This is the second of a three-part series of essays on Korean crime fiction. The first part, on Jeong You-jeong’s The Good Son and Kim Un-su’s The Plotters, is here.

Whatever its country of origin, crime fiction prizes murderers. Even more suited to the demands of the genre are serial killers, murderers who — according to most of the definitions available — kill three or more people on two or more separate occasions. Though the protagonists of both Jeong You-jeong’s The Good Son and Kim Un-su’s The Plotters do meet these requirements, neither quite fit the cultural image of the serial killer, at least as understood in the West. In the former book, the young ex-athlete Yu-jin performs three separate murders, though all within a short span of time and for the most part impulsively. In the latter, the more mature Reseng is a professional assassin, raised from orphanhood to carry out contract hits for the government. Much truer to the serial-killer stereotype is Kim Byeongsu, the 70-year-old narrator of Kim Young-ha’s Diary of a Murderer.

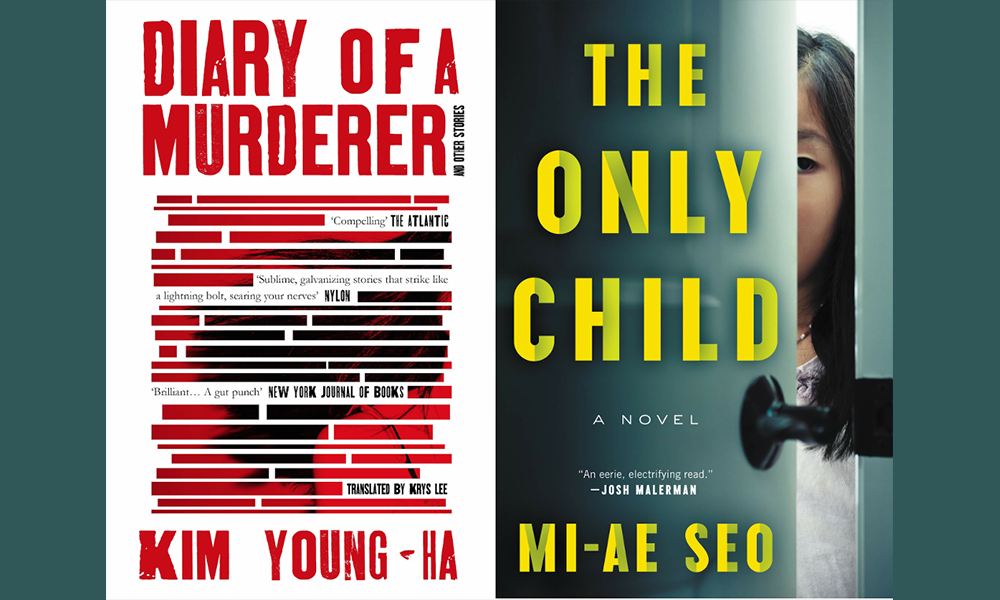

Published in Krys Lee’s English translation last year, Diary of a Murderer consists of what its title promises. The title itself has, however, lost something in translation; more faithful to the original (살인자의 기억법) would be “Mnemonics of a Murderer,” which I once heard suggested by another American fan of Korean literature. For Kim Byeongsu writes his diary as an aide-mémoire, having been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease of a rapidly increasing severity. Its entries register his fears not just for his own state of mind, but for his adopted daughter Eunhui and her recent engagement to a man named Pak Jutae. Recognizing Eunhui’s fiancée as one of his own homicidal kind, Kim Byeongsu resolves to emerge from retirement: “I’ve decided on a final goal before I die,” he writes in his diary. “To kill Pak Jutae. Before I forget who he is.”

Living with Eunhui in the foothills of a remote village below the North Korean border, Kim Byeongsu has put more than one pursuit behind him by the time the story opens. “It’s been twenty-five years since I last murdered someone,” he writes in its opening lines, “or has it been twenty-six?” He’s also closed the veterinary practice that constituted his public-facing career. (“It’s a good job for a murderer. You can use all kinds of powerful anesthetics.”) And no longer does he write poetry, a literary avocation — and in Korea, not an uncommon one — taken up through classes at the local community center. Writing what he knew, he composed visceral poems that drew praise from his instructor, but audience reaction was beside the point: “The way you feel about writing poems that no one reads and committing murders that no one knows about is not that different.”

A self-styled man of letters, Kim Byeongsu makes reference in his diary to Montaigne, Borges, and Nietzsche; he quotes from the sutras, suggesting Buddhist beliefs. Here we have a serial killer with a wider capacity of mind than most, albeit a mind slipping away even as we read his words. This makes him an unreliable narrator, though one increasingly convinced of the truth of his own perceptions; that his voice and his voice alone conveys to us the gap between those perceptions and reality ever widened by his intellectual dissolution speaks to the skill of the author. Kim Young-ha, whose novels in translation I perviously wrote about in 2013, comes to crime fiction as something of an interloper, having made his name as one of Korea’s most famous novelists with a Kubrickian penchant for genre-hopping, previously following an existential noir with a spy thriller with a piece of historical fiction.

At novella length (published in English alongside three short stories), Diary of a Murderer is more readily adaptable than Kim’s other books, and indeed a film version directed by thriller-and-horror specialist Won Shin-yun came out in 2017. In English it appeared under the title Memoir of a Murderer, maximizing the potential confusion with Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder (살인의 추억). That acclaimed movie is also referenced in Kim’s novella, and both works take as a theme the changes that swept Korean society in the transition from military dictatorship to democracy, down to the ground of crime and punishment. Memories of Murder portrays homicide investigation in the disordered Korea of the 1980s as a Sisyphean exercise in futility. “Back then there was no such thing as DNA testing or surveillance cameras,” remembers Kim Beyongsu. “Thousands of cops wielding batons climbed up the wrong mountains to investigate.”

“Those were good times,” when the Republic of Korea’s law-enforcement showed concern for fifth columns and practically nothing else. “While everyone was trying to catch the phantom that was communism, I was doing my own hunting. An official announcement about a man I killed in 1976 declared than an armed spy had murdered the man” and presumably fled back to the protection of the North’s “puppet regime.” No such references to Korean history or politics appear in Seo Mi-ae’s novel The Only Child (잘 자요 엄마), whose English translation by Jung Yewon was also published last year. In fact, apart from the names of its characters and the highly specific Seoul geography they inhabit (“as Sangwuk climbed over the Muakae Hill and drove onto Moraenae Street from the Hongje three-way intersection, his phone rang”), most of its story might as well take place in the West.

Here and there, however, Seo scores satirical points against certain aspects of modern Korean society, such as its abject over-valuation of any connection to the United States, no matter how tangential. The novel’s protagonist Yi Seonkyeong, a criminal psychologist and university lecturer, becomes a campus celebrity as soon as word gets around that she’d trained at the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit — once, for a two-week seminar, buy why split hairs? This gets her nicknamed “Clarice,” and The Silence of the Lambs isn’t even the book’s most prominent Western pop-cultural reference. Seonkyeong soon finds herself face-to-face with a Hannibal Lecter of her own, a serial killer named Yi Byeongdo (no relation, or least none established in this book). Having been made into a killer by his mother’s abuse, as Seo tells it, he lives on tormented by the Beatles song she always used to sing to herself.

That song is “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” one of Paul McCartney’s most reviled compositions. A “cheery tale of a homicidal maniac,” as music critic Ian MacDonald calls it in his study Revolution in the Head, it “represents by far his worst lapse of taste under the auspices of The Beatles.” Byeongdo recalls that one member of the band was shot to death, then adds, “If I’d been born a bit earlier, or I’d had a chance to meet them, I would probably have killed them with my own hands. I would’ve really liked to ask then why they made a song like that.” Whatever its offenses, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” isn’t the kind of song a Western reader expects to come across in a Korean crime novel — though one who’s spent enough time in east Asia knows how oddities from the other side of the world can attain inexplicable popularity here.

As Seo tells it, however, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” is even more obscure in Korea than it is in the West. “Seonkyeong was somewhat surprised that Yi Byeongdo knew the song,” she writes. “Neither Seonkyeong nor he was of a generation that had easy access to the song,” but Seonkyeong happens to have had a Beatlemaniac advisor while studying abroad in America. This provides her with one point of connection to the infamous murderer, as does her mother’s early death, albeit under different circumstances from that of Byeongdo’s. “You don’t know, do you? What it feels like to kill your own mother?” he asks Seonkyeong during one of their interviews in his maximum-security confines. “You don’t realize at first. It happens in an instant, like a lightning strike. You do it with your own two hands, but… you’re nothing but an instrument. Yes, as if someone made you do it.”

Those words could also describe the matricidal experience of Yu-jin in The Good Son. In Byeongdo’s case, the act, committed as a teenager, planted in his psyche a serial-killing seed that would sprout, and prolifically, fifteen years later. Kim Byeongsu also began his murdering career with an abusive parent, not his mother but his father, and with the involvement of his long-suffering mother and sister as well. It was after slaying the young Eunhui’s parents decades later, as he tells it, that he decided to adopt her. Death puts Seonkyeong, too, into a non-traditional family arrangement: her husband’s eleven-year-old daughter Hayeong moves in with them when a house fire kills the grandparents with whom she’d been living since the passing of her own mother, Seonkyeong’s husband’s ex-wife. As in most crime fiction, these deaths must have darker, more complex stories behind them, only to be told over subsequent chapters.

The photograph of a young girl peering through a cracked-open door on The Only Child‘s cover primes the reader to perceive Hayeong as a threatening figure. And so, much of the time, she proves to be, given to unpredictable emotional outbursts and minor but escalating acts of violence. But Seo writes her as having come by it honestly, subject as she was first to the machinations of a mother who saw her only as a tool to win back her ex-husband, then to the inattention of grandparents mainly interested in cashing her father’s child-support checks. Many of Seonkyeong’s strenuous attempts to integrate her into the household do more harm than good, though when Seo shifts into the first-person voice of Hayeong — chapters that reveal a fuller character than the singleminded child-psychopath we might have expected — she brings her quite close to warming to her new stepmother.

Alas, in the reality Seo has constructed, no maternal relationship of any kind can end well. This holds as true for Seonkyeong and Hayeong as it does for the killer Byeongdo, who’s first motivated to contact Seonkyeong when a glimpse of her reminds him of the woman who took him in and became a kind of surrogate mother after he murdered his biological one. Two of these three characters get their fates sealed when they converge, in one of the final chapters, on a dark and stormy night. The movie-of-the-week dénouement that ensues leaves matters just open enough for a sequel, and as the back-flap copy states, “Film rights for The Only Child have been optioned by Carnival Films.” To an extent, the feel of having been written for adaptation compromises the work as a novel, though the same could presumably be said of much Western crime fiction as well.

The crime novel, as the genre’s Western fans know it, is in Korea a borrowed form. (But then, in a country with far more established short-story and poetry traditions, so is the novel itself.) Nevertheless, as the books covered in these essays demonstrate, Korean crime fiction in translation has begun to manifest distinctive characteristics, not least its prominent use of relationships both familial and quasi-familial. As represented in Korean literature and film in general, these relationships are disproportionately liable to strike Western viewers as unhealthy, even traumatic, especially those involving what’s often academically referred to as “the figure of the mother” (as essayed by Bong-hoon Ho, with characteristic extremity, in his film Mother). But trauma, as the substance of literary and genre fiction alike, has become a hot property in publishing, generating both sales and acclaim, and Korea certainly has a deeper well of it from which to draw.

Part three of this series is here on the Korea Blog.

Related Korea Blog posts:

The Korean Literary Crime Wave: Jeong You-jeong’s The Good Son and Kim Un-su’s The Plotters

A Korean Literary Superstar Tells His Countrymen Why to Read

The Making of a Korean Monster: Kim Sagwa’s Bloody High-School Novel Mina

We All Had a Hard Time Back Then: Lee Seung-U’s The Private Lives of Plants

Let’s Get Out of Here: The Bitter Korean Neorealism of Yu Hyun-Mok’s Aimless Bullet

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.