When last I lived in Los Angeles, I met a Korean friend for coffee every week. After a few months of doing so, I noticed that she always, without exception, ordered an Americano, so I asked why. She explained that, if she simply ordered a coffee — or keopi (커피) — back in Korea, she might well wind up with something made from a powder. And so, now that I live in Korea myself, I follow the very same rule. As it happens, I already had plenty of experience adhering to it in Mexico, another piece of that globe-spanning territory I like to call “Nescafé country.”

Older generations of the Korean population remain quite influential within their country, most notably in their unflagging support of something called dabang keopi (다방 커피), a foul mixture of instant coffee, copious amounts of sugar, and often artificial creamer named for the old-style coffee houses that first served them. But apart from the few establishments that, over the decades, have become attractions again through sheer persistence combined with an unwillingness to change their décor, most dabang have given way to what we would now call second- and third-wave coffee shops, seemingly none of which permit a spoonful of Nescafé — or such home-grown brands as Maxim or French Café — on the premises.

Famed Los Angeles food critic Jonathan Gold helpfully breaks down the “waves” as follows: “The first wave of American coffee culture was probably the 19th-century surge that put Folgers on every table, and the second was the proliferation, starting in the 1960s at Peet’s and moving smartly through the Starbucks grande decaf latte, of espresso drinks and regionally labeled coffee. We are now in the third wave of coffee connoisseurship, where beans are sourced from farms instead of countries, roasting is about bringing out rather than incinerating the unique characteristics of each bean, and the flavor is clean and hard and pure.” And as with most things that make it across the Pacific, Korean coffee culture has followed the same path, only much faster.

Korea’s very first Starbucks coffee shop appeared in front of Seoul’s Ewha Womans University in 1999. Since then, Seoul has risen to the rank of the most Starbucks-filled city in the world. The jokes we told each other in the States back in the 90s about crossing the street from one Starbucks into another have here become the plain reality, and then some. When I found a Korean teacher to meet for weekly lessons, he made it clear that I should find him not at the first Starbucks outside the subway station, but the next Starbucks, half a block down.

Many writers would use this space to lament such thorough penetration of an American chain like Starbucks into a foreign country like Korea, wringing their hands over this harbinger of a fast-arriving global commercial monoculture. But in my experience, if you really want to spot the differences between one country and another — the solid differences, those not vulnerable to fad and fashion — you have only to spend an hour or two in a local Starbucks. By holding every possible element of the customer experience steady from location to location, no matter the country, Starbucks casts those things which nobody can hold steady into stark relief. But to my mind, the most important cultural difference manifests in what you see not inside the Starbucks coffee shops of Korea, but around them: more coffee shops.

How many coffee shops? “It’s beyond imagination,” said my Americano-ordering friend in Los Angeles. And indeed, the first-time visitor to Seoul looking for a cup will find themselves surrounded, not just in any neighborhood but on most every block, with a bewildering variety of options, from international chains like Starbucks and The Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf to Korean chains like Tom N Toms, Hollys, A Twosome Place, Angel-in-us, Coffine Gurunaru, Café Nescafé (which may actually give you instant if you ask for it), Beansbins, Pascucci, Ediya, and Caffè Bene, that last known, due to its massive, Starbucks-outnumbering omnipresence, as “Bakwi Bene,” a nickname that puns on bakwi beolle (바퀴벌레) the Korean word for cockroach.

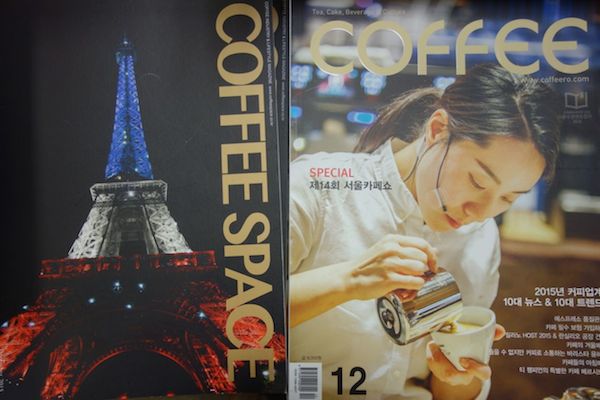

And what of the “cool” places, the independent coffee shops not replicated — indeed, not replicable — across the land, the sine qua non of urban bohemia? In America, we tend to believe, about all categories of business, that you can have one or the other, that you’ve got to choose Mom and Pop or multinational corporation, the coffee house with the old couches and the open-mic nights or the green mermaid, but in Korea they all coexist cheek-by-jowl. Alongside the chains stand a seemingly infinite number of indies, each with their own slight variations in aesthetic and specialty — some with cats, some with specialized music libraries, one with a VW van parked inside — most of the ones I’ve tried genuinely appealing spots in their own right. They’ve inspired a mini-industry of not just photo-intensive blogs but glossy guidebooks, available on the travel shelves of most Korean bookstores.

While the quantity of coffee in Korea has greatly increased over the past fifteen years, so, as any Westerner who’s lived here since the 90s will eagerly tell you, has the quality. Coffee culture, and even more so coffee-shop culture, has risen to prominence in Korean life, as evidenced by the number of magazines published here wholly dedicated to drinking and brewing the stuff as well as to the environments in which one does those activities. Many Korean coffee shops also sell beer (and some, like the beverage-portmanteau-named Coffine Gurunaru, sell wine), and a fair few, even outside Paju Book City, sell reading material, or at least sell themselves as a comfortable reading environment — or as an environment for a whole range of other activities as well.

“The coffeehouse helps manage lives,” writes Merry White in Coffee Life in Japan, a volume indispensable to someone of my particular interests. “It supports the various schedules of city dwellers, provides respite and social safety in its space, and offers refreshment and the demonstration of taste, in several senses. In its history and in its persistence, the space has shown such uses as the Japanese city welcomes or demands, and has introduced some of its own. The coffeehouse, by its very name, is about coffee, but that is the only universally defining quality — cafés are as diverse as neighborhoods, clienteles, and social changes have made them.”

As coffee has integrated itself into the fabric of Japanese cities, so it has integrated itself into the fabric of Korean ones (albeit with slightly less obsessive focus on craft and much more trendy explosiveness). Getting to know Seoul better in these first few months of living here, I’ve found myself naturally mapping it in the same way I almost automatically assemble a mental model of any city I stay in for more than a couple of weeks: by locating everything in it in relation to my favorite coffee shops.

In Los Angeles, this meant that I thought of everything in its geographic relation to such points of reference as Paradocs in Little Ethiopia, Cafecito Organico in Silver Lake, Bricks and Scones in Larchmont, Coffee Connection in Mar Vista, Kaldi in Atwater Village, Awesome Coffee in Koreatown, or the two branches of Demitasse in Little Tokyo and Santa Monica (I moved before the third opened on mid-Wilshire). I’ve sought out equivalent centers of coffee life in Seoul not just as anchors in urban space, nor just as meeting points, nor just as sources of Americanos, but above all as places to get work done — as nodes, to get William Gibsonian about it, of my globally distributed virtual office.

Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft, author of “Writing in Cafés: A Personal History” here in the LARB (and, incidentally, Merry White’s son), knows what I mean: “Cafés took me through high school, college, the itinerant odd-jobs-and-graduate-school wanderings of my 20s, through the opening moves of my career as a historian,” up through today, “to write, to read, to see friends or to get away from friends, to have strong feelings and to escape strong feelings, to pursue a crush or because of loneliness, because of inertia, because of dependency. I’ve gone because I liked people, or because I was trying very hard to like people. And of course, I’ve gone for coffee itself, but it is interesting how quickly that can drop out of the reckoning.”

Though we both do writers’ work in cafés, we also approach them as “third places,” defined by urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg as locations that “host the regular, voluntary, informal and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home and work,” the sort of “places on the corner” that offer “real-life alternatives to television, easy escapes from the cabin fever of marriage and family life that do not necessitate getting into an automobile.”

Nothing in a well-connected metropolis like Seoul would ever necessitate getting into an automobile in the first place — I often say that even if you took away everything but the subway and the coffee shops, I’d still want to live here — but something about the way Seoulites live creates an environment especially conducive to an abundance of third places. Some of it must have to do with the “beehives” in which we choose to live: not only does Seoul, like most of the major cities of Asia, lack an American-style house culture, it lacks an American-style home culture. As a result, people tend to use their apartments as little more than places to hang their hats; the city itself, in every meaningful sense, is where they live, and a healthy fraction of that living happens over cups of coffee.

Still, by no means has Korea perfected its coffee life quite yet: some chain cafés stay open 24 hours, but most of the independents don’t open until strangely late in the morning, and when you can go in, you often sit down to a soundtrack of pure K-pop, almost always played about twice as loud as you’d want to hear it even if you liked it. But I can tune that out if I concentrate hard enough on the work at hand, and I’ve more or less accommodated my schedule to theirs. I’ve even — heaven help me — started to enjoy the instant coffee that comes out of the machines installed on subway platforms. Connoisseurship varies with context, I suppose, and Seoul provides all the contexts for the enjoyment of coffee you could possibly need.

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook. Catch up on the Korea Blog’s archives here.