On a pedestal high above downtown Seoul’s Gwanghwamun Square stands Admiral Yi Sun-sin. Generation after generation of Korean schoolchildren have studied the 16th-century naval commander’s unblemished record of victory against the invading Japanese, and four centuries after his death Yi remains the unrivaled symbol of a small, impoverished nation’s will to resist predation by the larger powers surrounding it. His statue was erected in 1968 at the behest of Park Chung-hee, the military dictator who had taken power in a coup d’état seven years before. Park ordered only that the monument depict the Korean most feared and admired by the Japanese who, with Yi long gone, had finally colonized Korea in 1910 and remained in power there until the end of the Second World War.

By the time the Korean War came to its prolonged halt in 1953, the Korean Peninsula was a divided shambles. But at the end of the 20th century, its fully industrialized and democratized southern half boasted a standard of living nearly equal to that of its loathed (but for its economic dynamism, grudgingly respected) former colonial master. How much need remained to mythologize a military figure from the distant past, or for the anti-Japanese sentiment inflamed by official depictions of Admiral Yi and channeled by the likes of Park to rally the South Korean public behind the project of nation-building? Yi has long drawn comparisons to Horatio Nelson: as a masterful and unconventional naval tactician shot down amid his final victory, as the personification of a certain idea of a nation’s spirit, and as the hero of often-told tales. The considerable respect for Admiral Yi by ordinary Koreans has not always been accompanied by a pressing desire to hear his story told once more.

Yet just after the turn of the 21st century, the story of Yi Sun-sin did indeed seize the attention of the Korean reading public afresh. It did so in the form of the novel Song of the Sword (칼의 노래) by Kim Hoon, a career journalist who — in this country transformed seemingly overnight from one of the victims of history into a technologically savvy exporter of cars and computer components — had never driven a car nor used a computer. Kim’s project, articulated plainly, may also have sounded like near-sacrilege: to write not just from the Admiral’s point of view, but in the Admiral’s voice. Drawing on Yi’s own war diaries, Kim needed not invent that voice out of whole cloth, but the clipped, resoundingly unsentimental narration with which the Yi of Song of the Sword relates the final two years of his life nevertheless made an impression on readers who had only perceived their national hero through the grandest, most elevating language. If Yi is Nelson, Song of the Sword is Nelson as rendered by Hemingway.

“Flowers blossomed on each deserted island,” says Yi, delivering the novel’s opening words in an excerpt translated by Jung Ha-yun and Ahn Jin-hwan. “The islands billowed like clouds as the evening sun lit the flowering trees. It seemed as if they might slip free of their moorings and drift beyond the darkening horizon.” The year is 1597, and the place is the southeastern coast of Joseon, the name of the kingdom then ruling the whole of the Korean Peninsula. Though already an accomplished combat veteran, the middle-aged Yi has been stripped of his rank after a period of imprisonment and torture at the hands of his own government, and not for the first time: a decade earlier it had come as the consequence of a false accusation of desertion, and this time of Yi’s disobeying an order to lay an ambush based on information from a distrusted double agent. The spy, so history records, had been deliberately sent by Japan, whose ruler Hideyoshi Toyotomi was engaged in a years-long campaign, repeatedly thwarted by Yi’s defenses, to capture Joseon as a base from which to conquer China.

Reduced to the rank of a common soldier with the entire naval hierarchy above him, Yi contemplates “the moment when the enemy fleet would swoop in once again on the dark crest of waves from the other side of the murmurous horizon, wings spread wide, bearing a mountain of guns and swords. I could not fathom the source of the enemy’s rancor and the enemy had no way of knowing the quivering depths of my own rancor. The sea was taut, swollen with a rancor that neither side could hope to penetrate. But that was all I had for the time being — no fleet, only my rancor.” It is this bitter emotion — not a dream of heroism, not love for his people, and certainly not loyalty to his king — that motivates Yi to face and and beat back the Japanese ships until he meets his death, a death about whose proper manner and location he becomes increasingly obsessive.

Song of the Sword eschews historical sweep and ideological charge in favor of its narrator’s stark inner life, painting a picture of Yi Sun-sin as isolated and anxious — his interior monologue keeps returning to simple but increasingly dread-laden descriptive phrases like “The water was still” and “The enemy was approaching” — but nevertheless at one with the weaponized role that drives him to persist as well as to die: he is the sword, and the sword’s song is his own. Kim has credited days spent gazing at the Admiral’s sidearm, enshrined in the great man’s hometown of Asan, as the inspiration to begin writing the novel. What the sword is to Yi, the pencil is to Kim: “When I write with pencils, I feel that my body is propelling the writing forward,” he has said. “I am incapable of writing a single line without this feeling.” This is the self-description of a novelist more accustomed to writing about men of action than men of letters: his first novel Memories of Comb Tooth-Patterned Earthenware (빗살무늬토기의 추억) is about an excavator operator turned firefighter, an occupation Kim’s 30 years as a newspaper reporter would have afforded him ample opportunity to observe.

Kim Hoon was born in Seoul in 1948, to a father who had also made his name as both a journalist and an author of historical novels. Unlike Song of the Sword, which both sold more than one million copies and won the Dong-In prize, Korea’s most prestigious literary award, Kim Kwang-ju’s newspaper-serialized tales of chivalry and court intrigue found commercial but never critical success. And despite the popularity of his work, he proved to be more prodigious a drinker than an earner. Kim Hoon first practiced the craft of fiction at his father’s bedside, taking dictation and assembling ideas on the page during the battle with cancer that consumed the three years before Kim Kwang-ju’s death in 1973. Kim Hoon’s younger sister entered college that same year, worsening the already strained family’s financial burden. All this forced Kim to drop out of Korea University, where had cultivated a love of Byron and Mary Shelley, and take up his father’s job at the newspaper.

Kim published Memories of Comb Tooth-Patterned Earthenware, his first novel, two decades later at the age of 47. When he followed it up with Song of the Sword seven years thereafter, some saw him as finally taking over the family business of historical fiction. But though Kim has continued to write novels set in Korea during the centuries before Japanese colonial rule, the very first pages of Song of the Sword announce a decisive aesthetic separation from the escapist fantasies of his father’s generation. Kim’s Yi Sun-sin, disaffected to the point of nihilism, would not have had a place in their books, nor would his frank descriptions of sights (often enough accompanied by smells) gruesome enough to challenge the imaginations of present-day readers. Yi surveys a coastline “blanketed with corpses, some with the head cut off, others the nose” — the score-keeping systems of the Joseon and Japanese militaries, respectively — and devastated swaths of the countryside where “the few villagers still breathing killed their children and ate their flesh.”

Black Mountain Island (흑산), a novel Kim sets amid Joseon’s Catholic purges of the early 19th century, contains a detailed section on the importance of voiding one’s bowels in the likely event of an anal rupture inflicted during a bout of flogging, then the Confucian elite’s standard punishment for those who professed the forbidden faith. Central to Song of the Strings (현의 노래), set on a sixth-century Korean Peninsula divided between three rival kingdoms and fast being depopulated by the ongoing warfare between them, is the custom of burying a dead king with thirty of his living subjects. Kim accords it the same descriptive treatment as he does the other event that grounds the book in history: the creation of the gayageum, the zither whose strings now define the sound of traditional Korean music, and the sight of which moved Kim to write much as that of Admiral Yi’s sword had done.

Namhan Mountain Fortress (남한산성) originated in Kim’s encounter with neither a weapon nor a musical instrument but the structure of the title, to which Joseon’s royal family and court fled in 1636 and inside which they subsequently spent 47 days behind barricades. The threat came not from Japan to the east, but from China to the west, specifically the newly ascendant Qing empire whose leaders had grown impatient with the tribute Joseon continued to pay to the Ming dynasty, which the Qing had displaced. The fortress still stands fifteen miles southeast of Seoul, and Kim has written of approaching its walls and realizing that the personal struggle within them must have held as much interest as the political and military struggle beyond them. The central conflict dramatized in the resulting novel erupts between those members of the Joseon court and royal family who favor capitulating to the Qing, and those who insist on a fight to the death — their own death, what with 13,800 soldiers inside the fortress against 70,000 laying siege to it.

Joseon surrenders to the Qing in Kim’s novel just as it did in history, concluding another chapter in the life of a land, and a people, faced in era after era with the choice between subjugation and extermination. What has characterized the lives of the kingdoms and states of the Korean Peninsula also characterizes the lives of Kim’s individuals: “Human reality cannot be made up solely of self-respect and glory,” Kim has written, articulating a view he has held at least since Song of the Sword. “I believe it is inevitable that shame and submission be a part of life and history as well.” Some critics interpret Kim’s treatment of the siege of Namhan Mountain Fortress as an allegory of South Korea’s 21st-century geopolitical situation, pressed in as it is between a fast-rising China, a still-distrusted Japan, and the grim embarrassment of North Korea — a reading the author himself, who ahead of Song of the Sword‘s main text includes an injunction to “read this novel as a novel,” would surely not countenance.

For South Korean writers and public intellectuals, history is both the safest subject and the most dangerous one. While they can use the distant past to take refuge from (or establish plausible deniability of investment in) present-day ideological struggles, they approach the Japanese colonial period and the formation of the Republic of Korea at their peril. A suggestion that Japan’s rule had positive consequences of any kind, or that modern South Korea drew its builders from the ranks of collaborators and cooperators as well as from those of Japan-hating patriots, can result in ostracism. Park Geun-hye, daughter of the Japanese-educated Park Chung-hee, blacklisted a variety of artists and other public figures for those and other offenses during her own time as president from 2013 to 2017. Her impeachment came after weeks of public protest — the many popular grievances against her included her party’s attempts to revise national history textbooks — in Gwanghwamun Square, beneath the statue of Admiral Yi.

On a throne just down the plaza sits another sculpture of another near-sacred historical figure: King Sejong the Great, who in the early 1440s commissioned the creation of hangul, the phonetic alphabet now used near-exclusively to represent the Korean language in writing. Before King Sejong’s reign, educated Koreans wrote using only logographic Chinese characters, or hanja, and indeed continued to do so until the middle 20th century, given the the easily mastered hangul‘s associations with the lower classes and women. A mixture of both systems of writing (much like the mixture of Chinese characters and phonetic alphabets still used in Japan) eventually emerged, but the subsequent emphasis on hangul under Park Chung-hee resulted in the virtual disappearance of hanja from public life by the end of the 20th century. The more abstract and technical half of the Korean vocabulary still comes from Chinese, a heritage comparable to that which Latin has bequeathed to the English language, but Koreans no longer use Chinese characters to represent most of it.

What hanja appear in Kim Hoon’s work, always enclosed in parentheses beside the hangul, identify specific historical concepts or entities. Though necessary, these terms sit somewhat awkwardly amid the kind of prose with which Kim has made his name since Song of the Sword, astringently spare and composed of sentences pared much further down than those of most Korean literary prose. The writing in his unsuccessful first novel, however, falls more in line with the expectations set by other Korean novelists of his generation. Memories of Comb-Tooth Patterned Earthenware opens with the following sentence: “Each time the guerrilla units of the wind stationed downtown swept through the narrow, deep valleys between the buildings and twisted around the corners, they changed direction and speed, leaping up high, and as the units that smashed against the walls of the buildings escaped out the city’s valleys and tangled with the other ranks rushing in from across the street, they got pinned to the ground or soared up to the sky, blowing trash into the air.”

But despite the relative indiscipline of its language, even that book shows signs of the aversion to the abstract and metaphysical that has since distinguished Kim ever more sharply from his peers. He never describes a character’s personality directly, conveying in only the most concrete terms their actions, their physical characteristics, their speech, and the often unpleasant physical sensations they experience. Only in recent years has he written of his potential willingness to use the Korean words for such concepts as love and hope. This makes him a veritable eccentric in a culture that sets great store by high-flown rhetoric and extravagant emotional display. The narrator of his short story “My Sister’s Menopause” (언니의 폐경) remembers having been commended at her mother-in-law’s funeral for her outpouring of sorrow, one so intense as to have made her appear to have mourned the dead woman “more genuinely than her own daughters.”

Set in the present day, “My Sister’s Menopause” stands out in Kim’s bibliography, not just for having won the Hwang Sun-won Literary Award (named in honor of a writer from the generation before Kim’s known for his stories of lower-class suffering and resilience) but for being narrated by a woman. A few years before the story’s publication in 2005, controversy erupted around an interview with Kim in which he called feminism an evil system of thought, equated female beauty with that of grass on a mountainside, and described patriarchal society as the most comfortable for women because it assigns the responsibility of dealing with life’s difficulties to men, the superior and more competent sex. He later explained his view of the inequality of men and women in terms of the sheer unknowability of one sex to the other, but that position eventually softened to the point that he took on the challenge of writing from a woman’s point of view, with results that drew praise even from younger and self-described feminist writers.

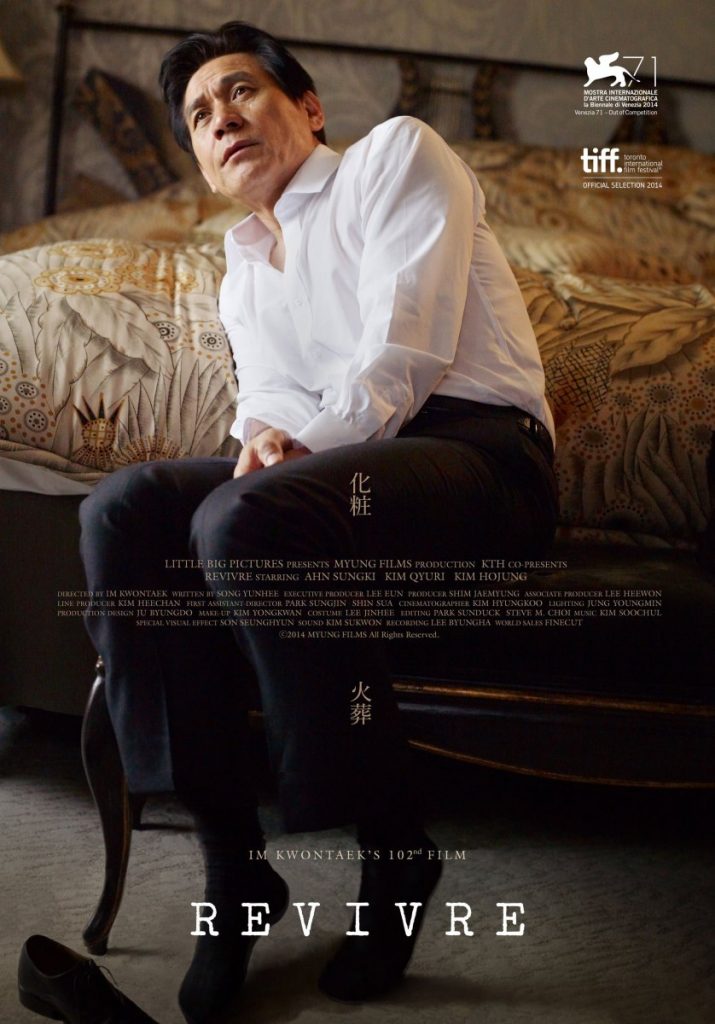

Male or female, Kim’s characters are thoroughly biological creatures; the erratic, voluminous final bouts of menstruation in “My Sister’s Menopause” rank among Kim’s most flatly harrowing passages. So do many of the scenes that constitute his even better-known and more prestigiously laureled 2004 short story “Hwajang” (화장), adapted in 2014 as Revivre, the 102nd film by veteran director Im Kwon-taek. The word hwajang translates to either “cosmetics” or “cremation,” and one proposed English-language title, “From Powder to Powder,” faintly reflects the presence in the narrative of both meanings: the 55-year-old narrator Oh Sang-moo’s all-consuming position as a marketing executive at a cosmetics firm, and the cremation Oh arranges for his wife after her death of brain cancer. The bereavement occurs amid other pressures, both figurative and literal: Oh’s colleagues immediately follow their words of condolence with inquiries as to his decision on the next season’s advertising campaign, and the discovery that he can no longer reliably urinate on command necessitates urgent visits to a clinic to have his bladder drained by a nurse.

The story’s most startling moment comes when Oh’s first-person narration shifts to directly address Choo Eun-joo, a young mother employed by his department. What at first sounds like a monologue of infatuation becomes a detailed, reverent, and ultimately unsettlingly clinical envisioning of Eun-joo’s body, both its exterior and its reproductive interior. Kim’s language here carries only slightly more of an erotic charge than that which he uses to render Oh’s memories of his wife’s final, wasting days, during which she can produce nothing but excretions and apologies. Eun-joo may represent to Oh a wellspring of life, but “Hwajang” ends with that wellspring having run dry: her diplomat husband receives a transfer to Washington, and she hands in her resignation with Oh away witnessing the industrialized procedure of his wife’s cremation. After Oh receives word of Eun-joo’s departure and acquiesces to the campaign proposal for which a colleague had been pushing, all that remains in the reduction of his life is to euthanize Bori, the dog that, as Oh justifies it to the veterinarian, now has no one at home to feed him. “That night, I slept deeply for once,” the story ends, “a sleep so deep my entire consciousness collapsed and evaporated.”

Oh’s wife chose the name Bori, the Korean term for Buddhist enlightenment, in hopes that the animal would be reborn a human. (Kim, who describes himself as a lapsed Catholic, makes the theme of rebirth manifest in several ways, including an uncanny resemblance between Oh’s daughter and her mother, and between Eun-joo’s baby and herself.) The canine protagonist of Dog (개), Kim’s novel of the following year, has the same name but with a humbler meaning behind it: barley, for which he and his litter share a hearty appetite. This reflects a difference in the observational sensibility between “Hwajang” and Dog, the latter of which is told entirely from Bori’s perspective, one low to the ground in every sense. Bori observes the affairs playing out among the small-town adults and children around him more concretely than do even Kim’s human narrators — and thus, in Kim’s worldview, more truthfully as well.

Bori relates exactly what he sees and hears, and nearly as often what he smells, offering Kim the opportunity to more consequentially explore the olfactory interests already evident in his human-oriented work. (Bori also has much to say about what he tastes, a potentially trying characteristic in a narrator given to odes about the deliciousness of human feces.) Whether or not Kim considered writing in the voice of a dog a challenge comparable to writing in the voice of a woman, he does frame it as a kind of moral mission. In the book’s foreword he writes of riding his bicycle through the kind of empty villages “people couldn’t live in and left,” where he once found himself approached by one of the friendlier of the many abandoned dogs wandering the streets. “In the black pads of the dog’s feet I saw all the pain, happiness, and dreams of the world,” he writes, and then and there “decided to bark for all the dogs in the world.”

Kim’s two-wheeled exploration of the lonelier parts of his homeland reflects a fascination with such places that has become a tendency to advocate for them, at least as subjects of narrative. Like fully half the population of South Korea, Kim lives within the Seoul metropolitan area, but he has had more literary use for the regions hollowed out for both political and economic reasons: the port town on the southwestern coast where a cast of societally marginal figures (a scrap-metal recovery entrepreneur, a Vietnamese migrant, a newspaper reporter not unlike Kim in his previous career) converge in his novel River of No Return (공무도하), or the practically uninhabited borderlands just below North Korea in which he sets a solemn love story in The Forest of My Youth (내 젊은 날의 숲). In that novel the daughter of a disgraced bureaucrat takes a job as a miniature-painter at an arboretum near the border, where she meets an army lieutenant working on a nearby excavation of human remains dating back to the Korean War.

The extensiveness of Kim’s travels throughout South Korea, and the extensive use he has made of them in both his fiction and nonfiction — including his two popular Bicycle Journeys (자전서 여행) essay collections — also stand out from Korean literary tradition. His bicycle must provide him as strong a sense of bodily propulsion as his pencil does, and the physicality of both tools draws a clear contrast against the Joseon-dynasty image of the scholarly, aristocratic yangban breaking his life’s idleness only to compose the occasional lines of classical Chinese verse in appreciation of the moon, the water, the mountains. Unusually for a Korean man of letters, Kim has published no poetry at all, though his propensity for compression over expansion does bring critics to ascribe poetic qualities to his prose. What’s more, he has found his greatest success with the novel, a form that in hangul goes back scarcely more than a century and is still looked on from some quarters as suspiciously foreign.

Kim’s only yangban tendencies manifest in his refusal to use 21st-century technology (itself the mark of a certain kind of aristocracy in a society where even poor octogenarians own smartphones), as well as in his appreciation of nature, to which he seldom goes more than a few pages without making reference. But when Kim describes a landscape, he usually does it to reflect the feelings of his characters, most often characters in extremis, whatever the time period or socioeconomic class they occupy. Their plights may look familiar to readers of modern Korean fiction, especially in English translation, which to Westerners can seem preoccupied with the unbearable physical and psychological traumas visited by history on blameless people. Writers in postwar Korea have often mobilized such visions of dislocation, desperation, and humiliation in service of political or ideological indictments of the still-new republic and arguments (both implicit and explicit) about about the direction it must take.

But the literary activism that has occupied so many of his colleagues holds no appeal for Kim, who speaks in the bluntest terms about what he considers the delusions surrounding literature, especially the belief that the pen is mightier than the sword. He was not, after all, moved to write a novel about Yi Sun-shin by the sight of a pen, and even telling the story of his country from the middle of the colonial period in the 1920s to the democratization of the 1980s in his latest novel In a Vacant Lot (공터에서) brings down no judgments on either his often unheroic characters or the historical currents that sweep them along. When Kim rejects ideology, abstraction, and even symbolism to more clearly perceive sensory experiences and the roles given to the men, women, and animals who undergo such experiences, his fellow Koreans ask “what side” he’s really on. Whether speaking or writing, he has answered consistently and unambiguously: “I’m on the side of those in pain.”

(Kim Hoon portrait source: Namuwiki; Gwanghwamun Square image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Related Korea Blog posts:

The Making of a Korean Monster: Kim Sagwa’s Bloody High-School Novel Mina

A Korean Literary Superstar Tells His Countrymen Why to Read

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.