“Culture is not necessarily our destiny,” wrote the high-profile Korean activist and later president of South Korea Kim Dae-jung in a 1994 Foreign Affairs piece. “Democracy is.” Kim made that claim as part of an argument against Lee Kuan Yew, three-decade prime minister of Singapore, who took a dim view of transplanting Western political institutions into Asian soil. Like many pronouncements heard in Korean public life, Kim’s framing of democracy as destiny possesses in forcefulness what it lacks in understandability: not that I’ve read all or even most of Kim’s voluminous writings, but try as I might I’ve never been able to understand quite how he arrived at so unambiguous a conclusion. I keep thinking of the student protesters P.J. O’Rourke interviewed in the 1980s: “What’s this election all about?” “Democracy.” “But what is democracy?” “Good.” “Yes, of course, but why exactly?” “Is more democratic that way!”

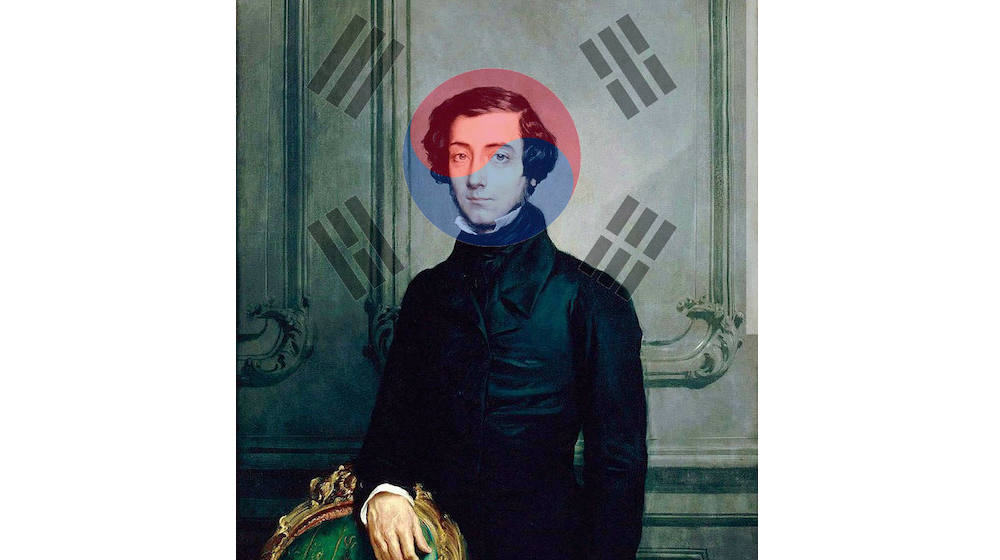

But democracy has been compelling as a subject of discussion since the invention of the thing itself, and before the world began to watch in fascination as democratic (or at least quasi-democratic) institutions spread across Asia, it watched in fascination as they took shape in that grand experiment known as the United States of America. Of all the copious observations made on democracy in America, none have proven more enduring than Democracy in America, the French diplomat, political scientist, and historian Alexis de Tocqueville’s first-person study of that new country, its laws, and its customs first published in two parts in 1835 and 1840. “Everyone can see that a widespread revolution toward democracy is in full swing amongst us,” Tocqueville writes early in the first volume. “Some look upon it as something new and, taking it as an accident, are still hoping to be able to check its progress, whereas others” — the Kim Dae-jungs of the world — “consider it irresistible because they see it as the most sustained, longstanding, and permanent development ever found in history.”

As I’d hoped when I first moved to Korea, living outside my native America has made me not just that much more interested in but that much more observant the quality of American life whenever I make a trip back (one of which I’m on even as I write this). I’ve long agreed with those who still rank Tocqueville among the most perceptive observers of the United States even 180 years on, and reading through Democracy in America again, now at a great distance from the country itself, has only strengthened that agreement. But I’ve found that Tocqueville also has much to say, at least indirectly, about Korea: his reflections on the workings of a 50-year-old democracy can hardly fail to resonate when read in a 30-year-old democracy, let alone one that, much like mid-19th-century America, has undergone an previously unimaginable amount of development in just a few decades — and in a moment when much of the world has stopped to consider how much of a future liberal democracy as we know it really has.

Much like Percival Lowell describing Korea in the 1880s, Tocqueville begins with the geography of the United States of America, which at that time hadn’t expanded all the way across the continent: its 24 states “and the three great districts not yet included in the ranks of the states” were home to just 12 or 13 million people. Though he does celebrate the country’s vastness, its abundance of natural resources, and its even isolation (of the Americans “it might almost be said that no one needs them and they need no one”), he doesn’t take long to get to where his main interest lies, and indeed where one could argue that, in the truest sense, America itself lies: the law. “There is no country in the world where the law has a more absolute voice than in America,” he writes, “nor where the right of applying it is shared among so many hands.”

This in contrast to what I heard just last week from a woman who emigrated from Korea to Canada years ago: “There is no law in Korea.” Come off though that may as an immigrant’s reflexive trashing of the land they’ve left behind, it does align somewhat with my own observations of the fundamental differences between Korea and America. I might place the emphasis differently: it’s less that Korea has no law than that Korea doesn’t have the West’s, and especially America’s, obsession with the law. The Korean reluctance to solve problems using the law — a last recourse, it seems, only when all more informal societal tools have failed — throws into stark contrast the American instinct to reach for the law in every situation, even among neighbors and family. “Americans almost always carry the habits of public life over into their private lives,” Tocqueville writes. “With them, the idea of a jury surfaces in playground games and parliamentary rituals are observed even in the organization of a banquet.”

But even when examining America through its laws, Tocqueville sees a picture of society “overlaid with a democratic patina beneath which we see from time to time the former colors of the aristocracy showing through.” This sounds like the lament, often heard in educated circles, that for all the development that has rocketed Korea into the first world, it never fully shook off the attitudes built up over centuries and centuries in a peasant society overseen by near-idle aristocrats. Ask a Korean to identify their country’s ruling class in the 21st century, and they’ll most likely point to the families that own the chaebol, the industrial conglomerates like Samsung, Hyundai, and LG that rose after the Korean war along with the country itself and now wield more power — and indeed command more respect — than the government. “If you ask me where American aristocracy is found,” Tocqueville writes, “my reply would be that it would not be among the wealthy who have no common link uniting them. American aristocracy is found at the bar and on the bench.”

This, to Tocqueville’s mind, is no bad thing, as “the power given to lawyers and the influence permitted to them in government today form the most potent barrier against the excesses of democracy.” The question of how much rule by the people is too much rule by the people has long been hotly debated in this branch of political philosophy, and Tocqueville’s homeland provides him with a richly contrasting example to work with in approaching it. “In the exercise of executive power the President of the United States is constantly subject to a jealous scrutiny,” he writes, whereas “the king of France is absolute master in the realm of executive power. The President of the United States is responsible for his actions. French law declares the person of the king inviolable.” But “above both hovers a commanding power, namely, public opinion.” In America “it works through elections and decrees; in France, through revolutions. France and the United States have thus, despite the differences in their constitutions, this shared feature: that public opinion ends up being the commanding power.”

If the United States and France alike are ultimately governed by public opinion, then Korea, as Michael Breen wrote in Foreign Policy at the time of the protest-driven impeachment of Korean president Park Geun-hye, is ultimately governed by public sentiment. “This is as tame an expression in Korean as it is in English and does not convey the underlying phenomenon,” Breen writes. “A more accurate phrase would be ‘the emotion of the masses’ or ‘mob passion.’ But these have negative connotations, and public sentiment for Koreans is anything but negative. It is the collective soul, and it is considered supreme.” Kim Dae-jung had an even more characteristically unambiguous way of putting it: “The people are God.” Public sentiment rose up against Park and stopped her from completing even one term as president — though one term is all the president of South Korea gets even in the best of times, a condition of which Tocqueville would likely have approved.

“Have the legislators of the United States been wrong or right to allow the re-election of the president?” Tocqueville asks in Democracy in America‘s first volume. “Intrigue and corruption are natural weaknesses of elective governments. But when the head of state can be re-elected, these weaknesses stretch out endlessly and threaten the very existence of the country.” It is impossible, he writes “to observe the normal course of affairs in the United States without realizing that the wish to be re-elected dominates the president’s thoughts and that all the policies of his administration are geared to this objective.” Were the president ineligible for re-election, “he would not be independent of the people for he is still responsible to them; but the support of the people would not be so necessary as to force him to bend to their will in everything,” to become “but a docile tool in the hands of the majority.” But then, it takes only a glance at the fates of many of the past presidents of South Korea — disrepute, imprisonment, suicide — to understand that a single five-year term hardly assures a healthy relationship with the public.

Having dealt with public opinion, Tocqueville gets into the differences between large and small countries, an even more relevant question when comparing America at its current size to South Korea (with its land area one-quarter of California’s) than when comparing the America of the 1830s to France. He might almost be describing Korea when he writes that “among small nations, the eye of society sees everywhere,” that “the spirit of improvement reaches the smallest details,” that “national ambition is much affected by weakness,” and that “the efforts and the resources of the people turn almost entirely toward their inner prosperity.” Koreans who remember the 18-year rule of Park Geun-hye’s father Park Chung-hee, and even more so that of his military successor Chun Doo-hwan, may know just what Tocqueville means when he writes that “when tyranny takes root in a small nation, it is more awkward than anywhere else because its influence spreads to everything within a circle which is much smaller in extent,” that it “displays both a violent and fretful character,” and that it “abandons the political domain which is properly its own to meddle in people’s private lives.”

Can any American fathom what it is to live in a small country, and thus know what it is to live in a large country, unless they try it themselves? The smallness of a country like Korea can be the source certain discomforts on an American living there, but it can also be the source of many more comforts. “If there were only small nations and no large ones, humanity would quite certainly be more happy and free,” Tocqueville writes, “but large nations cannot be avoided.” And for those small nations — even Korea, for so long a “Hermit Kingdom” — relations with those large nations cannot be avoided. “What good are its industries and trade, if another nation rules the seas and lays down the law in all the markets?” asks Tocqueville. “Small nations are often wretched, not from their size but because they are weak; large nations prosper, not because of their size but because they are strong.” And so “small nations always end up by being united to great nations either by force or by joining voluntarily,” an observation demonstrated over and over again in Korea’s history with China, Japan, and now the United States of America.

“I know of nothing more pathetic,” Tocqueville writes, “than the sight of a nation which can neither defend itself nor provide for itself.” While a country as industrially productive and military robust (to the point of conscription, an idea that strikes Tocqueville as “so alien to the ideas and so foreign to the customs of the people of the United States that I doubt whether they would ever dare to introduce it into their law”) as South Korea doesn’t quite fit that description, it does provide a steady stream of abjectly imitative attitudes and behaviors toward richer nations, especially those of the West. (I suspect I’ve already commented on its not especially fruitful fixation on the English language enough here.) This combines with the widespread ascription of every complaint in life, no matter how universal or trivial, to some deeper defect in the culture of Korea itself, a tendency almost never seen in the United States, where hating one’s job, one’s school, or one’s apartment building doesn’t naturally lead to hating America.

But perhaps Korean history explains some of this, and in a way Tocqueville would have understood. “Sometimes in the life of nations there occurs a moment when ancient customs are changed, behavior patterns destroyed, beliefs upturned, the value of memories has vanished and where, nonetheless, education has remained in an imperfect state and political rights are ill-founded and restricted,” he writes, describing the kind of moment visited on Korea more than once. “At such a time, men no longer perceive their native land except in a feeble and ambiguous light; their patriotism is centered neither on the land which they see as just inanimate earth nor on the customs of their ancestors which they have been taught to view as a yoke, nor on religion which they doubt, nor on laws which they do not enact, nor on the legislator whom they fear and despise. So, they can no longer see their country portrayed either under its own or borrowed features and men retreat into a narrow and unenlightened egoism. These men escape from prejudices without recognizing the power of reason; they have neither the instinctive patriotism of a monarchy nor the reflective patriotism of a republic; but they have come to a halt between the two in the midst of confusion and wretchedness.”

Does 21st-century Korea find itself in the midst of that same confusion and wretchedness? I do sometimes feel like shouting at the country to just be itself, but on another level I realize that it may not know what itself is much better than any does the average Westerner passing through. Or at least it doesn’t know how to conceive of itself without reference to other, bigger, more thoroughly proud countries. “For 50 years the inhabitants of the United States have been repeatedly told that they form the only religious, enlightened, and free nation,” Tocqueville writes toward the end of Democracy in America‘s first volume. “They see that the democratic institutions of their country are prospering whereas they are failing in the rest of the world. They possess, therefore, an inordinate opinion of themselves and are not far from believing that they form a species apart from the rest of humanity.” What frustration I have with Korea comes not from the fact that I hold those opinions about America, but that Koreans do.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Korean Cinema Looks Back at 1987, When Students Died and Democracy Was Born

Anti-Trump Protests, Anti-Park Protests, and the Koreanization of American Politics

The Adventures of Percival Lowell, Famed Astronomer and Early Writer on Korea

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.