This is the third of a three-part series of essays on Korean crime fiction. The first part, on Jeong You-jeong’s The Good Son and Kim Un-su’s The Plotters, is here, and the second, on Kim Young-ha’s Diary of a Murderer and Seo Mi-ae’s The Only Child, is here.

Watching a lecture from Sebashi, the Korean equivalent of TED Talks, I heard the speaker mention a previous speaking engagement he’d had in an unusual venue: a women’s prison. Most all of the inmates, he said, had been locked up for financial malfeasance of one kind or another. This mildly surprised me, despite the well-documented lack of propensity on the part of womankind toward more violent varieties of crime. Then I considered the disproportionately numerous stories of financial ruin that I’ve heard in Korea. In the United States, one can still only get so many degrees of separation away from lingering effects of the Great Financial Crisis (to say nothing of coronavirus-related economic hardship), but here it seems that everyone knows at least a few people who’ve lost everything in a failed business, got swindled in a bad deal, or emigrated in flight from crushing debt.

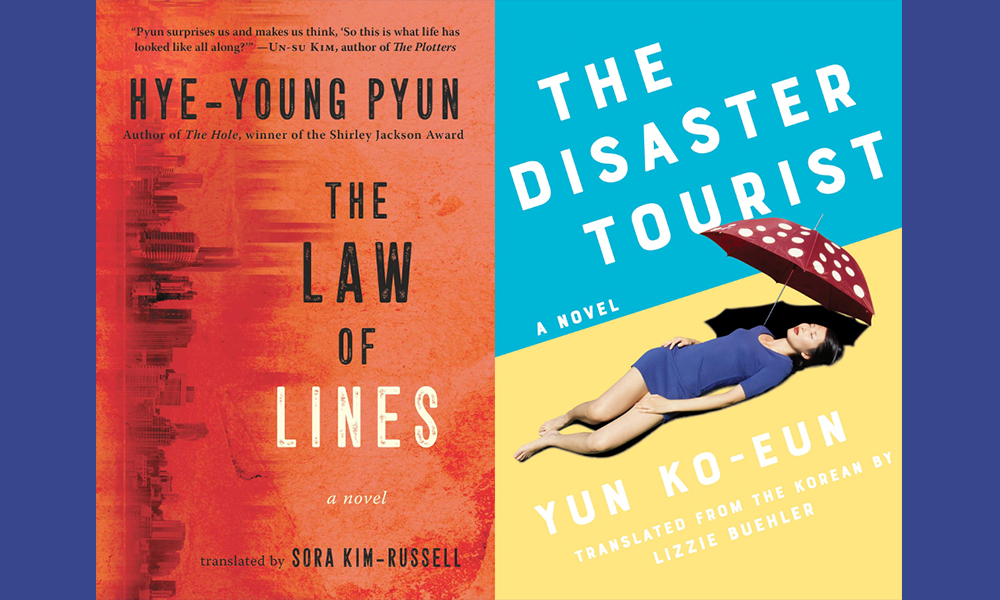

Given that, it seems implausible that the first four Korean crime novels I’ve covered in this series — Jeong You-jeong’s The Good Son, Kim Un-su’s The Plotters, Kim Young-ha’s Diary of a Murderer and Seo Mi-ae’s The Only Child — have so little do do with money. This contrasts with American crime fiction (or at least what I’ve read of it), many if not most of whose plots are set in motion by the desire to ill-get some gains. In this sense Pyun Hye-young’s The Law of Lines, translated by Sora Kim-Russell, and Yun Ko-eun’s The Disaster Tourist, translated by Lizzie Buehler, go the American way. Two of the most recent works of Korean crime fiction successful in English, they both tell stories intimately concerned with money and what people will do get it, but without the heists, drug deals, and gangland machinations familiar to Western readers.

Like The Only Child, The Law of Lines opens with a deadly house fire — or rather, an explosion — the accidental or deliberate ignition of which comes under investigation. It destroys the home and eventually kills the single father of a 27-year-old woman named Se-oh, who already had it bad enough: having struggled to extract herself from a multi-level marketing scam, she lives in fear of being recognized by one of the many acquaintances she attempted to recruit. Figuring that her dad set off the explosion on purpose, committing difficult-to-detect suicide as an escape from his own financial woes, she makes it her life’s mission to hunt down and murder the debt collector who had been badgering him day and night. But that debt collector, a fellow late-twenty-something soon to be priced out of the dank apartment he shares with his disabled mother, is hardly doing better himself.

Pyun constructs an intersection of Se-oh’s life with that of a woman named Ki-jeong. A schoolteacher who, in her late thirties, still lives with her mother, she counts by this novel’s pinched standard as the most successful major character. But she, too, incurs a great loss right at the outset, when a call from the police informs her that the body of her younger sister Ha-jeong has been dredged out of a river in a distant provincial town. The product of their father’s dalliance with another woman, Ha-jeong had come to live with Ki-jeong’s family at five years of age. But never was she granted full membership: when her mother — who “regarded herself as the child’s babysitter” — would give Ha-jeong her daily bath, the look on her face “had always been flat and harsh, less like she was bathing a young child than scrubbing a mud-caked, oversized radish.”

Understandably inclined to go her own way, Ha-jeong ended up in the acquaintance of Se-oh, or so Ki-jeong discovers when she looks into her Ha-jeong’s cellphone records. Curiosity about what her sister had to say this Se-oh before she died turns Ki-jeong into an amateur detective; Se-oh, for her part, launches an even more intensive one-woman investigation into the daily routines of Su-ho, the collection-agency employee who had been assigned to her father. Their individual searches lead them through a Seoul of dingy apartment complexes, cheap blood-sausage joints, and crowded subway trains, all of it far indeed from the images of nouveau-riche Gangnam even now projected around the world by Korean television dramas. When Ki-jeong and Se-oh finally meet, they do so in a room of a goshiwon, the spare and coffin-like accommodation rented by the month to students in particular and the destitute in general.

One connection between Ki-jeong and Se-oh takes the form of a young man named Bu-wi, who had been involved at different times with both Ha-jeong and Se-oh’s best friend Mi-yeon. But whatever his favor with the ladies, money problems alone have shaped his life. “His troubles had begun during the summer vacation of his third year in high school,” Pyun writes. “His father had expanded his business a couple of years earlier and overextended himself. The ensuing financial trouble was like a runaway train. Bu-wi knew there was no money for him to go to college, but he took the entrance exam anyway, and despaired to learn that he’d been accepted into the top medical school of his choice.” Hence the surprising ease with which a desperate Se-oh brought him into the multi-level marketing scam, just as Mi-yeon (herself already escaped and vanished into Seoul) had previously done to her.

Apart from the claims of violence and sex, crime fiction holds out to its readers the promise of professional knowledge. Usually the professions are related to the criminal or policing arts, but in these novels — which, incidentally, treat violence un-luridly and sex hardly at all — none of the protagonists specialize in either the breakage of the law or its enforcement. The Law of Lines‘ characters are more mundanely employed, when employed at all. Su-ho, the debt collector, did without work until a former army buddy recommended the David Credit Information Company. “His criteria for selecting a job had been simple,” Pyun writes. “It had to be a place where he could wear a suit and be at work by 9:00 a.m.,” given that “his father, a manual laborer who’d been dead a long time now, had always had to check the weather before heading out to work.”

Alas, even this degree of class mobility proves elusive. His office his team leader wears “a suit perfectly tailored to fit him in the shoulders. Compared to Su-ho’s suit, which grew shabbier by the day, his suit grew sharper by the day. Why was that? And why was Su-ho still unable to buy himself a single decent suit despite working so hard?” His daily dealings with dissembling, hostile debtors shed light on his own downtrodden condition. “The bad luck poverty ushered in was close to fate. That is, once you were under its evil spell, everything turned bad. Paying for surgery for a parent on the verge of death. Cosigning for an older brother who was starting a new business. Getting injured on the job when no one else in your family was bringing in any money. No matter how they started, the stories all ended the same way.”

Su-ho barely scrapes by at his job; Ki-jeong, at her school, performs somewhat better, though her impulsive striking of a kleptomaniac student brings her to the verge of termination. Being put on mandatory leave as a result provides her with the time to find the facts of her sister’s death, a process that eventually forces her into self-reflection. “She’d gotten a lot of things wrong,” Pyun writes, leading into a litany including everything from “using grades as a way to keep kids in line” to “scoring their work based on their attitudes or personalities, and thus grading them according to her own assumptions or prejudices rather than their individual efforts or achievements” to “not bothering to conceal from them how exhausted the work made her.” Whatever her failings of professional ethics, Ki-jeong’s narrative journey could well be read as one toward an understanding of basic personal decency.

The Disaster Tourist centers on another professional woman, albeit one employed in a much less conventional industry. The 33-year-old Yona works at Jungle, a travel company that organizes group tours to the world’s trouble spots. It is to the kind of people who carry “survival kits, generators and tents as they searched out disaster zones worthy of exploration” that Jungle directs its advertising: “Experience the Ashen Red Energy of a Volcano! Feel Mother Earth Tremble. Ride Noah’s Ark and Be the Judge of the Seas. Tsunamis: Calamity and Horror Before Your Eyes.” But after a decade at the company, Yona has come to understand that “adventures like these reinforced a fear of disasters and confirmed the fact that the tourist was, in fact, alive. Even though I came close to disaster, I escaped unscathed: those were the selfish words of solace you told yourself after returning home.”

Despite appearing to be a dedicated and reasonably successful disaster-tour designer, Yona has, like Ki-jeong, recently committed the kind of professional foul that necessitates time away from the office. Her superior orders her to go on an underperforming disaster tour herself and report back on whether or not Jungle should keep offering it. And so, not far into this short book, Yona finds herself at resort on Mui, an island off the Vietnamese coast whose disastrous attractions amount to no more than an unthreatening-looking volcano, a lake that used to be a sinkhole, and a nasty tribal massacre that occurred back in the 1960s. The first thrill of this underwhelming trip comes — for the reader, at least — on the train back to the airport, when Yona ends up in a section that detaches from the others and takes her to an even remoter corner of this remote place.

In this part of the world traveler’s English is apparently useless, as Yona discovers when she asks a member of the train staff for help. “The employee didn’t understand,” writes Yun. “Even so, she comprehended the situation and explained something energetically in the local language.” There follows a substantial direct quotation of her explanation — “Two stops ago, the car you were supposed to be on shifted on to different tracks. That train’s an express. You won’t reach your destination on this local track,” and so on — followed by a bit of omniscient narration declaring that “Yona couldn’t understand the words, but she managed to catch a few things from the woman’s gestures and the atmosphere.” Though brief, the episode reads in English as a disorienting break from the conventions of free indirect speech, which normally, when following Yona, would convey only what Yona herself knows or understands.

Such ambiguity of voice isn’t uncommon in Korean fiction, and at any rate it becomes more useful to Yun as the novel goes on. Drifting from one character’s consciousness to another — or to the consciousness of no one in particular — allows her to illuminate the pressures acting on the residents of Mui, as well as to comment on the dynamic between the island and the wider world. Sometimes this comes from a character’s mouth: “Since signing a contract with Jungle and building the resort,” one of them explains, “Mui has been tailoring everyday life to fit its role as a disaster zone. That’s led young workers who left for other regions to come back. Now, if disaster disappears from Mui, life disappears, too.” Hence the need to engineer a new disaster, an endeavor with which the stranded Yona gets involved, and into which she soon thereafter throws herself.

Yona collaborates not for the money, exactly, but to maintain her standing at the Jungle. The company provides for its staff’s every personal need: “It encouraged office couples, and it even provided opportunities each weekend for single employees to meet other singles. It also offered nearby employee housing. A doctor’s office, theatre, sports center, and shopping mall were all located inside the office.” But “the moment you quit your job, you had to restructure your entire life,” and part from her consistent if often thwarted efforts at Jungle, she has only the standard-issue daydream of one day opening a coffee shop. She is, in other words, the childless, unmarried, office-optimized Korean Everywoman of the 21st century, albeit one involved in an unusual line of work. (And even at Jungle, she still has to endure her boss’ groping in the elevator.)

The locals who take part in staging a new and distinguishing disaster for Mui, however, do it very much for the money. Hoping to set their families in good stead, some sign up for likely or certain death: one volunteers because, “like many others, he needed money more than he needed life.” But the best-laid schemes of Koreans and islanders gang aft agley, and any reader who takes Yun’s early mention of a giant trash island floating across the Pacific as an ill omen will be right to do so. The outcome is a commentary, not exactly subtle, on how now-developed countries like South Korea do as they destructively please with neighbors still belonging to what’s these days called the developing world. (At the same time, Yun illustrates, a vogue for Korean lettering has the Vietnamese applying it nonsensically to their vehicles in hopes of raising the resale price.)

Plans also fall apart in The Law of Lines, the subsistence lifestyles of whose characters suggest that South Korea never did make it out of the developing world. The real crime, a rudamentary reading might convince one to say, is capitalism; I think more of Venkatesh Rao’s concept of the “fourth word,” which emerges where “large numbers of people fall through the cracks of presumed-complete development and find themselves in worse-than-third-world conditions: more socially disconnected, more vulnerable to mental illness and drug addiction, with fewer economic opportunities due to the regulation of low-level commerce, and less able to stabilize a pattern of life.” The reception given to The Law of Lines — and to The Disaster Tourist, which won this year’s Dagger award for Crime Fiction in Translation from the U.K. Crime Writers’ Association — suggests, in the West, a certain familiarity with the root of the evil at hand.

Related Korea Blog posts:

The Korean Literary Crime Wave: Jeong You-jeong’s The Good Son and Kim Un-su’s The Plotters

The Korean Literary Crime Wave: Kim Young-ha’s Diary of a Murderer and Seo Mi-ae’s The Only Child

Let’s Get Out of Here: The Bitter Korean Neorealism of Yu Hyun-Mok’s Aimless Bullet

Six Expatriate Writers Give Six Views of Seoul in a New Short-Fiction Anthology, A City of Han

An American in Taiwan — with a Korean Tour Group

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.