After years of solo study, I first started taking Korean language classes at Los Angeles’ Korean Cultural Center. While sampling the levels on offer to find one that matched my ability, I noticed a trend. The classes started out huge at the beginner level, thinned out at the intermediate level, and got quite small indeed at the advanced level. That, you’d expect, but the type of people enrolled also changed on the way up: the ranks of the beginner class heaved with students brought there by their love of Korean pop music, or “K-pop” (perhaps you’ve heard of it), while, by the advanced class, they’d almost all fallen away, leaving, for the most part, me and a bunch of Korean-Americans finally interested in communicating with their grandparents.

Global interest in K-pop rose alongside my own interest in Korea — a pure coincidence, I can assure you, unless you buy this business about the pan-pop-cultural “Korean wave” supposedly crashing against shore after shore over the past decade or two. But there’s no arguing with all those Big Bang, Super Junior, Girls’ Generation, and 2NE1 enthusiasts packing the Beginner A classrooms: more so than the movies or the television dramas, the country’s disproportionately huge number of subtly different idol singers, girl groups, and boy bands have, for better or for worse, defined for the world what the world has begun to call “Korean cool.”

“Japanese cool is quirky, the sum of the nation’s eccentricities,” writes Jeff Yang at CNN. “Hong Kong cool is frenetic, representative of the society’s freewheeling striving spirit. American cool is casual: It’s cool that’s anchored in doing without trying, it’s about being quintessentially effortless. By contrast, Korean cool could not be more effort-ful,” with its “candy-colored, otherworldly aesthetic,” its performers “invariably dancing in perfect sync,” having been “recruited as adolescents and trained for years in groups that are required to live, take classes, eat, sleep and rehearse together until they’ve achieved a transcendent level of harmony.”

Growing up in America, I had plenty of time to grow weary of American cool, with its unceasing pressure to go your own iconoclastic way — as long as you do so as visibly as possible, and in such a way as to make it seem as if you not only don’t notice the eyes on you, but that you didn’t want to turn them toward you in the first place. The defining memory of the cultural landscape of my adolescence: “alternative rock” wasn’t just a commercial radio format, it was the most popular commercial radio format. There, as in many areas of mainstream culture, the substance didn’t quite match the image.

My last memorable disappointment with this sort of thing came the first time I heard the actual music of Lady Gaga. Had the compositions of her songs sounded half as bold as the her outfits looked, we’d have had a revolution in pop, but as it stands, her outlandish appearance only casts into relief the blandest elements of her only faintly-adventurous-by-mainstream-standards hits. By the same token, if the compositional wing of the K-pop industry spent half as much energy pushing their music into new territories (rather than tweaking and refining whatever the last big group did) as the video and stage-show producers do with those candy colors and perfect synchronicity, I’d have started studying Korean out of a love of K-pop myself.

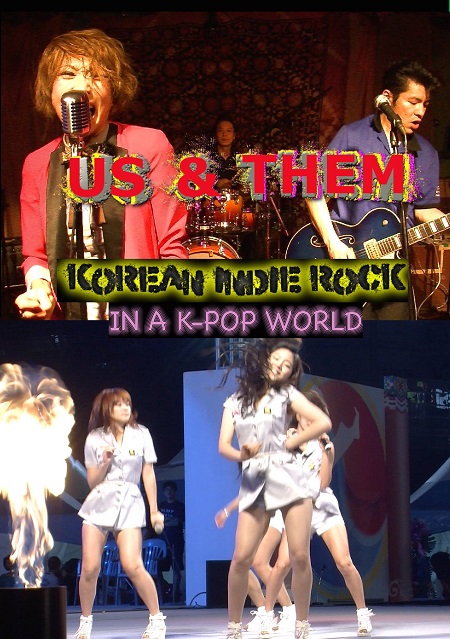

“K-pop looks good,” says Bernie Cho, the Korean-American president of Korean music distribution and marketing agency DFSB Kollective. “Some would say it sounds good,” he adds, making the biggest laugh line of Us and Them: Korean Indie Rock in a K-Pop World, a new documentary by academics Stephen Epstein and Tim Tangherlini. It follows up on Our Nation: A Korean Punk Documentary, which they put out in 2002. I caught a screening last week of both films, back to back, at Seoul’s Club Ruailrock (롸일락), followed by live sets from a few of the bands featured therein — some closer to punk, some closer to rockabilly, some other brands of rock entirely, all of them united in the cause of not being K-pop.

Taken together, the documentaries constitute a fascinating portrait of not just the evolution of Korean punk and indie rock, which has had to develop on the thin margins of Korean life, but of Korean life itself. One friend remarked that the screaming girls at the foot of the stage in the early 2000s seen in Our Nation looked, even just by comparison to the screaming girls at the foot of the stage in the early 2010s seen in Us and Them, almost North Korean — that is to say, they looked less affected by the sort of cosmetic surgery-crafted standard look that, in the years between the two movies, has influenced the image of everyday South Koreans and positively defined the image of the South Korean pop star.

That counts as only one of the many things a young Korean rocker might have to rebel against. As I grew up and watched some of my friends get into punk, I have to admit I wondered what they saw in it, or rather heard in it; as a score, it might well have suited the crumbling New York or London of the 1970s, but the suburbs of Seattle in the 1990s? (Not that the theatrical booze- and pill-fueled angst of that era’s “alternative” rock struck me as relatable either.) But now I wonder how any Korean high-school student, subject to the all-consuming morning-noon-and-night pressure of Korean social and academic expectations, could do without the catharsis punk provides.

When Westerners imagine East Asian interpretations of Western music, they often imagine a sort of rigidly imitative formalism, the kind out of which Dave Barry got a few miles when he went to Tokyo and observed the street rockers and dancers of Harajuku, a scene that, he writes, “served as heartwarming proof that rock music is indeed the universal language of the young, and the Japanese young cannot speak it worth squat.” He perceives “a Hipness Gap, a gap between us so vast that their cutting-edge young rockin’ rebels look like silly posturing out-of-it weenies even to a middle-aged dweeb like myself. They buy our music, they listen to our music, they play our music, but they don’t get our music.”

But Dave Barry Does Japan came out in 1992, and this is the 21st century; we’ve long since transcended ideas of “getting it” and “not getting it,” right? Don’t we we now have a zeitgeist that renders Japanese reinterpretations of vintage Americana a worthier object of fascination than the genuine articles? And besides, this is Korea, a culture characterized less (in the view of its own people) by constant self-possession than spontaneous emotional outburst, and less by the disciplined replication of things foreign than by their indiscriminate mixture. This sensibility gave the first wave of Korean indie rock, reflected upon in Our Nation, its particular appeal.

Epstein, in an article on both documentaries for The Asia-Pacific Journal, writes about 1989, his first year in Korea, a time when, “long before the term K-Pop was coined, Korean popular music was rife with anodyne but often overwrought concoctions and Western soft rock was ubiquitous,” a mixture he experienced as “a mild form of aural torture.” But when he returned in 1997, things had changed. “How did punk rock get to Korea when eight years ago I couldn’t even imagine that there would be anything like this?” he asked himself. And as for the new sounds themselves, “Imagine listening to pop music for your whole life, and then suddenly over the course of a year, somebody introduces you to Nirvana, the Sex Pistols, Green Day, Led Zeppelin, all at once. What kind of music are you going to make?”

That question lies at the heart of Our Nation and Us and Them‘s project, as it will presumably lie at the heart of whatever documentary on Korean punk and indie rock Epstein and Tangherlini make next. They chart a kind of internationalization of the music: first, Koreans adapted the threads of Western rock for their own expressive purposes (an early compilation carried the title Joseon Punk (조선펑크); a later band branded themselves as playing “kimchibilly”); then, as the foreign population of Korea grew, the Westerners themselves joined in, forming mixed-nationality bands with the Koreans; now, Korean bands have begun to play in the West, and Western bands come to play in Korea — the sort of ongoing transoceanic musical exchange that must warm the heart of any cultural globalist.

But will there come a point, I wonder, when we stop calling it Korean music? For all their close scrutiny and impeccable assumption, even improvement, of the form of the postwar American greaser, those Harajuku kids Barry ridiculed, “all dressed identically in tight black T-shirts, tight black pants, black socks, and pointy black shoes,” each one with a “lovingly constructed, carefully maintained, major-league caliber 1950s-style duck’s-ass haircut,” come off no less Japanese — and, in a way, more Japanese — for it. He witnessed a mastery of varying surfaces, even foreign surfaces, but a mastery itself rooted in a deeper place. In the words of Pico Iyer, “Japan is ready to change its clothes so often in part because it changes its soul so rarely.”

How often does Korea change its soul? An ultimately unanswerable question, but one that any watcher of Korean popular culture can’t avoid. Our Nation and Us and Them reveal a subculture more porous, more subject to permanent influence, than any of my acquaintance in Japan, and perhaps, so far, a more fruitful one for it. I get the sense of K-pop, which by nature seeks an ever bigger market, moving toward a kind of linguistic dilution and geographical nowhere-ness that might one day, for all the soft-power value of the brand at the moment, let it cast off what Epstein calls its “Special K” and become a kind of (alas, even blander) global pop music. Will Korea’s punk and indie rockers, in their oppositional manner, show the way down a more interesting path of musical internationalization?

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.