By Colin Marshall

Like many a Westerner with an interest in Korea (and without any stake in the relevant historical conflicts), I’ve also cultivated a parallel interest in Japan, and I find few things Japanese as interesting as I find Japanese architecture. Who, I began to wonder as I learned more about the architecture of Japan and the culture of Korea, stands as the Korean equal of a Kenzo Tange, a Kisho Kurokawa, or a Tadao Ando, with their deep concerns not just for the aesthetics but the shape of society to come? I didn’t have an answer until, on a walk through central Seoul with scholar of the both the Korean language and built environment Robert Fouser (whom I more recently interviewed here on the Korea Blog), I first visited Seun Sangga, South Korea’s first large-scale residential-commercial complex.

Built in 1966 during the mayoral term of Kim Hyon-ok, nicknamed “the Bulldozer,” the kilometer-long linear development, which stretches across blocks and blocks of downtown Seoul, didn’t take long to draw disdain as a “concrete monstrosity” (or the Korean-language equivalent thereof). “The phrase reverberates,” says defender of British brutalism Jonathan Meades in his documentary Concrete Poetry of that now-standard architectural slur. “Any modest, self-effacing newspaper columnist can be sure that he will please readers with the same ready-made formula. For, as we all know, concrete monstrosities are culpable of virtually everything: they promote every known social ill, and many which have yet to be revealed.”

Though it does contain plenty of concrete, Seun Sangga is, of course, not British, nor is it exactly a work of brutalism. We could, perhaps, call it a work of pure developmentalism, erected as both a symbol of and a contribution to to the country’s fast-growing postwar economy: in addition to the massive amount of retail space on the lower floors, this “city within a city” had first-class apartments (at least by the standards of Korea in the 1960s) on the upper and even boasting such then-unheard-of amenities as a fitness center. It nevertheless fell so far short of its even more ambitions original design, which included glass atria and a transportation system to connect all the buildings together, that the complex’s architect disavowed it.

That architect turns out to have been Kim Swoo-geun (김수근) , the most famous Korean of his profession in the twentieth century. In addition to designing a number of other notable, non-disavowed structures in his homeland and elsewhere under the banner of his Space Group of Korea, he also launched SPACE, the country’s first arts and architecture magazine, which this year, despite the 2014 bankruptcy of the Space Group, celebrated a half-century in print, surviving Kim himself by thirty years. Rejecting “purely Western models on the one hand and extreme nationalism or patriotism on the other,” as the Kim Swoo-geun Foundation puts it, he “developed his original concept of architecture that synthesized the changing conditions of postwar Korea with the widely forgotten Korean cultural history and primordial spirit.”

“During the 25 years Kim Swoo-geun was active as an architect in Korea, its state-driven monopolistic economy grew at an average rate of ten percent,” writes University of Seoul professor Pai Hyung-min in SPACE. “His career began in a country that was one of the poorest in the world and ended amidst its preparations for the Olympics. It spanned a period of three different dictatorial regimes, and sadly, he never lived to see a Korean democracy take hold.” A man ahead of his time in more ways than one, he also had to deal with a certain sensibility gap between himself and his country as “a highly disciplined and refined architect in a society that viewed architecture mostly as a technical attachment to construction,” caring little about the charges of architectural deficiency that would result.

Kim had much in common another Korean who became famous in the 1960s and 70s: the video artist Nam June Paik. The two actually spent some time together as classmates at the esteemed Kyunggi Public Middle School a few years before their respective escapes from Korea at the outbreak of the Korean War. Both ended up in Japan for their higher educations, Paik studying music at the University of Tokyo and Kim studying architecture at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, and both married Japanese wives. But while Paik, fearful of punishment for draft-dodging, remained in exile until the 1980s, Kim returned to Korea in 1960 and to find favor with the aggressively modernization-minded government of Park Chung-hee.

The concrete Seun Sangga has spent much of its life unloved, and not just by Kim himself; critics have long regarded the ivy-covered brick Space Group Building (공간 사옥), built in 1971 in a more deliberately historic quarter of Seoul, as his masterpiece. Not only does it exemplify the sort of irregular, organic aesthetic Kim pursued after turning his back on mega-projects, it’s proven amenable to additions and revisions over the intervening decades: the Space Group’s own Chang Sea-yang put on a glass-walled wing in 1997 (which contains a nice cafe, though I much prefer the old-fashioned coffee shop that has operated for decades almost without change in Seun Sangga), and his colleague Lee Sang-leem rebuilt and enlarged the traditional Korean courtyard house at its center (also with its own cafe) three years later.

After the Space Group’s bankruptcy, the building’s purchasers turned it into a modern art gallery called the Arario Museum, making use of Kim’s philosophically thought-through and quite unusual use of interior structure (as well as showcasing work by, yes, Nam June Paik). Though it may have faced an uncertain future for a little while there, the Space Group Building has never faced an imminent threat to existence. Seun Sangga, by contrast, had its days numbered in 2009, when the accepted plans dictated a complete knockdown and rebuild — a project born of the very same kind of impulse that created Seun Sangga it in the first place. But half a decade later, with only one of its buildings destroyed, political and public sentiment had changed enough — and economic growth had slowed enough — to stay the wrecking ball.

The dream, as now evidenced by notices posted in subway trains and speculative plans displayed at the recent Seoul Architecture Festival, has turned from replacement to revitalization. Which isn’t to say that Seun Sangga lacks vitality in its current state, its countless corridors lined with electronics dealers who still seem to do reasonably well for themselves selling everything from stereos to security cameras to sewing machines. (Generations of Koreans remember paying a visit to buy their first turntable or personal computer.) That also goes for the restaurants and print shops and all the other sorts of businesses that even a frequent Seun Sangga-goer such as myself has yet to discover. But those with an interest in not just the complex and its predominantly low-rise, industrial surrounding areas but Seoul’s urban future itself now use it as the starting point for the question, “What next?”

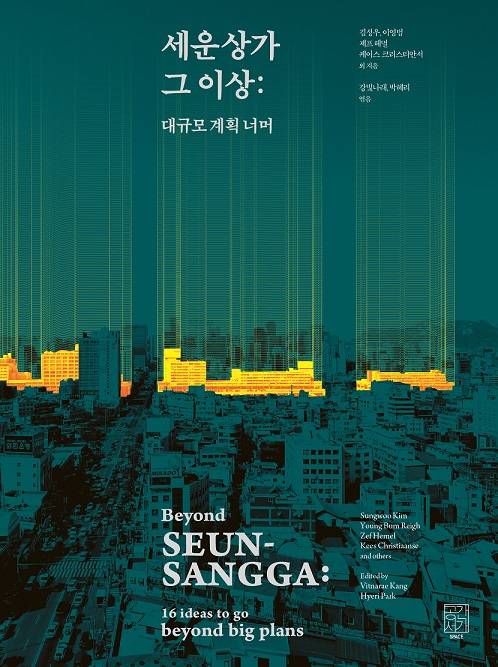

This year, SPACE‘s book-publishing arm put out a collected variety of answers to that question in the form of Beyond Seun Sangga: 16 Ideas to Go Beyond Big Plans. This bilingual book contains sixteen proposals, contributed by architects and researchers based in both Asia and Europe, for what do do with, or at least how to think about, what Kyonggi University professor Reigh Young Bum calls this aging “urban symbol of the modern growth machine.” Most of the essays look to examples, in Korea and abroad, of the revitalization of dilapidated urban developments — Rotterdam and Berlin come up a few times each — through local, small-scale, low-risk, and decidedly non-big-ticket efforts to improve the quantity and quality of public spaces.

Seoul has one of the most celebrated public spaces of the 21st century in the Cheonggyecheon, a stream that happens to run right through Seun Sangga. (That coffee shop I like lucked into a view of it.) It famously replaced a utilitarian elevated freeway overpass built in the 1970s, not long after Seun Sangga, and opened for strollers, picnickers, buskers, tourists, and many other besides in 2005, beginning a new era characterized by urban projects as least ostensibly conceived to make the city more pleasant. The buildings of Seun Sangga, each of which has a wraparound elevated deck owned by the City of Seoul, have started to display a similar kind of public-space potential as places where disparate generations, professions, and lifestyles can converge.

The low rents, as several of Beyond Seun Sangga‘s authors point out, also help. Bookstores and galleries, as well as whimsical murals painted over storefronts temporarily or permanently shuttered, have only just begun to appear. I recently attended an audio-and-video festival held across three of its buildings, using the occasion to ask around about whether any of their apartments remained available to rent in case the lease on my current apartment proved unrenewable. Whatever its potential inconveniences, the prospect of living in one of the very places where what sort of city Seoul will become is even now being imagined — and not just imagined, but tried out — certainly appeals. Whatever happens there, the future of the city looks more organic and improvisational than it has in about a century. Seoul, in other words, has finally started to catch up with Kim Swoo-geun.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Walking Deep Into Seoul with an Expert on the Korean Built Environment

Living the Vertical Life in Seoul

Learning from the Korean City

A Society of Screens: the Korea, and the World, Envisioned by Nam June Paik

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.