Americans in general don’t emigrate at particularly high rates, but some Americans in particular are given to declaring, in moments of frustration, their imminent move to another country. Often that country is Canada, possibly because of the vague impressions it inspires of a more humane and orderly civilization (and more probably due to linguistic and geographic convenience). Sometimes that country is Sweden, which to certain observers represents the fullest possible realization of political and economic idyll in this world. But as enthusiasts of crime fiction know, not quite all can be well in the land that produces such great quantities of what has been labeled “Scandi noir.” In the United States — a nation whose readers’ appetite for crime fiction seems downright insatiable — that bleak, society-indicting genre is most popularly represented by Swedish journalist-novelist Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and its two sequels.

With the final book of that trilogy having been published in English translation more than a decade ago, and Larsson having died years before that, the publishing industry has cast around for other societies capable of producing counterintuitively stark and savage crime fiction. Certain well-established Japanese mystery novelists, like Hideo Yokoyama and Natsuo Kirino, have ridden the waves of this boom. But over the past decade here in South Korea, a number of younger writers have been working so productively and so squarely in the realm of crime fiction that they’ve made their country almost too likely a candidate to run with Scandi noir’s torch through the English-reading world. Earlier this month, Yun Ko-eun’s The Disaster Tourist, won the UK Crime Writers’ Association Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger award, which over the previous decade had gone three times to Scandinavian novels, all of them Swedish.

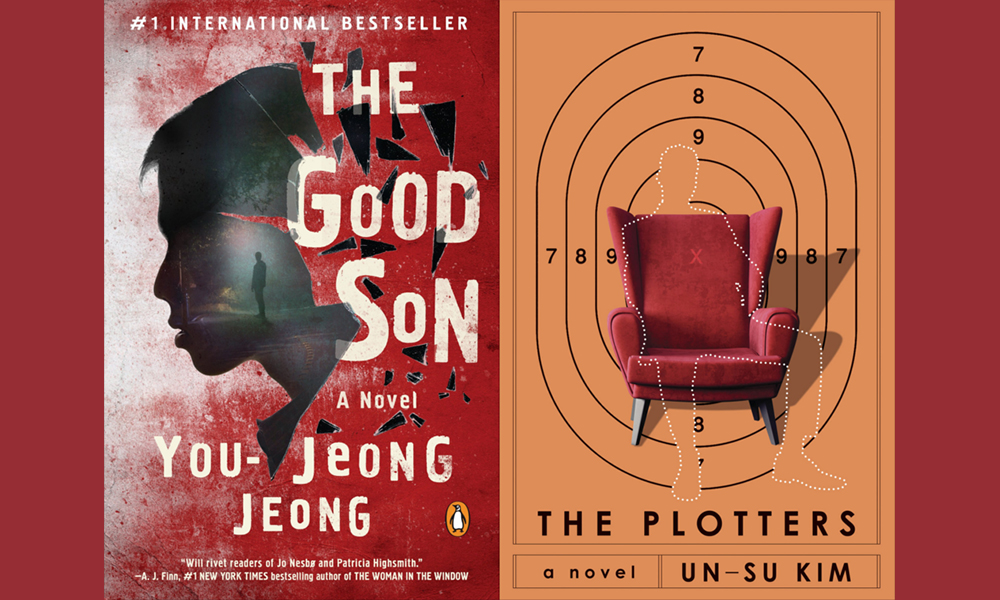

If an international Korean literary crime wave is indeed afoot, an examination has to proceed from an earlier point in time. We must go back at the very least to 2019, when more than one high-profile, critically acclaimed Korean crime novel began appearing in English per year. 2019 saw the publication of both Jeong You-jeong’s The Good Son, translated by Kim Chi-young, and Kim Un-su’s The Plotters, translated by Sora Kim-Russell. In each book the protagonist is a killer, hardly an out-of-line choice for the genre, but the style of the killings themselves could hardly be more different. The Plotters tells the story of a professional hitman who has hardly known any other form of existence; The Good Son, of a 25-year-old layabout (a “NEET”) who wakes up to find his mother slain in the next room, with all signs pointing to him as the culprit.

When it came out here in 2016 (titled 종의 기원 or The Origin of Species, not to be confused with Kim Bo-young’s recent collection), The Good Son became an inescapable hit. Considering Kim Sagwa’s Mina back in 2009, I wrote of my curiosity about why Korean children almost never kill their parents. It’s not that I expect a nationwide vogue for patricide and matricide, but that the combination of the pressure exerted by parents on children and the penchant for explosive rage attributed to Koreans by Koreans themselves struck me as a ticking time bomb. Jeong quickly establishes her young protagonist Yu-jin did indeed kill his mother, an idea that seems to have struck a resonant chord indeed with domestic readers. But the murder, as she crafts it, turns out to have been the result of nothing so simple as the son’s having been pushed too hard.

However dark and complex things look to begin with, they can always grow darker and more complex: this, so I’ve gathered, is the rule with crime fiction, whatever its country of origin. Deepening the darkness and complexity makes great demands on the author’s ability to provide information to and withhold information from the reader, sometimes alternately, sometimes simultaneously. On that level, this genre is a pure test of storytelling ability, and in The Good Son Jeong puts her own to the test on a spare stage. “I was the investigator interrogating the criminal,” says Yu-jin, also the story’s narrator. “But the two were one and the same, the criminal had a slippery relationship with the truth, and his memory was spotty.” His problems with recollection owe to the medication he takes at the behest of his psychiatrist aunt, ostensibly to treat epilepsy, but really for reasons darker, more complex, etc.

The Good Son has been acclaimed as an exploration of the mind of a psychopath. As they watch the deaths attributable to Yu-jin pile up, few readers could disagree with that framing. Or at least couldn’t until they consider the narrative proposed by Yu-jin himself, that of a promising if emotionally disengaged young swimmer flimsily suspected of insanity, then deceptively medicated and manipulated to the point of being, in effect, made a murderer. And though he does display a kind of heroism, at least insofar as he brazenly extricates himself from one hopeless-looking situation after another, he remains unambiguously the kind of individual most of us would rather see removed from society. So, perhaps, is Reseng, the 32-year-old protagonist of The Plotters — or he would be if he lived among normal people rather than the world of political contract killing into which he was practically born.

Found abandoned in a garbage can as a baby, Reseng was adopted by an organizer of assassinations, or “plotter,” known as Old Raccoon. Raised to kill, he came of age amid an industry in transition owing to the political transformation of South Korea. “Ironically, the overthrow of three decades of military dictatorship and the brisk advent of democratization had led to a major boom in the assassination industry,” Kim writes. “Under dictatorship, assassinations were clandestine operations carried out in secret by a small number of plotters, hitmen expertly trained by the government or the military, and highly experienced and trustworthy contractors.” But the new democratic administrations “sought the trappings of morality. Maybe they thought that by stamping their foreheads with the words It’s okay, we’re not the military, they could fool the people. But power is all the same deep down, no matter what it looks like.”

The relatively genteel brutality of Old Raccoon, who maintains a government library as a front for his real operation, is falling into irrelevance. A younger plotter called Hanja, a “dandy with a Stanford MBA” who “secretly cultivated his own team of plotters and mercenaries under the cover of a perfectly legal security company,” represents the new guard. And it is the slick, Gangnam-style Hanja against whom the more rough-hewn Reseng (whose hobbies include binging on canned beers for a week at a time) eventually finds himself locked into mortal conflict. The elaborate series of events that leads to their showdown begins not with a killing, but with a hesitation to kill: the book opens with Reseng fixing the crosshairs of his rifle on just one of his many assigned targets, an old man living practically off the grid in a mountain cabin, but finding himself unable to pull the trigger.

When his dog spots Reseng, the old man takes him (or decides to take him) for a hunter and invites him to spend the night. Only the next morning can Reseng summon the will to carry out his orders, and only after that does he find out his target’s identity: a former North Korean general who defected and spent decades thereafter drawing up the kill lists for South Korea’s military government. Curiously, one of the editions of The Plotters‘ English translation I’ve seen excises the parts about his Northern provenance entirely; it also simplifies other instances of Korea-specific detail, reducing “banmal, the familiar form of speech,” for example, to “the informal register.” There is, I supposed, an argument to be made for this sort of thing: to wit, that in genre fiction in general and crime fiction in particular, nothing must be allowed to “slow down” the story.

Even in a crime novel, I lament missed opportunities for the reader to learn more about Korea, and especially the Korean language. So I appreciate that neither Kim Chi-young’s translation of The Good Son or Sora Kim-Russell’s of The Plotters read as if excessively universalized. Some Westerners will take Jeong’s references to a “Hakuna Matata” cellphone ringtone and a matinée screening of The Bucket List to be localized substitutions, when they’re just the kind of dubious artifacts of American popular culture often encountered in everyday Korean life. In the main, what The Good Son conveys about the society in which it takes place, it conveys between its scenes of throat-slashing and evidence concealment: depictions of educational structures, family dynamics, and living space, that last being the rare two-story apartment Yu-jin, his mother, and his adoptive brother occupy in a new town still incompletely built on the outskirts of Incheon.

Life in such a marginal place, the likes of which crime fiction has no end of use, is a kind of exile: the family once lived in Seoul, but since a darkly hinted-at incident years before, they’ve been tossed farther and farther from the center of things. Reseng of The Plotters, for his part, may live in the capital, but his work takes him to a host of unspecified run-down urban warrens and dingy provincial towns. Early in the book, he’s sent to a port city on the skids since the colonial period (Mokpo, I strongly suspect) to take out a call girl said to have run afoul of men in power. His impulsive decision to grant her a painless death marks another departure from orders; similarly, Yu-jin enacts an at-first minor rebellion against the tight controls imposed on his own life by secretly going off his physically enfeebling medication.

Both Yu-jin and Reseng are already killers when their respective stories begin. But neither had much choice in the matter, the killer instinct having been identified in them in childhood by an adult: an adult who attempted to suppress it in the former case, and one who attempted to cultivate it in the latter. Yet both Yu-jin and Reseng also end up going rogue, wreaking planned-under-pressure havoc in differently self-annihilating ways. Set in a high-end department store, The Plotters‘ chaotic finale reads as if written expressly for conversion into an action-movie screenplay — as, unfortunately, does much else in the book, at least by comparison to the chillingly pitched interior monologue of The Good Son. But each novel’s ending does represent one of the two of the major possible fates for the crime-fiction protagonist: the blaze of glory, or a “disappearance” (with the possibility of reappearance in a sequel).

Violent criminals in the real Korea seldom seem to manage either, tending by their very nature toward impulsiveness and incompetence. Accounts of violent crime in Korean news bear this out, less frequent though they are than in American news. For Americans familiar with Korean society, that difference alone is enough to motivate a declaration of intent to move here. But for Koreans steeped in the tradition of condemning Korean society, a tradition of which all kinds of fiction heartily partake, the country’s relative absence of visible everyday crime belies a rotten core. They would surely agree with the ill-fated character in The Plotters who says that “you need more than freeways and skyscrapers to be a developed country. You have to develop the right mindset first, dammit!” They’d also agree when Kim writes that “power is all the same deep down” — adding only that, in Korea, it’s even worse.

This is the first of a three-part series on Korean crime fiction. The second is here.

Related Korea Blog posts:

The Making of a Korean Monster: Kim Sagwa’s Bloody High-School Novel Mina

We All Had a Hard Time Back Then: Lee Seung-U’s The Private Lives of Plants

Let’s Get Out of Here: The Bitter Korean Neorealism of Yu Hyun-Mok’s Aimless Bullet

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his website, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.