Even though I live there, I still only with difficulty perceive Northeast Asia through any lens not borrowed from Chris Marker. This owes mostly to the influence of dozens of viewings of Sans Soleil, his 1983 fact-and-fiction cinematic travelogue through places like Iceland, Cape Verde, San Francisco, and especially Japan, a feature-length realization of the peripatetic form of “essay film” he invented with 1955’s Sunday in Peking. Between that and Sans Soleil, he’d gone to Tokyo during the 1964 Olympics and come back with the materials for a 45-minute documentary about the titular young woman whom he happened to meet in the street there. Le Mystère Koumiko came out in 1965, just three years after his best-known work: La Jetée, the short drama of apocalypse, time travel, and memory made almost entirely out of still photographs.

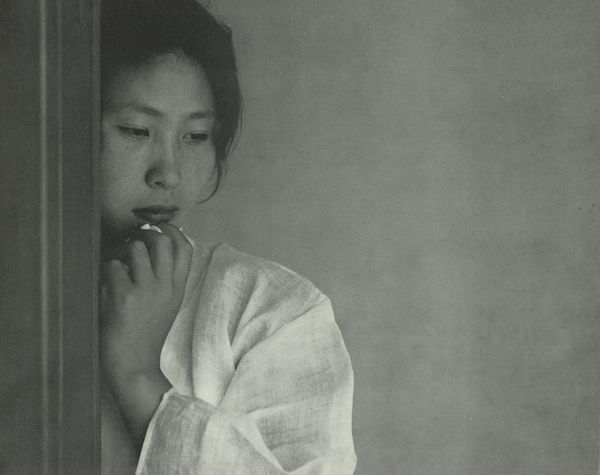

But Marker also made it, camera in hand, to the Korean Peninsula as well — and the northern half of the Korean Peninsula at that. He’d accepted an invitation in 1957 to join a delegation of French journalists and intellectuals including Claude Lanzmann, Armand Gatti, and Jean-Claude Bonnardot: Lanzmann, so the legend has it, fell in with a nurse there. Gatti and Bonnardot, more productively, made the feature film, the first and only North Korean-French co-production, Moranbong (not to be confused with the North Korean girl group of the same name). Marker took the pictures that would, in 1962, appear as the photobook Coréennes, titled with the feminine form of the French noun meaning “Koreans.” It brings to mind — or at least brings to my mind — Marker’s quotable quote: “In another time I guess I would have been content with filming girls and cats. But you don’t choose your time.”

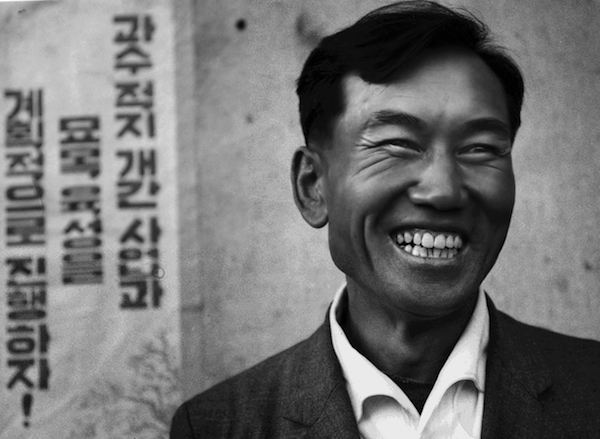

Had Marker’s time been the 19th century of travelers like Percival Lowell, he would have enjoyed nary a glimpse of Korea’s hidden-away womankind, let alone its strictly hidden-away young womankind, but this “prototype of the twenty-first-century man” (in the words of collaborator Alain Resnais) paid his visit in the middle of the twentieth. While he could and did photograph plenty of girls (though, apart from historical representations of Korea’s much-mythologized tiger, no cats), he also captured the images of a host of other North Korean citizens besides: children, scholars, soldiers, vendors, pranksters. The title of Coréennes‘ Korean edition, 북녘사람들 or “Northern People,” thus more accurately reflects the content of the book, although its English-language edition stuck, as many of the English-language releases of Marker’s movies have, with the original French one.

Unlike in France or South Korea, the book has in the Anglosphere long since gone out of print, but the fan site markertext.com has preserved its words (and offers a Korean translation of San Soleil‘s script besides). Marker interweaves historical accounts of European encounters with Korea with that of his own, writing of a young woman who spontaneously “told us her life story” (or “more precisely, she explained to us that there was nothing to be told”); the zealous young cadre at a chemical plant who weeps at the unexpected mention of her parents, killed in the war, immediately prior to launching into an “extraordinary hymn of hate and willpower”; the marketplace, or “Republic of things (I mean the ideal Republic, of course),” where “baskets, earthenware jars, bundles of wood, basins, all escape the earth’s gravity to become satellites” balanced on the heads of their bearers, where “Jesuit chastity and Marxist austerity agree to underscore other medical properties of ginseng,” and where “six children watched me watching them” in “a mirror game that goes on and on.”

Marker expresses little but admiration for North Korean society and the people in it. “I wish that my country should truly be worthy of being called the most polite in the world,” he quotes Jean Giraudoux as saying, “which is to say, that its men and women should be beautiful.” This prompts Marker to declare that “along with China, Italy, and Bororo land, Korea” — here as everywhere in the text, he uses the northern half of the peninsula to stand for what common culture spreads across the whole — “is worthy of being called the politest country in the world.” He praises the ingenuity and industry in the face of poverty, and in a country badly in need of reconstruction, that guarantees that “when there aren’t any cranes, they invent them – in sections. When there aren’t any trucks, out come the wheelbarrows, the hods, the boats, the cupped hands, the Marne taxis.” In North Korean factories, “hardly has the break-whistle sounded” than the workers have sprung at the sound of the changgo drum (which “makes even tigers dance”) back to the job at hand, “as though they could only rest from one effort with another, as though they somewhere had an hourglass that need only be upturned for all that accumulated, inert fatigue to become energy again.”

But what of the problems, to put it mildly, of North Korea’s political situation? Did its combination of quaintness and Utopian promise blind the instinctively left-leaning Marker, who would soon make make films like Cuba Si!, to the prospect of totalitarian abuses to come? “Framed closely in black and white, the Bearded Ones looked wedded to authenticity,” writes Clive James in his book Cultural Amnesia on Marker’s essay-film on Castro’s revolution, which gave him the reputation among “foreign observers as being by far the best mind of the movement that became internationally famous as the nouvelle vague. Admittedly the competition wasn’t strong,” though at least, unlike his descendants in political documentary like Michael Moore, who when he says “that the poor of the world could have clean water overnight if the advanced nations agreed to it, must know that he is talking nonsense,” Marker “really did believe that there was a collectivist answer to the troubles of the world.”

But Coréennes‘ lack of engagement with the ideological aspect of North Korea comes less out of delusion than deliberate omission. “I will not deal with the Big Issues,” Marker says in a letter to his cat at the book’s end. “Were I to speak of them, it would be in the style of Henry V: ‘An orator is only a loud-mouth, a motto is only a slogan, politics change, statistics are faked, fine alliances break, bright flags tarnish, but a human face, good cat, is the sun and the moon…’” A coda, composed at a considerable temporal distance, follows: “Those men and women whom I saw work so hard, with a courage the propaganda-makers didn’t hesitate to exploit, but which it would be stupid to confuse with its imagery – did they really work for nothing? The newspapers one reads in spring 1997 are devastating: ‘famine,’ ‘total failure,’ ‘corruption everywhere’… There’s no reason to beat around the bush: that wager was lost, terribly, and the Koreans have once again illustrated their Greek propensity for hubris. Always excess, in sentiment, in war, in history.”

Seldom has any observer, foreign or local, expressed the Korean condition, North or South, so succinctly. But then, few have enjoyed the degree of unfettered human interaction North Korea granted to Marker and his cohort, especially not the tour-package cellphone shutterbugs who labor under the constant, sweaty attention of their state-issued minders today. “The four years following the war (a conflict soberly described by General Bradley as the ‘wrong war, in the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy’) had been dedicated mostly to rebuilding a bomb-stricken country, and the formidable propaganda machine that would soon be identified with the sheer mention of North Korea wasn’t yet running at full throttle,” he wrote in a 2009 reflection on his experience there. “We were subjected to a sizable dose of propaganda, but between two obligatory sessions of Socialist kowtowing, our hosts allowed us an amount of free walking unequalled since.”

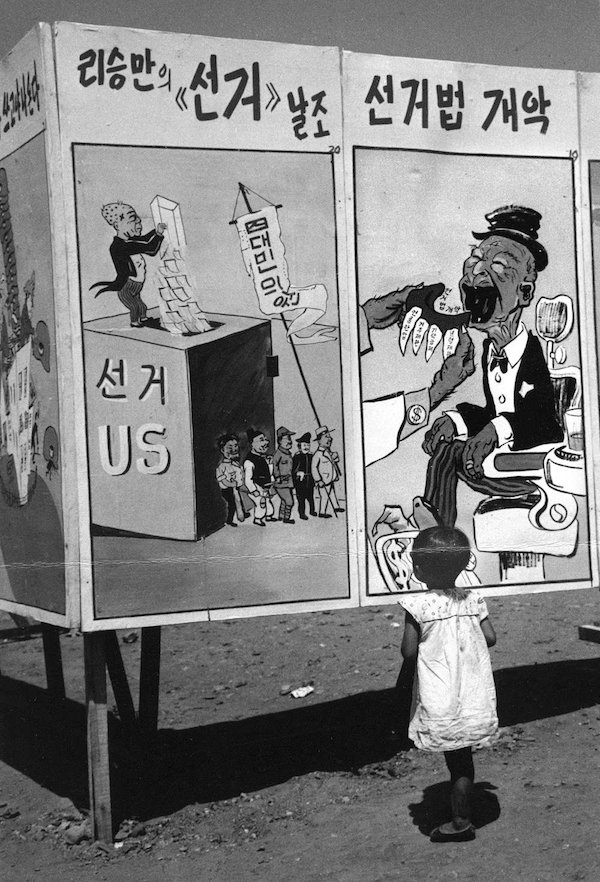

This resulted, ironically, in Coréennes‘ rejection “on both sides of the 38th parallel. To the North, a book which never mentioned once the name of Kim Il-sung simply didn’t exist. To the South, the raw fact that it had been allowed to be done in North Korea made it a tool of communist propaganda.” Thereafter, “Time froze on that country whose culture had fascinated me, as well as the mesmerizing beauty of its women, while the megalomaniac leadership of both Kims had proven a disaster.” Marker, who died on his 91st birthday in 2012, lived to see the beginning of the rule of the third and latest (and already, according to his detractors, no less disastrous) Kim, though not to see his regime’s recent news-making actions including the possible assassination of his half-brother and the launch of a missile aimed in Japan’s direction.

That most recent missile might have brought the amusing memory of a previous one to Marker’s mind. “What did we go looking for in the fifties-sixties in Korea, in China, and later in Cuba?” he asked in 1997. “Above all – and this is so easily forgotten today, with the hocus-pocus over that uncertain concept of ‘ideologies’ – a break with the Soviet model.” They never found it, but North Korea struggled harder to forget its onetime patron. “When the DPRK (that’s its official name) launched the famous rocket that worried the whole world,” Marker wrote in 2009, “the KOREAN NEWS agency published the following communiqué: ‘The Secretariat of the C.C., the Communist Party of the Soviet Union fully supports the steadfast stand of the Workers’ Party of Korea led by General Secretary Kim Jong Il.’ Yes, you read correctly: ‘Soviet Union.’ In 2009. Perhaps nobody ever dared to update comrade Kim Jong-il.”

Related Korea Blog posts:

Lost in Seoul, a New York Poet’s Memoir of Marrying into a Transforming Korea

Isabella Bird Bishop: Pioneering Female Traveler and Prototypical Westerner in Korea

The Adventures of Percival Lowell, Famed Astronomer and Early Writer on Korea

The Real Life of Seoul, as Seen by Street Photographer Michael Hurt

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.