Robert J. Fouser first lived in Korea in the mid-1980s, going on to become a professor at Seoul National University and a high-profile commentator on Korean society, culture, and urban issues, especially the preservation of traditional the Korean houses known as hanok, one of which he purchased and restored himself. Later he lived in Japan, teaching the Korean language to Japanese university students.

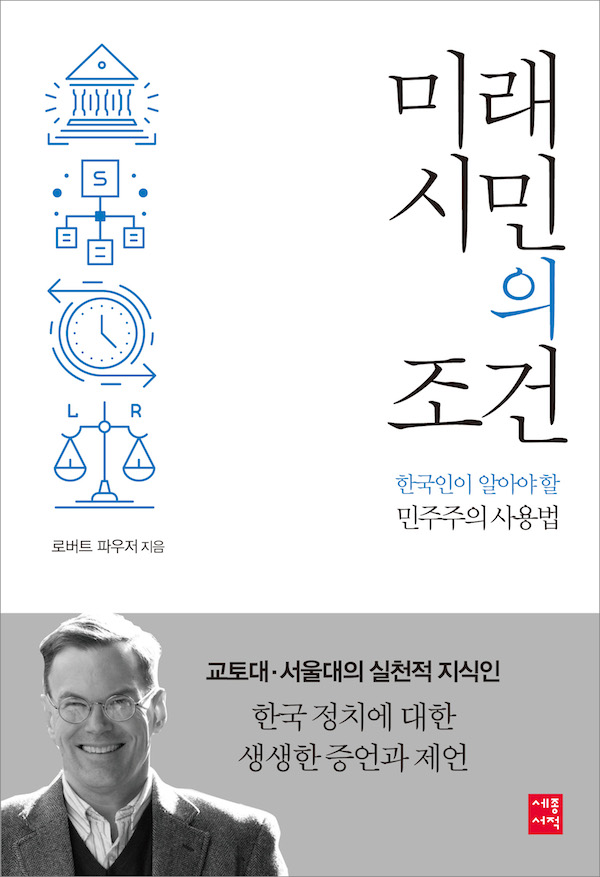

Now based again in his American hometown of Ann Arbor, Michigan, Fouser has returned to Korea for a few months to promote two newly published books he wrote in Korean: Conditions for Citizenship in the Future: A Manual of Democracy for Koreans (미래 시민의 조건) and Seochon-holic (서촌홀릭). I previously wrote about him on the Korea Blog when he led the Royal Asiatic Society on a deep Seoul walk. We sat town to talk about Korea today at Cafemoon, my coffee spot of choice by Seoul Station.

How do you describe these two books to someone unfamiliar with Korea?

Conditions for Citizenship in the Future is basically, “What is democracy? What is citizenship? How does that relate to what’s going on in Korea today?” The younger generation in Korea has lots of complaints about society. They think society is stagnant, not changing in the way they want. What the book argues they should do is participate in the democratic process, to stand up as citizens. It’s a call for younger people in Korea to take a more proactive stance in their politics. Seochon-holic is a collection of essays on things I’ve felt in Korea, my perspective on Korea. About half of it is related to urban issues, mainly preservation versus development, because I was involved in hanok preservation.

How much do you credit the younger generation’s idea of Korea as “Hell Joseon?” Is it a legitimate complaint?

From an objective perspective, it might not be, because no society can guarantee people a job, happiness, or anything like that. If you look at how younger Koreans perceive the world — that they have to be perfect, that they have to have all these accomplishments, they have to look a certain way, this pressure to promote yourself, to package yourself, to market yourself — it’s very real. That’s what’s driving the complaint: they’re expected to have all these things, but some of them take money, and there’s a feeling of not being able to get ahead.

But the Korean War left the country in a state of total material want. How did it go from that to such high material expectations?

In the ’50s, right after the war, there was stagnation, but in the ’60s, [South Korean president from 1961-1979] Park Chung-hee created the concept of “the Korean dream”: focus on industrialization and turn Korea modern, in a way into a semi-Japan. Park was familiar with the Japanese mass-scale development model because he had been a military officer in Manchuria. So he created this idea that “we all work hard, the country grows, and you get a piece of the growing pie.” For most Koreans, that turned out to be true. It actually worked. The standard of living rose dramatically as the economy developed.

You had this 30-year boom — the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, all the way to the ’90s — when the Korean dream was working for the mass of Koreans. When I first taught in 1986 in a military school, I met people my age who would tell me they didn’t have electricity at home until they were thirteen — or plumbing, heating, all these material things. So there was a hope life would improve, which started to fade after the “IMF crisis.” The country recovered after that, but the world economy didn’t really recover after 9/11, and Japan was already in the dumps. The problem now is that the older generation still has an expectation of continuous improvement, but that’s not happening. They have to come to terms with that.

We’ve also seen news story after news story about the end of the American dream. You’re from Michigan, one of the states often written about as particularly hard-hit. Do you see a similarity in the situations there and here?

The difference, of course, is that the US is still a much bigger country. The cost of housing is cheaper — outside the coasts. But yes, in essence, it’s a similar problem. To go to college you now have to take out a loan, so there’s this same perception in the U.S. that it’s hard to get ahead — not just to get ahead, but even to establish yourself. That’s driving Bernie Sanders. The young people support him. A Korean Bernie Sanders would be very possible, but who that would be, I don’t know. He came from “left field,” so to speak.

You first came to a pre-democratic Korea in the ’80s. What was it like?

It was booming at the time because of the preparation for Seoul’s 1988 Olympics. I had been to Korea for a week in 1982, but then I came for a year in 1983 and 1984, and that was when it really started to boom. Subway line number two opened while I was here, and then three and four opened. The mood of the country was “build, build, build” — but they had a dictatorship. The idea of a “good country” was not just wealth or economics, but also democracy. What is an advanced country? To a lot of Koreans in the eighties, that was a wealthy democratic society. They were on track to become wealthy, but they were dissatisfied with a lack of democracy, and that drove the democracy movement in the eighties.

South Korea has a tradition of looking for and then imitating what they consider “good countries.” It sounds a little like the South Pacific island “cargo cults” who supposedly built their own wooden imitations of runways and air traffic control towers in the hopes of bringing back the American airplanes that delivered supplies during World War II. But to an extent, it worked?

Still, the definition of a “good country” is a wealthy democratic society, that’s clear, but wealthy democratic societies also have problems. Europe has its share: the aging society thing is common there and Japan and even in the US. How do these countries deal with that? How do you make a social welfare system for an aging population? Korea is having trouble finding its own solution to these issues, whereas before the route to becoming a “good country” was very clear: instead of an appointed president, for instance, you have an election. Now they have to maintain that status and deal with other issues, which Japan is having trouble doing because of its long economic slump.

Why would Koreans want to hear a foreigner such as yourself talk about their politics and economics?

I don’t know. My editor proposed the book, and I never really asked why. From 2008 to 2014 I was a professor of Korean language education at Seoul National University. I was very unhappy there, but I didn’t tell people until recently, but that’s a long story. During those six years, I was active in hanok preservation, talking about city issues. My basic point was that “preservation versus development” is really an issue where you need a consensus about public good and private purpose: preserving something like a historic site or neighborhood for future generations versus “I own the land and want to make money off it.”

Both should be respected, and there needs to be a compromise, but I felt during my work in preservation that things were skewed toward private purpose, not so much public good. It classified me a bit as a lefty, which wasn’t necessarily my intention. That led to writing the book about politics, because people thought my perspective not as a foreigner, but from having been involved in hanok preservation, might be interesting.

Seochon, the area of Seoul referenced in the title of Seochon-holic (courtesy Robert Fouser)

You’d think Koreans would be the ones preserving their old houses, and Westerners would be the ones coming in saying, “No, no, this is all backward. We’ve got to modernize this place.” But why is the reverse true, to an extent?

There are lots of Koreans who have renovated hanok; very few foreigners have renovated a house. But Koreans may feel uncomfortable speaking out. A lot of hanok are in what are called “redevelopment districts,” which are always sensitive to speak out about. Younger Koreans especially are interested in preservation, but they might not be comfortable talking about it. My activism started around 2009, and before that, very few Koreans were interested in hanok preservation, but after that it started to change.

What’s so good about hanok?

They’re impractical from an urban-planning point of view because they’re only one floor. It’s harder to have a city with layers of tile-roofed, one-floor houses. From that point of view, they’re inefficient. But most of the hanok have been destroyed already, so I’m talking about the few that are left. They need to be preserved because they are part of the historic fabric of Seoul. There are only around 3,500 left, and that’s a very small number of houses out of the total population, so I think those houses can be preserved without affecting the density or efficient use of urban land. Some hanok are in fairly good condition and some are in terrible condition. If you have one in fairly good condition you can just renovate it, but if you have one in bad condition — really bad condition — it’s best to knock it down and rebuild another hanok in its place.

I discovered I liked hanok while I lived in one from 1988 to 1989. I liked the scale: it’s kind of small and there are lots of rooms, so you can use one room as a bedroom, one as a study, one as a junk room. Each can be adapted to a purpose. I’m back in Ann Arbor now and I have this big living room; it just terrifies me. How do I fill this monstrous space? I put up a bookcase to divide the living room into two smaller spaces. It isn’t really that big a house, but it feels huge. And of course, hanok have the hot floors, which I like.

Hanok aside, how does Seoul interest you as a city, as opposed to a Tokyo or a Kyoto or a New York or an Ann Arbor?

It’s the hodgepodge, which creates a sense of urban discovery. You have this confusion, but inside the confusion you have urban discovery. Tokyo has a bit of that too — all cities do — but in Seoul that confusion makes the sense of urban discovery a little bit more exciting. Anybody into cities will like that, if they are into cities in that mindset. If they’re into cities as organized spaces, then I can recommend other cities: Washington D.C., Paris.

I was out last Saturday, and I decided I wanted to buy some film, because I take pictures. I went to the film place I would usually go to and they were closed because it was a holiday weekend, so I went to another camera supply shop. They had film, Agfa film: black and white, it’s hard to find, I’m like, wow! This sudden urban discovery made me very happy. In Seoul, you can be in a neighborhood that looks kind of run-down, you want to take a rest, you find a coffee shop, and they have a fabulous cappuccino.

With New York, you go the Met, you go to the MOMA, you go to these high monuments of culture that you consume. At the Met, there’s a room of Rembrandts, ten on the wall. It’s a different phenomenon than Seoul. The museums here for Korean art are very good, but if you want world culture, Seoul is not your city.

You came to Korea before many Westerners did. My only reservation about moving to Korea myself was that, because so many more do it now, many of them come without much investment or interest in the country of the kind that Westerners might have in Japan. You’ve lived in Japan; is it really that different?

It is, but it’s sort of a generational thing. I when I first came, foreigners were limited in what we could do here. You couldn’t buy a house. Park Chung-hee made it illegal for foreigners to own land, and that wasn’t lifted until 1998. The only way would have been to put it in your Korean spouse’s name. There were no foreign tenured professors. If you moved to Korea in the ’80s, you had very few role models of foreigners who spent their lives here, whereas Japan had this long history of Westerners discovering it: the whole zen Buddhist thing; after the war, the Beat people who went to Kyoto; even in the Meiji era they had foreign experts. Sapporo was laid out by an American civil engineer. The foreigner in Japan is part of Japanese history. It always felt easier to establish yourself there.

Nowadays foreigners can buy land here. There’s permanent residency. If somebody’s 29 years old and they compare the two countries, those issues are not there anymore, but when I was 29 years old, Korea really was uri nara [the Korean term often used to refer to Korea, meaning “our country”]. You were here provisionally. But Koreans have done a great job overcoming that. Give credit where credit is due. Now I would say Korea is more open than Japan.

But I still sense that, to a great many Koreans’ frustration, Westerners still like Japan better. Why?

Korea doesn’t feel as exotic. When I talk about national branding, I say to Koreans: architecture, art, music, and food. The four things are very Korean. The music isn’t like Japanese music. The architecture has things in common with other countries, but the floors are unique. There’s old Korean culture that could be appealing to a Westerners, but when you drop in from the airport, you don’t see it.

As you’ve spent more time in Korea, what aspect of the country has come to seem most distinctly non-Western?

The spontaneity of things. People are very spontaneous in Korea, whether meeting friends or anything else. Westerners don’t do that. Japanese don’t do that. You don’t, when you’re a working adult, call your friend and say, “Let’s meet for a beer right now.” I wouldn’t do it in Ann Arbor. It’s related to how people interact with each other; that is where you get Koreanness, a sense of difference.

Seoul in 1983 (courtesy Robert Fouser)

Seoul in 1983 (courtesy Robert Fouser)

You wrote these books in Korean. How does your writing change when you write in that language?

Because Korean’s a foreign language, it’s a bit like a fog. I focus on, “Is my message clear?” It’s actually something to focus on when writing in your native language too. In your native language, sometimes you want to play with a sentence, make it more colorful. You start to think about style issues, and there’s the idea of being judged. “Do I have a good hook? Is it exciting? Does it hold together? Is there momentum? Do I have enough quotes?” With Korean, it’s “Does this make sense?” I focus on getting my message across, clearly, which is really what writers should focus on anyway. I lose track of that in English.

Why is Korean an interesting language?

I first studied Japanese, so when I studied Korean, I had that comparison. Later, the other interesting things were, from a linguistic point of view, speech levels, different ways of saying things, that kind of thing. The real difficulty for non-native speakers is knowing how to manage the speech levels, and within the speech levels knowing how to manage the verbal endings.

I’ve noticed people falling into a rut, using verbal endings without understanding their meanings. I had a Japanese student who thought the Korean ending -했는데요 meant the Japanese ending -ですが — which it does, but it doesn’t. She once left a note to me when she wanted to meet but I was a little late for the appointment and wrote “기다렸는데요” [literally, “I waited, but…”], a very antagonistic message to a professor which a Korean student would never write. But she thought it was polite.

The rules of grammar only do so much for you. That’s where you get the sociolinguistic issues. In linguistics, there’s thing thing called “markedness,” meaning using a non-neutral form, but every sentence in Korean is, in a sense, marked. There are no neutral sentences. In even in the most basic sentence — “This is a cup,” for example — I’m making decisions about who you are and who I am. That’s where a lot of non-native speakers end up in trouble.

Having acted as a linguistic intermediary between Korean and Japan while teaching the Korean language to Japanese university students, what’s something you learned about both cultures?

That was a great experience; I always got a buzz after class, which I didn’t get when I was teaching English. One group of students heard Korean was easy and just wanted to get the credits. Another group was the sort of “Korean wave” culture group, and another was interested in something else about Korea — it could’ve been anything. All the issues between Korea and Japan weren’t a big problem. Nobody was mad about Dokdo. They don’t hate each other. I found the Japanese students I taught very open and receptive.

What did you think as that “Korean wave” of pop music and television drama started to wash across Asia, considering your long history with the country?

I was pleasantly surprised. In a way, I thought it might happen. From 1996 to 2002 I wrote a weekly column for the Korea Herald where I would present different topics about Korea, especially the efforts Korea was making to recover from the I.M.F. Information technology was one positive, interesting story, and the other was this pop culture stuff. A lot of K-pop was very visual, and also free; that’s where the technology comes in. Americans or Japanese would have trouble with the idea of giving something out for free. It’s not a factor here so much. Korea almost foreshadowed the rise of the sharing economy.

What would you say to a foreigner looking for a way to live in Korea and experience it to its fullest? How to engage with Korea today, in a real way?

Always remember that the pace of change in Korea is so fast. Understand that the older generation has a very different experience than the younger generation. I went back to the house where I was born in Ann Arbor, and it’s not much different from the house I live in now: the fan heating system is the same, the thermometer is the same, the layout of the kitchen is the same. The paradigm of my life is physically the same as when I grew up. It’s not the same here.

Separate the institution you are working with from Korea itself. I found that out when I was at Seoul National University and not so happy there; some of the unhappiness was Seoul National, not Korea. Your workplace is your workplace, not Korea. Koreans hate institutions too. Try not to make that jump, which is where a lot of foreigners get into trouble. And learn the language.

In many ways, Korea is what you would expect from the geography: a place between China and Japan. How is it most different from those neighbors?

Korea is Latin — it has a Latin character, a Latin feeling, whereas China does not. That’s related to the spontaneity, and maybe to the popularity of the K-pop and dramas, where emotions are high. Japanese women watched [the 2002 hit Korean drama] Winter Sonata (겨울연가) because it reminded them of Japan years ago, when people were more emotional, had more of a sense of community, that sort of thing.

What message do you want to make sure Korea hears from you?

Democratization is a long process. It reached a crescendo in 1987, and after that concentrated on establishing local autonomy. The push extended to greater openness, more acceptance of people. That has nothing to do with foreigners; that was a Korean desire. Do not view that in the past tense. Your accomplishment should be viewed in the present tense. This is related now to openness not just to foreigners but to other kinds of Koreans, and later to reunification, if that happens. How will this society accept the former North Koreans? The push toward democracy is still going on.

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.