Korea scholar Matt VanVolkenburg writes one of my favorite blogs on Korean society and culture, Gusts of Popular Feeling. It takes its unusual name from a quote from the 19th-century writer Isabella Bird Bishop, who in her book Korea and Her Neighbors (which you can download free, in a variety of formats, at the Internet Archive) observed that “gusts of popular feeling which pass for public opinion in a land where no such thing exists are known only in Seoul.” What can she have meant by that memorable if cryptic phrase?

“She was referring specifically to newspapers, what we consider modern public opinion as created through newspapers, through media,” VanVolkenburg told me when I interviewed him on my podcast Notebook on Cities and Culture. “But ‘gusts of popular feeling’ — Koreans will sometimes ask me, ‘What does that mean?’ I’ll be like, ‘naembi munhwa,’” a phrase often used to describe the national temperament. “A naembi is a pot that heats up very quickly and cools down equally quickly” — munhwa means culture — “and I just thought that was a very poetic way of describing it.”

The coiner of that poetic phrase turns out to have led a colorful life indeed. The daughter of a reverend educated at home due to poor childhood health, Bishop published her first written work, a pamphlet on the arguments for free trade versus protectionism, at the age of sixteen. She first went abroad to the United States six years later, sending home letters that would become the material for her first book, the 1856 travelogue An Englishwoman in America. Over the next four decades, volumes on Scotland, Hawaii, Australia, the Rocky Mountains, Japan, the Middle East, and Tibet followed, and in 1898, in her late sixties and a few years widowed, she would publish Korea and Her Neighbors, a thorough examination of a then-barely known land.

“Over three years, she made several visits,” said VanVolkenburg. “At first she didn’t really like it, but then on a return visit, she noted that Seoul had cleaned up quite a bit. She got to meet quite a few Korean people, and it definitely grew on her.” She made those visits between 1894 and 1897, “a very small window of time” during which Korea, having recently submitted to Japanese colonial rule, went through a big transformation. By 1904, the year of Bishop’s death, the capital “had streetcars, limited electricity, telephone, telegraph, waterworks were being installed — there were changes like that happening reasonably quickly.”

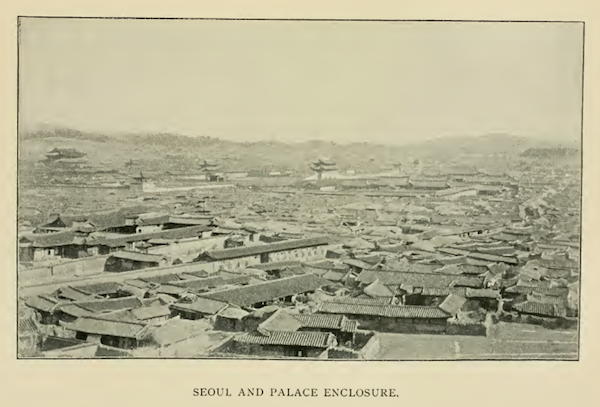

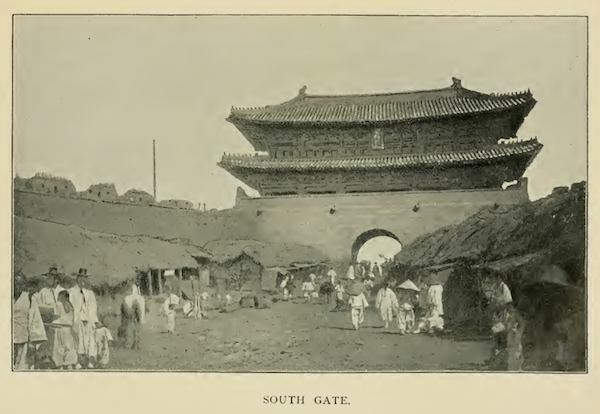

But the Korea on which she first set foot, a country more than half a century away from division into North and South and only just emerging from a long period in China’s shadow (which left Korea “but a feeble reflection of her powerful neighbor”), didn’t start from a high developmental baseline. “I thought it the foulest city on earth till I saw Peking,” she writes of her first impression of Seoul, “and its smells the most odious, till I encountered those of Shao-shing.” She considers its “palaces and its slums, its unspeakable meanness and faded splendors, its purposeless crowds, its mediaeval processions, which for barbaric splendor cannot be matched on earth, the filth of its crowded alleys, and its pitiful attempt to retain its manners, customs, and identity as the capital of an ancient monarchy in face of the host of disintegrating influences.”

Though she brands the city as “the Korean Mecca,” she remarks that “the monotony of Seoul is something remarkable. Brown mountains ‘picked out’ in black, brown mud walls, brown roofs, brown roadways, whether mud or dust, while humanity is in black and white.” And though “to the Korean it is the place in which alone life is worth living” — a view quite possibly as widely held now as then — most any part of it bears a dispiritingly close resemblance to any other settlement in the country: “Take a mean alley in it with its mud-walled hovels, deep-eaved brown roofs, and malodorous ditches with their foulness and green slime, and it may serve as an example of the street of every village and provincial town.”

Yet she reserves even more revolting descriptions for the conditions in those villages and provincial towns where her treks around Korea require her to spend days, even weeks, staying in and traveling between by land and water. Of lodgings she finds in one such place north of Seoul, she writes that “the family room which I occupied, only 8 feet 6 inches by 6 feet, was heated up to 85 degrees, was poisoned with the smell of cakes of rotting beans, and was so alive with vermin of every description that I was obliged to suspend a curtain over my bed to prevent them from falling upon it.” She finds better classes of quarters elsewhere, but even they “would not at home be considered fit for the housing of a better-class cow.”

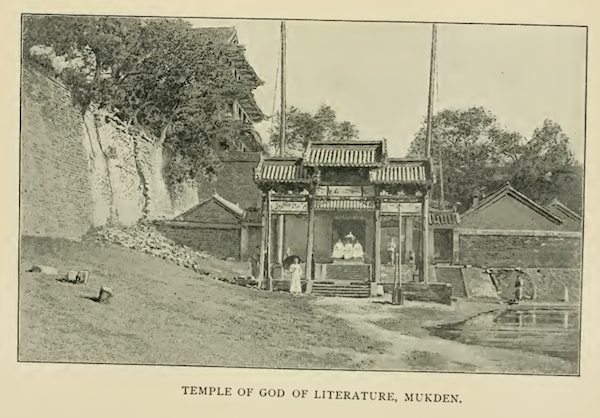

“As I sat amidst the dirt, squalor, rubbish, and odd and end-ism of the inn yard,” she writes, recalling a low moment, “surrounded by an apathetic, dirty, vacant-looking, open-mouthed crowd steeped in poverty, I felt Korea to be hopeless, helpless, pitiable, piteous, a mere shuttlecock of certain great powers, and that there is no hope for her population of twelve or fourteen millions, unless it is taken in hand by Russia, under whose rule, giving security for the gains of industry as well as light taxation, I had seen Koreans in hundreds transformed into energetic, thriving, peasant farmers in Eastern Siberia,” a time which, along with a stretch in Manchuria, makes up one of this long book’s interludes among the “neighbors.”

On her third visit to Korea, in 1897, Bishop finds much of Seoul, “literally not recognizable. Streets, with a minimum width of 55 feet, with deep stone-lined channels on both sides, bridged by stone slabs, had replaced the foul alleys, which were breeding-grounds of cholera. Narrow lanes had been widened, slimy runlets had been paved, roadways were no longer ‘free coups’ for refuse, bicyclists ‘scorched’ along broad, level streets, ‘express wagons’ were looming in the near future, preparations were being made for the building of a French hotel in a fine situation, shops with glass fronts had been erected in numbers, an order forbidding the throwing of refuse into the streets was enforced.” Seoul, she marveled, “from having been the foulest is now on its way to being the cleanest city of the Far East!”

Even then, Bishop describes a Korea in most ways not recognizable to the Westerners who arrive in Seoul today, marveling as they do at its outwardly greater development than that of the countries they came from. (They tend especially to like downtown’s restored Cheonggyecheon Stream, which Bishop describes, in its un-restored condition, as “a wide, walled, open conduit, along which a dark-colored festering stream slowly drags its malodorous length, among manure and refuse heaps which cover up most of what was once its shingly bed.”) But the ones who stick around tone down their marveling sooner or later, and the complaints they start to make have a way of echoing Bishop’s first displeased reactions to what had struck her as “the most uninteresting country I ever traveled in.”

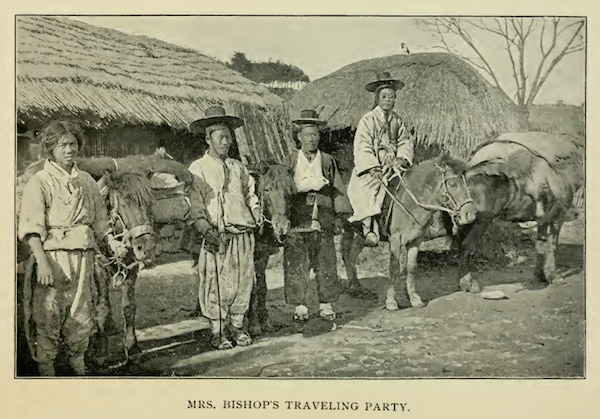

But Bishop, far from being a mere complainer — or in the parlance of her homeland, always more nuanced on the subject of negativity, a moaner — lived as one of the most accomplished members of one of the most accomplished generations of English travel writers, who remain, in the words of Christopher Tayler reviewing Colin Thubron’s last book, “one of the last types of writer on earth with a license to trade openly in the strange and beautiful.” At 459 pages plus index, appendices, and photographs (Bishop went nowhere in Korea without camera and tripod), Korea and Her Neighbors contains plenty of the strange and beautiful. It also spares few details of any other kind, assured that even the most adventurous of its 19th-century readership (who nevertheless require no further description of kimchi than as “an elaborate sort of ‘sour kraut’”) needed all the help they could to imagine this remote country, would likely never see another image of it, and almost certainly wouldn’t even consider taking the trouble to go there themselves.

If the heyday of English travel writing mandated the duty of describing places vividly through a sheer volume of information, it also mandated the duty of evaluating them, of making as fair as possible an assessment as a representative of the world’s most proudly “civilized” nation. Bishop’s frankness in this undertaking, and indeed the perspective from which she performs it, render a book like this terribly unfashionable today: she writes up front of her “plan of study of the leading characteristics of the Mongolian races,” later of “the Oriental vices of suspicion, cunning, and untruthfulness,” and later still of the superstition that “holds the uneducated masses and the women of all classes in complete bondage.”

Yet having invested an amount of time, effort, and endurance in Korea that any modern travel writer would consider well beyond their job description (let alone their pay scale), Bishop also places herself well to see the good in the country. Her position as a path-breaking female traveler, and one not only in a land with few foreigners but that did its utmost to keep even its own women behind closed doors, let her perceive clearly the relative safety that remains a real point of appeal today: “It says something for the security of Korea that a foreign lady could safely live in a dwelling up a lonely alley in the heart of a big city, with no attendant but a Korean soldier knowing not a word of English, who, had he been so minded, might have cut my throat and decamped with my money, of which he knew the whereabouts, neither my door nor the compound having any fastening!”

She also grasps Korea’s potential at a time when few others did. “With a splendid climate, an abundant, but not superabundant, rainfall, a fertile soil, a measure of freedom from civil war and robber bands,” she figures, “the Koreans ought to be a happy and fairly prosperous people.” She puts their deficiency of happiness and prosperity down to capricious law enforcement and taxation, as well as the economic “squeezing” of nearly the entire population by the country’s powerful classes of corrupt officials and ostensible scholar-aristocrats. She anticipates a time when, “with improved roads, railroads, and enlightenment, together with security for the earnings of labor from official and patrician exactions, the Korean will have no further occasion for protecting himself by an appearance of squalid poverty, and when he will become on a largely increased scale a consumer as well as a producer, and will surround himself with comforts and luxuries of foreign manufacture,” essentially the situation of the Korean middle class Korean today.

Alas, the heyday of English travel writing came during the longer heyday of British imperialism, and Bishop’s sympathies with that project — though in many ways a woman ahead of her time, she was unavoidably of her time in others — will bother more than a few 21st-century readers. She credits what improvements she saw Korea make to Japan, an imperial power with resemblances to Britain: “The Japanese claimed that their purpose was to reform the administration of Korea as we had done that of Egypt,” she writes, “and I believe they would have done it had they been allowed a free hand.” But they did not, and she ultimately finds that Japan “was too inexperienced in the role which she undertook (and I believe honestly) to play, to produce a harmonious working scheme of reform.”

“Failure in tact was,” as she sees it, “was one great fault of the Japanese.” In Korea, Japan “irritated the people by meddlesomeness in small matters and suggested interferences with national habits, giving the impression, which I found prevailing everywhere, that her object is to denationalize the Koreans for purposes of her own.” That, more or less, has become the official view in South Korea today, though it ascribes much graver faults to the Japanese than those of tact. Bishop’s lack of direct condemnation for the occupation itself puts her on the wrong side of the history books here, as does her revelation of the squalor and misery of the chaotic final days of an era much romanticized by historical films and television dramas.

She does convey the senselessness and brutality of the murder by Japanese agents of Empress Myeongseong, whom she knew personally (if not quite liked) as Queen Min, which occurred one night between her stays in Korea. I happened to read the chapter of Korea and Her Neighbors covering that grisly event in the cafeteria of the IKEA opened in a couple years ago just outside Seoul, perhaps the most incongruously modern and peaceful setting imaginable, one in which you can’t help but reflect on how much the country had changed. It made me wonder what Bishop, who didn’t live to see the Great War, let alone the Korean one, and who in a moment of optimism guessed that the whole peninsula “could support double its present population,” would think of the almost unfathomable developmental progress of the land she referred to as “southern Korea,” its population alone exceeding 50 million, has made over the past 120 years.

There are now plenty of newspapers, and though those gusts of popular feeling have gained force mainly on the internet, they still do blow through Seoul. While Bishop would recognize almost nothing about the city itself — its historic buildings tend to be 20th- or even 21st-century recreations — she would certainly recognize the attitudes of Westerners here. Korea and Her Neighbors documents how, as gradually as it may have done so, the country finally captured her imagination. Though many new arrivals these days go through a pre-complaint period of blind rapture over the amenities, the nightlife, and the the pop culture (none of which, apart from the ubiquitous underfloor heating, existed in the 1890s), it still holds true that “Korea takes a similarly strong grip on all who reside in it sufficiently long to overcome the feeling of distaste which at first it undoubtedly inspires.”

In this sense, even more so than the American astronomer Percival Lowell, whose own book-length travelogue Chosön, the Land of the Morning Calm came out in 1885, Isabella Bird Bishop stands as the prototypical long-term Westerner in Korea, for whom antipathy turns to fascination, and fascination turns to attachment, and attachment renders bittersweet the seemingly inevitable departure. “The distaste I felt for the country at first passed into an interest which is almost affection,” she writes near the book’s end, “and on no previous journey have I made dearer and kinder friends, or those from whom I parted more regretfully.” And somehow, at least to this long-term Westerner in Korea, its potential feels at once more fully realized and more untapped than ever.

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.