Nearly every day of the past few weeks, all the mobile phones in Seoul have gone off at the same time: some days once, some twice, some more than that. The cause is Korea’s emergency alert system, which in the years I’ve lived here has warned of flood risks, heat waves, and exceptional densities of air pollution. But now, in the time of the novel coronavirus or COVID-19, it announces each new outbreak, with details running to the area of the city in which it occurred. (Other regions of the country get announcements of their own.) The increased frequency of these simultaneous rings and vibrations colors life in Seoul these days, as do the thousands of surgical-masked faces seen in the street, the Mandarin-speakers wearing “I AM FROM TAIWAN” buttons, and the subway-station announcements — repeated over and over again in various languages including an especially loud English — about the importance of thorough hand-washing.

Though I can hardly complain about the greatly increased ease of getting a seat on the subway, nobody can ignore how much more subdued life in Seoul has become, and how quickly. But Seoulites can at least take comfort in the fact that they’re not in Daegu, the city roughly 150 miles to the southeast where the coronavirus made its dramatic Korean debut. (It now seems members of Daegu’s Shincheonji Church of Jesus, one the many religious sects thriving in this country, carried the virus back after a visit to a branch in Wuhan, the Chinese city from which it originated.) Last week I asked an acquaintance from Daegu, who had to make a trip to his hometown for dental work, what the city looks like nowadays: he compared it to I Am Legend, the movie about the aftermath of a virus that kills off 90 percent of humanity.

Fans of Los Angeles cinema may be more familiar with an earlier telling of the same story: 1971’s The Omega Man, which stars Charlton Heston as the last man alive in the city — apart, that is, from a group of nocturnal albino mutants. Both films are based on Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel I Am Legend, one of the works of literature to which the coronavirus promises a renewed readership. The wide spread of the virus means this now obtains not just in Asia but in the West, in whose oldest major pandemic novel A Journal of the Plague Year Daniel Defoe fictionalizes the diary of a survivor of the Black Death that swept through London in 1665. Though remembered as a European disease, the bubonic plague left its mark elsewhere, sometimes repeatedly: Oran, the second-largest city in Algeria, lost much of its population to the disease in 1556 and 1678, with three smaller-scale outbreaks in the 20th century.

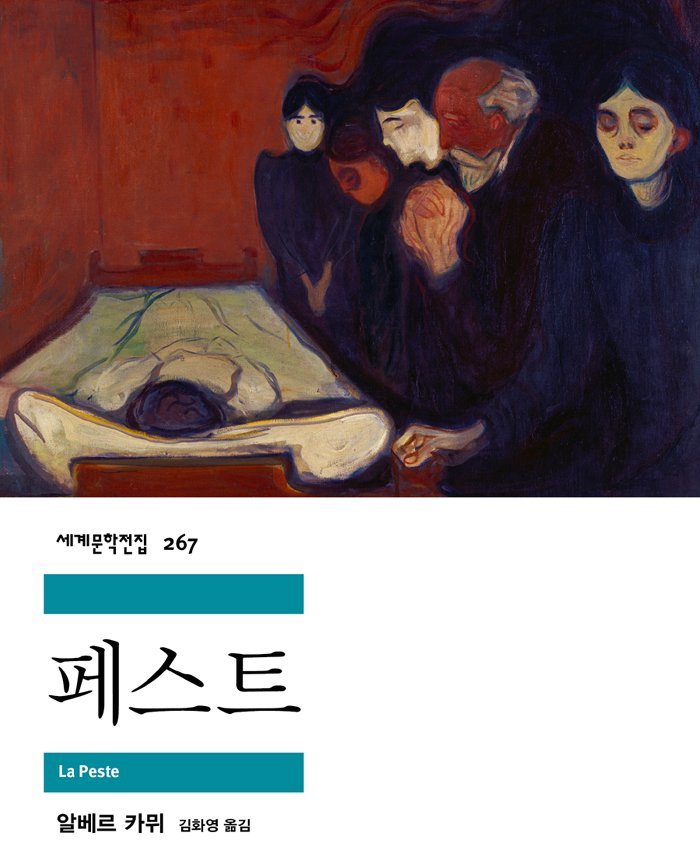

If we associate the plague with Oran, we do it not because of historical fact but because of a fiction: Albert Camus’s The Plague (La Peste). Originally published in 1947, it tells of a seemingly contemporary outbreak of the bubonic plague that forces the city to close its gates for the better part of a year. Causing hundreds of deaths per day at its height, the plague the Algerian-born Camus invents far exceeds in magnitude the then-recent epidemics visited upon the real Oran. Perhaps that extremity itself has ensured the novel’s popularity whenever and wherever modern disease threats have loomed: no matter what, readers can take comfort in the assumption that things won’t get as dire as they do in the book. But the current coronavirus is novel in more ways than one: nowhere in the world do we really know how far it will spread, how long it will last, or how competently authorities will deal with it. Italy and France now have the most coronavirus cases in Europe, and sales figures reveal that readers in both countries are turning to the reluctant existentialist for perspective.

Reading The Plague here in South Korea, the second-most coronavirus-afflicted country in the world, one instinctively spots parallels between art and life. “The town itself, let us admit, is ugly,” writes Camus (in translation by Stuart Gilbert), describing Oran in a way more than a few have described Seoul, let alone the even more utilitarian likes of Daegu. Its citizens “work hard, but solely with the object of getting rich,” and one character, an outsider, writes of his fascination with “the commercial character of the town, whose aspect, activities, and even pleasures all seemed to be dictated by considerations of business.” The people of Oran, writes Camus, “were like everybody else, wrapped up in themselves; in other words they were humanists: they disbelieved in pestilences. A pestilence isn’t a thing made to man’s measure; therefore we tell ourselves that pestilence is a mere bogy of the mind, a bad dream that will pass away. But it doesn’t always pass away and, from one bad dream to another, it is men who pass away, and the humanists first of all, because they haven’t taken their precautions.”

A chilling thought, but for humanists or anyone else, precautions aren’t particularly hard to take in Korea, thanks to everything from the suddenly omnipresent (if often installed in a makeshift manner) hand-sanitizer dispensers to drive-through coronavirus testing stations. That those surgical masks do little to prevent the general transmission of the virus even if correctly used has by now been well publicized, not that it’s slowed the demand for them. As a result they’ve become somewhat difficult to acquire and subject to purchasing restrictions, just as in Camus’s Oran “peppermint lozenges had vanished from the drugstores, because there was a popular belief that when sucking them you were proof against contagion.” The Plague illustrates what happens when a closed-off city loses the ability to replenish its stocks of lozenges or anything else, at least through legal channels. But the grinding shortages described by Camus remind me less of anything I’ve experienced in Seoul than of the news of empty shelves and deserted ports coming out of the much less afflicted United States.

Judging by the absolute number of coronavirus cases, the situation in Korea looks bad indeed. But the methods of diagnosis and treatment here have drawn praise in a way that those in place in the United States have not, to put it mildly. (“Chaos at Hospitals Due to Shortage of Coronavirus Tests,” announces one Los Angeles Times headline.) The same holds for the behavior of the public: “toilet-paper panic,” for instance, remains unknown in Korea. Still, talk of the coronavirus has become inescapable in Korean media, news and otherwise, and recently that talk has taken on a critical edge against President Moon Jae-in. Despite having campaigned in part on the promise of more effective disaster preparedness — in contrast to his now-jailed predecessor Park Geun-hye, in office when the MV Sewol sank — Moon declined to ban entry from China when it could have prevented the virus’s spread into Korea. Things might have gone differently had the original outbreak happened in, say, Japan, but as it is the official responses (or lack thereof) to the coronavirus cast a harsh light on the extent of Korea and the world’s fears of alienating China.

Camus, too, writes of such a sharp turn of public sentiment. Not long after plague-infected rats begin turning up dead in the streets of Oran, “there was a demand for drastic measures” and “the authorities were accused of slackness.” Soon the press mounts a “campaign against the local authorities”: “Are our city fathers aware that the decaying bodies of these rodents constitute a grave danger to the population?” Unlike the bubonic plague, which for centuries threatened to “rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city,” the coronavirus is brought to every place in which it spreads by human beings. But whoever or whatever transmits it, governments everywhere have long shown a fatal hesitation to call an epidemic an epidemic. “I was in China for a good part of my career, and I saw some cases in Paris twenty years ago,” The Plague‘s doctor protagonist Bernard Rieux hears from an older colleague. “Only no one dared to call them by their name on that occasion. The usual taboo, of course; the public mustn’t be alarmed, that wouldn’t do at all.”

And indeed, it is in China that this phenomenon has most visibly repeated itself. Early in the novel the wary chairman of the Oran Medical Association admits that “if the epidemic did not cease spontaneously, it would be necessary to apply the rigorous prophylactic measures laid down in the Code. And, to do this, it would be necessary to admit officially that plague had broken out. But of this there was no absolute certainty; therefore any hasty action was to be deprecated.” This parallels the story of the coronavirus’s early spread: the Chinese government, too, dragged its feet taking action, and before acknowledging the virus’s existence even admonished the first doctors to discuss it as “rumormongers.” Such crises tend to have to reach a certain pitch before their existence is officially admitted: in Camus’s Oran, only when the daily death roll reaches thirty does the telegrammed order come down to proclaim a state of plague and lock down the city. “So they’ve got alarmed at last,” says Oran’s Prefect.

Camus dramatizes the variety of responses to prolonged isolation and rampant disease, two conditions not unknown in human history. But his concerns go beyond the literal: as J.M. Coetzee puts it, “The Plague also invites a reading as being about what the French called ‘the brown plague’ of the German occupation, and more generally as about the ease with which a community can be infected by a bacillus-like ideology.” The coronavirus has already provoked no few ideological or at least political reactions: in Korea it has become a byword for spinelessness toward China, as well as an indictment of organizations like Sincheonji. Unsurprisingly, the American press has come up with takes framing the epidemic as a biological correlative of anti-Asian prejudice. All this against the background noise of predictions about the coronavirus’s ultimate duration and deadliness, some “based on far-fetched arithmetical calculations, involving the figures of the year, the total of deaths, and the number of months the plague had so far lasted,” and others whose “apocalyptic jargon” announces “sequences of events, any one of which might be construed as applicable to the present state of affairs” and “abstruse enough to admit of almost any interpretation.”

Thus far, the coronavirus in Korea has offered little gruesome enough to compare with Camus’s plague: the exploding buboes, the agonized death throes issuing onto the streets, the mass graves hastily filled and covered over. “Formalities had been whittled down, and, generally speaking, all elaborate ceremonial suppressed,” Camus writes as the situation in Oran worsens. “The plague victim died away from his family and the customary vigil beside the dead body was forbidden, with the result that a person dying in the evening spent the night alone, and those who died in the daytime were promptly buried.” But even this is reminiscent of what’s happening in Korea: the fellow from Daegu mentioned an elderly relative rushed to cremation immediately after dying of the coronavirus. He told me this in a crowded café, the likes of which Rieux visits in Oran out of a “need for friendly contacts, human warmth.” Though public facilities like libraries and community centers have shut their doors for the time being and schools have pushed back the start of spring semester, most of Seoul seems to be doing business nearly as usual.

My own impression may skew slightly positive, living as I do in a part of town with a hard core of students out and about day and night (especially when they don’t have lectures to attend). I myself take it as something of a civic duty to continue patronizing all my favorite spots, given how many of the ones I used to frequent went under even in times without epidemics. But those who choose to stay home benefit from Korea’s highly developed food-delivery infrastructure (though custom now dictates asking the deliver to leave one’s meal outside the door instead of ringing the bell) as well as the products of its robust entertainment industry. Video-on-demand services have brought back out Kim Sung-su’s Flu (감기), a 2013 film the outbreak of an especially deadly strain of the of H5N1 virus in the suburbs of Seoul; this coming week will see the second-season premiere of Kingdom (킹덤), a Netflix series about a mysterious plague in the late 16th century. No matter their setting, these and other recent plague tales all owe something to Camus’s novel, whose balance of specificity and generality, as well as of storytelling and philosophy, elevates it to the level of myth.

The coronavirus’s spread will continue, and like the townspeople of The Plague, all of us around the world will continue to speculate futilely about it. We may also find occasion to reflect upon the aptness of the term “viral,” as in current expressions — unimaginable in Camus’s day — like “going viral.” That usage applies to fast-spreading internet trends, and South Korea may famously be one of the most “wired” countries on Earth, but what struck me when I first visited was the speed of its offline trends. One day I’d see the same T-shirt with a bejeweled-eyed owl, say, on two or three people, and the next day I’d see it everywhere. Designer surgical masks have only just begun to emerge, but this doesn’t just happen with clothes: “fire chicken” was the comestible of the moment back then, a status now apparently held by brown-sugar drinks. A few years ago, versions of the British Blitz-era “Keep Calm and Carry On” poster began appearing in the bookstores and coffee shops of Seoul, most of them evidencing little understanding of its original contexts. Like most fads here, Korean “Keep Calm…” posters vanished almost as soon as they appeared, but surely there’s never been a more appropriate time for them to come back. Then again, few Seoulites seem to need the advice.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Los Angeles and Seoul, a Tale of Two Ugly Cities

America Has School Shootings, Korea Has Sinking Ships

Reading Tocqueville in Korea (Part One)

Reading Tocqueville in Korea (Part Two)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.