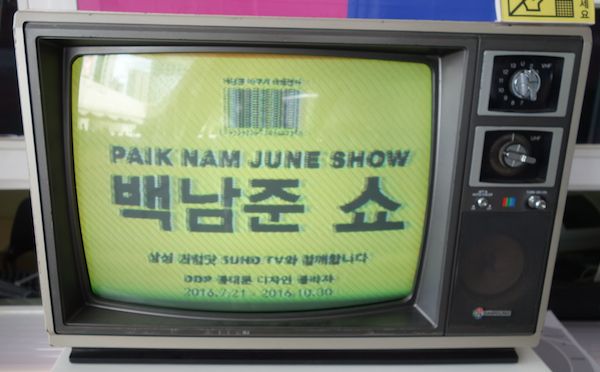

Video monitors started appearing on Seoul’s subway trains long before I arrived here. More video monitors — or, to be precise, old televisions — started appearing on those video monitors a few months ago, announcing a big show of the work of video artist Nam June Paik. (Paik made his name in the West, literally, with not just unconventional Romanization but a Western-style re-ordering that put his given name first and family name second.) The straightforwardly titled Paik Nam June Show (백남준 쇼), which runs through October at Seoul’s Dongdaemun Design Plaza, commemorates the tenth anniversary of the death of the most creative old-television enthusiast ever to live, as well as, for a time, the most famous Korean artist — and quite possibly the most famous Korean — in the world.

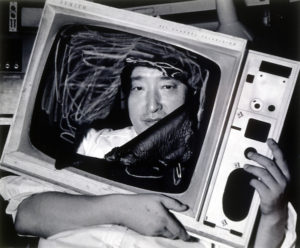

“I start in 1960, first time television sets become cheap, become secondhand, like junk,” said Paik in a 1975 profile by New Yorker art critic Calvin Tomkins. “I buy thirteen secondhand sets in 1962. I didn’t have any preconceived idea. Nobody had put two frequencies into one place, so I just do that, horizontal and vertical, and this absolutely new thing comes out.” He refers to his discovery that manipulating the electronics television sets use — or then used, anyway — to produce an image could produce, in an unpredictable fashion, another, stranger image.

This led to his creation, with Japanese engineer Shyua Abe, of the more controllable Abe-Paik Video Synthesizer, and ultimately to his status as the father of video art, builder of television robots, television cellos, television-watching Buddhas, and television maps and flags of the United States of America. While other artists began to use video around the same time he did, when the gear came down in size, down in price, and out of the studio, none displayed quite the same intensely zealous interest of the early adopter.

Paik’s embrace of the moving image as displayed on consumer electronic devices now looks prescient, as do several of the futuristic ideas upon which he speculated. He even coined, in a 1974 proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation (a major source of funding for early video artists), the term “electronic superhighway,” imagining a time in which “we connect New York with Los Angeles by means of an electronic telecommunication network that operates in strong transmission ranges, as well as with continental satellites, wave guides, bundled coaxial cable, and later also via laser beam fiber optics.”

Tomkins, in the New Yorker profile, wrote of Paik’s vision for a familiar-sounding “’global university’ — a place where vast quantities of up-to-date information on every conceivable subject can be stored, with computers to provide instant retrieval, so that a student of any age can pursue his own education at his own pace.” And so it feels highly appropriate to see him celebrated in his homeland, a place whose high internet speeds and rates of connectivity get it routinely described, in the 21st century, as the most wired country on Earth.

His countrymen tend to seize upon each new device as soon as it comes to market, and even among Koreans close to Paik’s own generation (he was born in 1932, with the end of the Japanese colonial era still nowhere in sight), one sees much less of the kind of technological foot-dragging common among older people in the West. American youth might just have got around to teaching their grandmothers how to use a smartphone; in Korea, grandma’s already in line for the next one. Those screens on the subway already seem superfluous; who can get bored enough to watch the advertisements they play between station announcements with a personal screen in the palm of their hand?

Often enough I’ve looked up on a subway ride to see literally every other passenger absorbed in what Koreans call their “handphone,” texting, gaming, and scrolling through page after page of one kind of information or another. Sometimes, on these occasions, I’ve looked up from my own, an iPhone so bashed and so many generations behind that, here, its ownership almost violates some sort of social taboo. Besides, for every (newer) iPhone user in Korea, several have a local model made by Samsung or LG instead — companies that also manufactured more than a few of the many screens glowing from within the works on display at the DDP.

Paik’s sculptures, made of not just wood-grained and dial-controlled sets of long-forgotten brand but paint, neon, cameras, and many kinds of non-televisual junk, present what museum professionals call a “preservation challenge.” Peer around the back of the hulking, friendly-looking robots that greet you as soon as you enter, and you see that someone has hollowed out the bulky, even-then-obsolete televisions that compose their bodies and mounted outward-facing flat-panel displays of various sizes up against the glass.

Paik could hardly have known, putting his television robots together in the 1980s when the Korean economy still grew itself — and with astonishing rapidity — through industries like shipbuilding, that flat-panels (surely a term soon to go the way of “computerized” and “portable”) would do much to make his homeland a global economic power. Had by that time spend a decades away from that homeland, in a kind of exile. “Because of South Korea’s stringent military-conscription law,” Tomkins wrote in 1975, “he could technically be arrested as a draft dodger if he ever returned.”

He’d left with his family in 1950, after their luck at home finally ran out — a luck that came in large part due to his merchant family’s open collaboration with the Japanese occupiers. They managed to retain their status for a time even after liberation, albeit not for long. “Growing up in a very corrupt family in a very confusing time,” he later said, “I learned how to survive, and survive well.” Paik’s family settled in Japan, where he graduated from the University of Tokyo before moving to Germany to study avant-garde music composition.

The Japan connections continued throughout the rest of his career and life. He and Yoko Ono both once counted themselves as members of the Fluxus artistic movement (there exists a later photograph of Paik, Ono, Shuya Abe, and John Lennon standing in front of a wall of televisions). He married Shigeko Kubota, a Japanese colleague in video art. His work incorporated many pieces of Japanese technology, like Pioneer’s LaserDisc media and Sony’s Watchman handheld televisions, still flickering away after all these years.

Paik eventually made it back to Korea in 1984, writes scholar Robert Fouser in “Having Fun with New Toys: Nam June Paik and the Aesthetic of Jaemi.” This homecoming “started a broad shift in Paik’s work. Despite the immense change in Korea during the intervening 35 years, the jaemi of the streets of Korea brought back memories of the street jaemi that Paik had known as a youth.” The what? Fouser quotes the Minjungseorim’s Essence Korean-English Dictionary‘s definition of jaemi (재미) as “interest; amusement; enjoyment; fun.”

Artistically, it means that “a work or performance needs to entertain and stimulate an audience through amusement and fun. Humor, sarcasm, and visual stimulation all qualify as jaemi,” which also “contains the element of surprise and keeps audiences slightly off balance with jocular spontaneity.” According to Fouser, “jaemi best summarizes the dominant aesthetic of Korean modernism,” and to my mind also summarizes the enduring appeal of Paik’s art. His robots, grinning or raising a glowing arm in salute, exude, and possibly define, late-20th-century techno-whimsy.

Even his more austere pieces, such as those Buddhas staring eternally into their own motionless images reflected by television screens, draw chuckles from their viewers. As for the element of surprise and jocular spontaneity, Paik began using that well before he entered the secondary market for TV sets, driving nails into pianos on stage (one critic called him “the world’s most famous bad pianist,” a title in which he delighted), snipping ties and shirttails with scissors off of it, and, with the cellist Charlotte Moorman, staging topless or otherwise scandalous musical performances (some of which had her wear a “TV Bra” of Paik’s invention).

Despite his start in the avant-garde, his work has retained plenty of relevance in our time when the term “avant-garde” itself no longer means much of anything, and when new technology, especially new technology related to the display of images, no longer impresses on anything like as deep a level as it once did. But to the younger generations who’ve started to regard VHS cassettes as nostalgia objects, images out of a cathode ray tube look compellingly unusual and rich with imperfection. Twenty years ago, sheer availability had rendered the household electronics Paik made his signature materials almost invisible. In the 21st century, they’ve regained the something of the strangeness — now accompanied by echoes of the past instead of messages from the future — he must have sensed when first he discovered their artistic potential.

Call it a kind of “authenticity,” an aesthetic quality much prized by the retromaniac hipsterism of the West, a movement that has so far shown few signs of penetration into the neophiliac un-irony of modern South Korea. Though possessed of a formidable sense of humor, Paik’s work has never exuded irony. In that, the Japanese-educated artist who spent most of his life in Europe and the United States — as well as the Buddhist who never drank, smoked, or drove — represents the sensibility of his people more than he might at first have appeared to.

Korea almost automatically celebrates its native sons and daughters who’ve won acclaim for themselves abroad, and thus acclaim for their country, no matter how aberrant their behavior or unfashionable their creations. Fouser sees Paik, who accomplished what no other Korean artist could by “influencing the West with a subverted view of its own culture,” as “a combination of Paik the inheritor of Korean modernism and Paik the inheritor of bourgeois careerism.” Having drawn his first feelings of “techno-jaemi” from listening to the radio, riding in the car, and playing the piano in his youth, he went on to observe his family “use its wealth and power to maintain the status quo after liberation,” learning that “systems have to be manipulated for self-protection, and that ideals matter less than practicality.”

Fouser credits Paik’s use of jaemi as having “helped to desanctify art and make it fun again.” Asked by Tomkins why he doesn’t make boring art, Paik himself replied: “I come from very poor country and I am poor. I have to entertain people every second.” Not that you’d know, strolling through Zaha Hadid-designed Dongdaemun Design Plaza and into the Paik Nam June Show, that either Paik or South Korea came from poverty. It even ends in with a genuine spectacle, in a room built for a huge sea turtle made entirely out of 1990s-style television sets, all boxy yet rounded. Every few minutes, much newer projection technology, still impressive in itself, sends the entire floor around the electronic reptile through a rippling metamorphosis, from solid to liquid, concrete to abstract.

From there you exit straight into another room containing (this being Korea, after all) a pop-up coffee bar and a display of all the Nam June Paik merchandise available for purchase. The hallway outside that contains a video work built in tribute to Paik by the media artist Choi Jongbum — making use, the signs tell us, of the latest models in Samsung’s lineup of “quantum dot display” ultra high definition TVs — and a lounge area bristling with cables loungers can use to charge their handphones. They might well need to, having drained their batteries snapping selka (샐카, or the Korean version of “selfie”) with friends standing beside Paik’s robots, or in silhouette against the colorful video collages of his not-quite-regular grids of monitors.

All this does little to actively refute the notion, long held by Paik’s critics without seeming to bother the artist himself, that his work wasn’t quite serious, that it was a little too much fun. As the standard translation of “fun,” jaemi, sound like a highly specialized cultural concept though it may, is one the very first vocabulary words a student of the Korean language learns. If you want to say you enjoyed something, you say “Jaemi isseosseoyo,” literally something like “There was fun.” If you want to say you didn’t enjoy something, you say “Jaemi opseosseoyo,” or “There wan’t fun.” This becomes something of a crutch later on, when people begin to expect more specific responses, but later in the day I’d seen the Paik Nam June show, when a friend asked how it was, my response — jaemi isseosseoyo — sounded a great deal more meaningful than usual.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Writing About Korea, in Korean, for Koreans — as an America: an Interview with Robert J. Fouser

Why Korea Needs Alain de Botton (and Why Alain de Botton Needs Korea)

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.