage, convinced me the very first time I visited that I could have a life in Korea. And as for Korean music that pokes gentle fun, à la Bed In, at the heyday of tackily high living in Seoul, that heyday was seven years ago, and the music was “Gangnam Style.”

Related Korea Blog posts:

Yoo Jae-ha’s K-Pop Masterpiece Because I Love You, 30 Years After His Untimely Death

Why K-Pop is the Same as Classic Rock

Korean Punk and Indie Rock in a K-Pop World

Korean Cinema Looks Back at 1987, When Students Died and Democracy Was Born

As Detroit Shows Americans an American Riot, A Taxi Driver Shows Koreans a Korean Massacre

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.