Book-length first-person narratives by Westerners in Korea have so far come in two waves: one in the 1890s, and another in the 1980s. Or perhaps, given that they produced only a handful of works each, long-form first-person narratives by Westerners in Korea have had more like two splashes. But though few in number, these books have held up through the decades: here on the Korea blog, I’ve already written about Percival Lowell’s Chosön, the Land of the Morning Calm: A Sketch of Korea and Isabella Bird Bishop’s Korea and Her Neighbors, both published in the 1980s, both earnest, witty, and by modern standards massively detailed attempts to replicate in text the life and landscape of an obscure and frustrating but ultimately endearing country few of their readers could imagine, let alone visit for themselves.

The second wave, or splash, of Korea books happened in the run-up to the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, an event now regarded as the reconstructed South Korea’s debut on the world stage. Simon Winchester, the writer of popular history and a traveler of British Empire vigor, took the whole country on foot and published his experiences in 1988 as Korea, a Walk Through the Land of Miracles. The journalist Michael Shapiro spent a year here around that same time, chronicling the country’s transition from military dictatorship to democracy in 1990’s lesser-known The Shadow in the Sun: A Korean Year of Love and Sorrow, which interspersed his high-level political observations with everyday ones about life in the country he briefly called home.

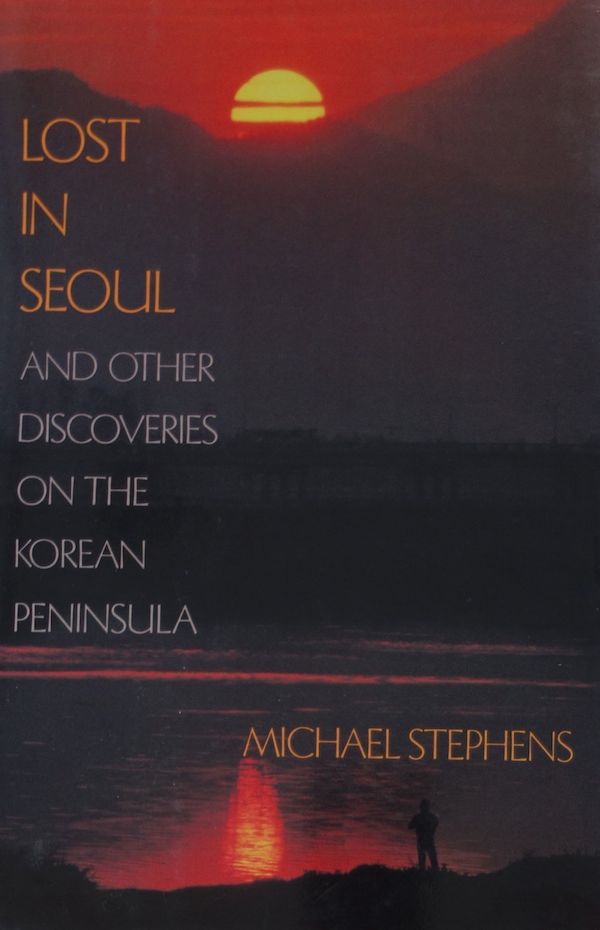

That same year, another American Michael, the poet and playwright Michael Stephens (also professionally known as Michael Gregory or M.G. Stephens) came out with Lost in Seoul and Other Discoveries on the Korean Peninsula. An inversion of Shapiro’s proportion of the political and the personal, the book draws on the New York-born, New York-raised, New York-based Stephens’ marriage to a Korean woman, and five or six of the visits they made, young daughter in tow, back to her homeland in the 70s and 80s. Its fourteen essays, all framed by his interactions with the pseudonymous family Han and their culture, find ways deal with Korea’s history, language, and politics, but also its variety of cultures: commercial, military, shamanistic, drinking.

The marriage put Stephens among a colorful cast of Korean characters, not least his chain-smoking, eyeshadowed opera singer wife, here called Haeja, the only member of her family to have settled in America. She’s spent a full decade away by the time of their first trip to Seoul together, meant in large part to introduce the family their two-year-old daughter Fionna (who, in real life, grew up to become the filmmaker Mora Stephens). A pack of excited relatives comes to pick them up from weary old Gimpo Airport, Korea’s only port of entry by air at that time long before the construction of the perpetually award-winning Incheon International. But soon an air raid drill — just like the one that opens Chil-su and Man-su — has halted all traffic into the capital.

“Haeja, Fionna, and I climb out after the Hans,” Stephens writes. “The siren whines and whines incessantly, and I half expect that we’ll all be diving for cover under the cars, hands over our heads, waiting for an incoming artillery from the lunatic communist horde.” Fear soon gives way to fantasy: “I’m already composing the copy to be smuggled out of the city at dusk via medivac helicopter to an American military base in Japan, where it’ll be wired to the New York Times — which will of course run it on the front page under my byline.” Passages like this, and others on the U.S. as well as the protest-bashing local military presence in the streets, capture the martial tone of South Korean life that lingers to this day, though (the occasional unexplained siren aside) the air raids have long since ceased, the tear gas he smelled in the streets has dispersed, the American soldiers seldom stray far off base, and the Korean ones look younger and more harmless by the year.

Even in the late 1970s, the regimentation of the postwar period had begun to loosen up, though the book opens with Stephens in a South Korea still run by developmentalist strongman Park Chung-hee. “Any day,” he reflects while making his way through busy market alleyways and factory-thickened air, “this nation will slough off that label ‘third world.’” In the only scene of his and Haeja’s life in New York, he gets home after day his university job to the news of Park’s assassination by his own security chief. Grimly fascinated, he can’t stop himself from asking questions about the event on his next visit to Korea, even as he dines on pseudo-French cuisine high up in the newly built Lotte Hotel — albeit early, “in order to have a full evening on the town before curfew,” adhering to the terms of the martial law then in effect.

By the final chapters, with the Olympics looming, the Koreans around Stephens have begun to speak of democracy in non-hushed tones, even at as staid a gathering as his mother-in-law’s sixtieth birthday party. He describes the event, which celebrates the most important age milestone one can pass in Korean culture, as “like those gala balls found in nineteenth-century Russian novels.” Indeed, Seoul itself “reminds me of Moscow a century earlier, or should I say, it reminds me of that city I think I know from Russian literature of a century ago.” That may reflect his elevated coterie: Haeja’s family, though not, strictly speaking, aristocratic, maintains powerful government and business connections, and most of its members live in a large, servant-staffed traditional Korean courtyard house, renovated by Haeja’s architect-scion stepfather and located right next to the residence of the president.

That, combined with the very title Lost in Seoul, leads one to expect a standard memoir of the coddled, uncurious, and often hired American abroad. Standing at a deliberately uncomprehending distance, they grind out interminable pages of futile struggle with laughable foreign customs, unappetizing foreign food, and incomprehensible foreign language — the sort of thing, in other words, that hit its intellectual apex with Dave Barry Does Japan. But in many ways, Stephens has written the opposite of that, the story of his ever-deepening relationship with, especially at the time, a poorly understood and little-respected culture.

“I grew up with bitter old men cursing the Korean peninsula because they fought a dirty war there,” he writes, scraping together whatever impressions of the country could have preceded his marriage to one of its people. “Their minds were filled with images of rubble, gutted landscapes, biting chill, Chinese hordes, napalm, claymore mines, frozen ghosts.” Whether meeting Haeja drained these frightening second-hand memories of their power or sparked a latent interest in Korea he doesn’t say; in fact, he says nothing of the courtship at all, though he does make several connections, explicitly and implicitly, between his wife’s heritage and his own.

“Her crazy face reminds me of a redheaded Irish aunt with a bottle of whiskey in her,” he writes of a Korean spirit medium deep in the throes of exorcism. “The Irish of Asia,” once the standard shorthand description of the Korean people, evokes hard work, binding family ties, and, not unrelatedly, hard drink. But like many Westerners in Asia, even those married into the society, Stephens enjoys a certain degree of freedom from societal expectations, and even faux pas — smoking in front of his elders, giving too-colorful ties as gifts — stay off his permanent record. Not so Haeja, who immediately upon stepping onto Korean soil again becomes, in an official sense, “a wife and mother, two important roles to add to her repertoire in this familial world, where she is already daughter, sister, and aunt, each with its own complex decorum.”

Despite the comforts of the Han household and its accommodations (including but not limited to an order given to its servants to replicate a daily “American breakfast” as best they can), Stephens eventually chafes against it as well. Hence the titular state, which he finds “sometimes the only way for me to experience Korea away from the overprotectiveness of Haeja’s family. When they are not too carefully watching out for my well-being, they are often too caught up in the pride of being Korean, in wanting to show their Western relative an airbrushed, charming side of Seoul.” Not a scene in the book takes place in, say, the subway (the Hans keep a driver, or drivers, always prompt with the pick-up), or in one of the lookalike tower blocks already on the way to becoming the standard form of Korean housing in the 1960s.

Yet Stephens develops a keen eye for the city, then as now “a hodgepodge where the wealthy, the middle class, and the poor live side by side.” The concentration of wealth in what this book refers to as New Seoul, now far better known in the West as Gangnam, has since introduced more segregation into the cityscape, but visitors from other countries still quickly take notice of the relative proximity of the seemingly disparate, from social classes to architectural styles. Nor does its distinctive religious iconography escape them, as it doesn’t Stephens, who takes early note of a mountaintop atop which “a huge neon cross proclaims JESUS SAVES!” — and, in another direction, a Buddhist temple. “My eyes freeze,” he writes, “on a swastika painted just under the rooftop.”

His attempts to get a handle on the distinctive morality and philosophy underlying Korean society lead Stephens to pronounce its people “Confucians socially, Buddhists when times are difficult, but they are animists nearly always.” The dynamic between the sexes, in which “men flaunt power” while “women finesse theirs,” comes explained to him mostly by the men in Haeja’s family, or at least those who willingly bring him into the Korea’s closed masculine circles. Much of it comes from the expansive, gregarious, aspirational (and also English-speaking) Uncle Mo, would-be quasi-royalty severed from the benefits of his pedigree by his illegitimacy. “Write about the women,” goes his advice to Stephens about his book in progress, “but always remember that Korea is a great country for men.”

And just a few pages later: “If you are going to write about Korea, forget about the men. The women are the real story because everything about them is so subtle, nothing is what it appears to be.” He says this during the same driving range coffee-shop conversation in which he describes himself as a feminist and during which — “it is difficult for me to act like anything but a man in public” — he gruffly orders around and leers animalistically at their waitress, neatly demonstrating what might look to a Westerner like the unhealthy contradictions of Korean gender relations. “For most men, romance comes outside the home,” says another middle-aged Korean man, providing a clarifying addendum to another lecture of Uncle Mo’s, delivered in the locker room of another golf course. “’This is so,’ agrees a businessman, toweling himself off.”

One personality has more vividness on the page than Uncle Mo: the diminutive, foulmouthed, Grandma Oh, long-widowed and with nothing to do but drink, smoke, and issue various complaints and pronouncements — to “be herself,” in other words, “as irascible and unhappy as that self may be, and accept everyone’s esteem for her. Americans would have sent her to a nursing home long ago. In a Korean household, she is not just tolerated, she is venerated as the great elder of the family.” Then as now, Koreans tend to regard those past the age of about eighty, coarsened, stiffened, and stunted by the sheer difficulty of their lives, as living totems of their country’s hardships. As, in a way, does Stephens: “I feel that if I can explicate the furrows, the cracks, the wrinkles, the deep lines on her cheeks and her brow, in her chin and along the bridge or her nose, I would understand all there is to know about modern Korea.”

Sometimes, these bent and cranky senior citizens also become unlikely fonts of progressivism, Grandma Oh being no exception: “There’s nothing wrong with a good woman marrying twice,” she declares more than once. “Nothing at all. This is a new era.” Haeja’s mother, after the death of her own first husband, remarried herself, doing so in an era when such an act would have put her decidedly on the vanguard. Despite having been born in 1896 (just a year after “the great matriarch Queen Min had been assassinated by Japanese gangsters,” an era-ending death recounted in detail by Isabella Bird Bishop), Grandma Oh understands the changes sweeping South Korea better than the younger people who supposedly represent them, from the foreign-educated relatives with their surly demands for justifications for every tradition to the teenage Korean-Americans shipped in ostensibly for cultural enrichment. “I imagine that Korean parents driving by probably point them out to their children as examples of what will happen to them if they’re not good,” Stephens says of one such group, dyed of hair and theatrically irreverent of manner, hanging out on a street corner.

A Seoul city block can change unrecognizably in a matter of months, or even weeks, a pace already set when Stephens first arrived on a background where “about every third building, there is an excavation,” to a soundtrack of “jackhammers, honking horns, whistles, shouts and combustion.” It must owe, then to his sense of the timeless that the neighborhoods through which he describes wandering (when not chauffeured), despite thirty or more intervening years, remain recognizable in the text today. Seoul, as he puts it late in the book, “is where I gather myself, where I put myself back together” on each trip he, Haeja, and the teenage Fionna (fast growing, in Stephens’ description, into of those increasingly alien Korean-Americans herself) eventually make each rainy summer season during the university break.

Lost in Seoul‘s editor at Random House certainly demonstrated foresight in shepherding the book to publication — maybe too much foresight. Korea had, for the first time since the war, become a big subject in America in the late 1980s, albeit not quite big enough to eclipse the even more astonishing, and thus more anxiety-inducing, rise of Japan, its larger, outwardly sexier neighbor as well as former colonizer. (This opened a river of first-person Westerner’s narratives of Japan, not just by Dave Barry, that still hasn’t quite run dry.) But more than fifteen years of economic stagnation having since neutralized the Japanese threat, the Land of the Rising Sun has lost some ground to the Land of the Morning Calm as an Eastern site of Western cultural interest. It helps that Korea now wields “soft power” in the form of pop music, films, television dramas, and even literature, whereas in the 70s and 80s it seemed to offer practically nothing of potential international interest — in other words, nothing cool.

But Stephens, a self-described rumpled academic who first brought to Korea little more than his knowledge of “basketball, open-form American poetry, western drama, Buster Keaton, I Love Lucy, and Thelonious Monk,” has little concern for the cool. But his interest in poetry provides him a lighted tunnel into the deep culture of Korea, a place where it holds popularly acknowledged primacy over all other literary forms. My copy of Lost in Seoul came, seemingly untouched, straight from the estate of a Pacific Northwest poetic luminary. Inside I found a letter written to her by Stephens himself: “As the enclosed book is as much about language, and specifically poetry, as it is about Korea,” it begins, “I thought it might interest you.”

Stephens incorporates his own translations of Korean poetry in the text, and references to the Western variety appear with some frequency. (He titles the third chapter “Tea at the Palaz of Hoon.”) But the interest in the Korean language itself sets him apart, to my mind, from his contemporaries, not just in the endeavor of writing about Korea, but in the endeavor of joining and understanding, to the extent possible, a Korean family. (Most of the first Korean-married countrymen I met, in the late 1990s, didn’t just know little of Korea but insisted on calling their wives by their comically bland “American” names.) He devotes much of another referentially titled chapter, “Politics and the Korean Language,” to the complications of speaking it in the particular way properly suited to one’s age, status, and origin. He even develops a certain ungrammatical, drink-lubricated fluency in the language himself, which is more than many long-term expatriates here can say for themselves.

In the letter paperclipped into my copy of the book, Stephens also mentions that it “has not yet received too many reviews” despite several months on the market. Now based in London, he seems not to have written much about Korea since, and though Lost in Seoul remains reasonably easy to come by at the better libraries (I first read it at the Koreatown, branch of the Los Angeles Public Library, when I lived in the neighborhood), I have yet to meet anyone, in America or in Korea, who recognizes the title. Ironically, this long-out-of-print book now has more relevance than ever given the West’s rising Korea-consciousness, as well as the incomparably more thorough integration of Koreans into the outside world.

Back in the era of air raid drills and political assassinations, a Western family member was still a novelty; now at least half of my American friends have married someone from Asia. The only one of them who’s yet read this book on my recommendation happened to marry a Korean woman himself: he has, forty years after Stephens’ experiences, his own Haeja, his own regularly South Korea-stamped passport from visits to his own Hans, and as of this year his own Fionna. Whether he’ll take the next logical step and write his own Lost in Seoul remains to be seen, but I sense that the time has in any case come for the book-length first-person narrative by Westerners in Korea, whether in another splash or that long-awaited wave, to return.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Isabella Bird Bishop: Pioneering Female Traveler and Prototypical Westerner in Korea

The Adventures of Percival Lowell, Famed Astronomer and Early Writer on Korea

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.