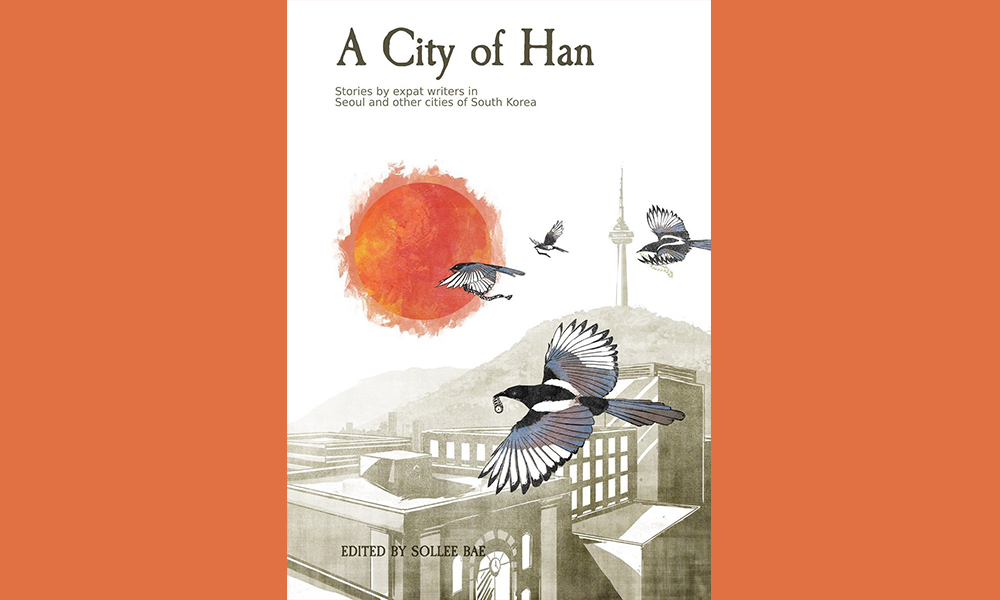

As a cradle of expatriate literature, Seoul has thus far proven to be no Prague, Mexico City, or Tangier, to say nothing of a Vienna or Paris. That’s not for lack of desire among expatriates themselves: every few months here I get word of the existence of another Westerner-oriented writing workshop, or contacted by another reporter or teacher certain he’s got a novel in him. But many such expatriates, yet to find their way out of self-published obscurity, will admit that this city is something of a faulty launchpad for a literary career, at least for those writing in languages other than Korean. In English, attempts are nevertheless made from time to time to harness the writerly energies of the expat population, the latest of which takes the form of a six-story anthology called A City of Han, compiled by Seoul native Sollee Bae.

In her introduction, Bae writes of asking others for explanations of her hometown’s failure to gain literary traction. “Their answers were surprisingly unanimous,” she reports. “Seoul did not have a defining character. It was too bland. It was the quintessence of a modern metropolis, made up of concrete buildings and wide roads and a grey sky. If we were to compare it to a person, it would be that man or woman who worked for a marketing firm, dressed sensibly, and carried the last year’s model of iPhone (but no older).” That’s not an entirely unconvincing explanation. For my part, I’ve long wondered if the city simply looms too large to clearly be seen. Unlike the capitals of the US and Europe, whose size and power haven’t persuaded the countries that produced them to consider them exemplary rather than exceptional, Seoul — in the eyes of all but nature poets and travel writers — is South Korea.

The difficulty of rendering Seoul with a distinct identity, not unexpected among a class of residents who often struggle to understand the signs in its storefronts, afflicts Korean writers as well. I once stumped a well-known novelist here by asking for recommendations of novels with rich visions of the city, and he’d written an internationally acclaimed one himself. Korean authors telling stories with Korean characters can’t easily avoid writing about Seoul, but expatriates can — and in various forms, do — tell stories of Seoul practically without involving Korean characters at all. This owes to the intersection of the “write what you know” principle and the insular lifestyles of a certain kind of Westerner in this country: those who fashion for themselves an approximation of the life they’d have lived back in their homeland, associating exclusively with Westerners and the kind of English-speaking Koreans who take pains to set themselves apart from their countrymen.

Such a lifestyle is central to Matthew Grolemund’s “Playing the Blues in Seoul,” a story narrated by an English teacher from Tennessee out on the town with a friend who’s about to move back to England. “Jimmy’s last night is a special occasion, so I agree to meet him and a few of our old hagwon co-workers at Magpie for beer and pizza around six,” he says. “By the time we head to Phillies at seven-thirty, I can’t tell if I’m buzzed or stuffed or a combination of both.” A hagwon is a privately owned academy usually attended by students after their regular school day; the many hagwon that sell English classes employ large numbers of Westerners for low-intensity teaching, though the hours can be long and the conditions wearying. (In No Couches in Korea, Kevin M. Maher’s recounts the life of a hagwon teacher in greater detail.) Magpies and Phillies are both real, popular pubs in Haebangchon, a part of the greater Itaewon area frequented by English teachers and other foreigners (and recently featured here on the Korea Blog when it experienced an outbreak of the coronavirus).

Grolemund’s narrator plays the guitar, and his best Korean friend Ho-joon plays the harmonica. He recalls the occasion of their first meeting, at night on the Seoul subway, when Ho-joon — standing out with “his buzzed hair, torn jeans and Janis Joplin T-shirt,” and more so by being being “the only person on the train not staring at his phone” — strikes up a conversation in English. The two other Koreans in his circle are women, his bandmate Song-eun and girlfriend Eun-song. Both are English-speakers, though of different status: “My girlfriend, who learned English from academies and Western culture from episodes of Friends, is a bit jealous and distrustful of my bandmate, who learned both those things by spending nearly half her life in the United States.” This speaks to the protagonist’s social insularity, but it also offers an insight into the way proficiency in the English language and connections to the West are used here as a means of jockeying for position, an especially grinding quality of Korean life even for Westerners outside the hagwon industry.

A chance English encounter between Korean and foreigner on a moving train also sets off Ron Bandun’s “Kyungsung Loop,” though the foreigner is Japanese and the time is the early 1930s, the era of Korea’s occupation by Japan. The narrator, a civil engineer named Nishimura Hidemitsu, thus refers to points in and around the city of “Keijo” by colonial names — Honmachi, Seishomon, Akenri — that even Seoul-savvy readers won’t immediately recognize. (“Ron Bandun,” I suspect, is the pseudonym of a Seoul-resident Westerner known for his familiarity with the urban ruins produced by the city’s unceasing cycle of development and redevelopment.) At first Nishimura takes a supercilious interest in Hwang-bo, the young Korean he sees riding the titular line every day with a Bible in his lap. Hwang-bo expresses an eagerness to learn Japanese and study at Tokyo Imperial University, and each time Nishimura encounters him over the subsequent decade, providing help when he feels like it, Hwang-bo appears to have taken another step toward assimilation and prosperity.

Nishimura eventually returns to Japan, but decides to bring his new family to Korea (or rather, “Chosun”) when the Second World War seems nearly lost. There he spots a Hwang-bo reduced to manual labor, digging up the rails of decommissioned train lines. Not long after the arrival of the Americans in September of 1945 (“to a dismayingly enthusiastic welcome from the locals”), Nishimura’s home is expropriated. With his wife, daughters, and a single trunk of possessions he makes for what he knows as Ryuzan Station, where a train can take them to a Japan-bound ferry. Amid the chaos there he encounters Hwang-bo once more, now employed as a station master. Hwang-bo does Nishimura the final favor of giving him a set of tickets, but not before flatly informing him that “this is Yongsan Station.” And it is in modern Yongsan that the next story, “Mosquito Hunters of Korea,” opens: “The only remarkable feature of the Yongsan bus terminal,” writes its author Ted Snyder, “was just how American it looked.”

A former United States Army entomology officer who spent time stationed in Korea, Snyder might well have been expected to write a story not just about American military men but set in the part of Seoul host, until recently, to Yongsan Garrison. But he hews still closer to what he knows in making all his characters specialists in the mosquitoes of Korea, specifically those that breed in the Demilitarized Zone along the North Korean border. What at first sounds like military-entomological shop talk in a tavern “down some forgotten side street” over “a bowl of milky-white makgeolli” gains an undercurrent as dark as that of the otherwise highly dissimilar “Umchina,” which opens A City of Han. In it author Eliot Olesen deals with a condition much more commonly lamented by foreigners than the diseases carried by the genus Anopheles: the evident pressure on young (and formerly young) Koreans to succeed, but even more so to keep the signs of success on constant display.

Unemployed in his mid-twenties and living with his widowed mother, Min has not attained success, but at least he has a decent ride. “Driving a car to Gangnam was ill-advised unless the car was expensive enough,” Olesen writes. “Min’s BMW was just passable as a high-end import. His mother had purchased it for him when he graduated from Cornell, which she regarded as just passable for an Ivy League.” She habitually compares him to the titular umchina, a Korean expression that contracts the words for “mom’s friend’s son”: “Jay the Samsung man had gone to Harvard. He had an MBA already.” Min, by contrast, sleeps in his car parked in a Gangnam back alley so as not to get mom too excited when he heads off in the morning to another hopeless conglomerate job interview. “He had the diploma, but lacked the grades. He had the pedigree, but lacked the connections. Most of all, he lacked the suave nature of a Hyundai man, a Samsung man, an LG man — they were all the same, and everyone wanted to be one.”

While those explanatory lines are hardly the story’s only violation of show-don’t-tell, nothing in it rings particularly false. In not driving her protagonist toward a final, despairing plunge into the Han River, Olesen also manages avoid the clichéd ending many a reader familiar with the tropes of English-language writing on modern South Korea will think they see coming. Such a fate does befall a character in David Smith’s “Long Road,” though not the main character, a fast-food delivery driver named Ju-ho given to bitter reflection on his hardscrabble existence. He envies Jin-yeop, a friend from his soldiering days — Jin-yeop with his “his education around Gangnam, his family trips in America, and on top of everything, his graduation from Yonsei University. When they parted ways after the military, Jin-yeop was already set up with his career at a major company, and Ju-ho slumped back to Seoul to scrounge together whatever life he could.”

Yet it is the low-living Ju-ho, not the Jin-yeop the veritable umchina, who ends the story with better prospects, not to say good ones. Like most the stories in A City of Han (whose title seems to refer to the blend of sorrow and resentment thought of as characteristically Korean), “Long Road” expresses the kind of vicarious frustration with the inequality and conformity of Korean society on which the Ho-joons and Song-euns of the world tend to be happy to hear Westerners expound. Gord Sellar’s “Sojourn,” the book’s final story, does the same, but in a manner heightened by a near-future setting in which certain human beings are X-Men-style mutants possessed of superhuman powers. Trevor, a Canadian hagwon teacher (apparently this Korea still suffers from English cancer), is one such “deviant,” and like all his kind in Korea must conceal his superhuman ability — he can perceive and alter the biological workings of any organism at a level of detail unimaginable even to microbiologists — lest he be deported.

Though not subject to deportation, Trevor’s young student Soo-jin must for the same reason keep a lid on her telekinesis. “Wasn’t it different where he came from?” she thinks as she regards her teacher. “Weren’t ‘deviants’ called ‘gifted’ there? Her mom had said they weren’t taken away by the police, or put in special schools, or forced to do anything they didn’t want except register with the government.” One day her power gets away from her and she levitates a pencil box in class, causing the hagwon’s director to report Trevor to the authorities: “she’d assumed he had to be the deviant, that it had to be the foreigner in the room.” When police officers show up and give chase, he and Soo-jin soar up, up, and away, away from Korea and toward Canada, where it’s “okay to be different.” It dramatizes a range of complaints I’ve heard from English teachers here, from the suspicion they feel falls automatically upon them due to their being foreign to what they see as the “stifling” of kids who don’t fit society’s prescriptions.

All this can instill in Westerners a tendency to romanticize (as well as recklessly exaggerate) the freedom and individuality on offer back in the countries they came from. But at the same time, as Sellar has Trevor acknowledge, “practically every expat he knew in Korea had, on some level, come here to escape something back home.” Perhaps that’s true, to one degree or another, of expatriates in any place and time, or at least those willing to live under that label and the sense of permanent temporariness and actively maintained cultural distance that attends it. Notably, however, apart from that paragraph of “Sojourn,” nowhere else in A City of Han does the word expat (or even expatriate) appear — unless you count the front cover, with its subtitle promising “stories by expat writers in Seoul and other cities of South Korea.” But as the book itself suggests, the day may come when Western writers here see themselves as something more.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Hagwon Horror Stories: Kevin M. Maher’s English-Teaching Expat Novel No Couches in Korea

Short Skirts and Flying Chopsticks: Revisiting the “Worst” Essay on Korea, 10 Years Later

French Nobel Laureate J.M.G. Le Clézio’s New Novel of Korea, and the Love of Korea That Inspired It

When Korea Expats Podcast (or, the Pleasures and Sorrows of Teaching English)

Bright Lies, Big City: Korean Authors and Seoul

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.