I’ve got a trip to America planned next month, and even though I’ve only lived in Korea for three years, I now know more or less where to expect the moments of reverse culture shock. They begin with the uniforms, the contrast in which makes itself felt right away at the airport where I land. I’ve never had to fly an American airline out of Korea — knock on wood — but one look at the uniforms on their attendants, especially by comparison to the Korean-airline uniforms I’ve been seeing for the past dozen or so hours in flight, always underscores that I’ve left one society and entered another. Few American institutions not related to defense or law enforcement now seem to hold their uniforms in high regard, or even to demand much effort in the wearing of them. Sometimes their uniforms scarcely read as uniforms at all; I think, for example, of the Hawaiian shirts at Trader Joe’s, a beloved American institution unknown in Korea.

Only recently has it occurred to me that the difference between Korean and American uniforms reflects a difference in the value each culture places on androgyny. Emphasis on, let alone exaggeration of, classically male or female traits seems to have fallen into relative disrepute in America, regarded as unprofessional in some milieux and — ironically — insufficiently rebellious in others. If 21st-century American uniforms tend not just to be near-aggressively casual but sexless as well, so does 21st-century American dress in general. The same could certainly not be said of 21st-century Korean uniforms, nor of 21st-century Korean dress in general, nor of the many areas of Korean life and society where dress and uniform converge. Those areas provide the material for The Social Uniforms Project, an Instagram account on which a model and photographer collaborate to vividly depict the many uniforms, both official and unofficial, worn by modern Korean women, as well as the contexts in which they appear.

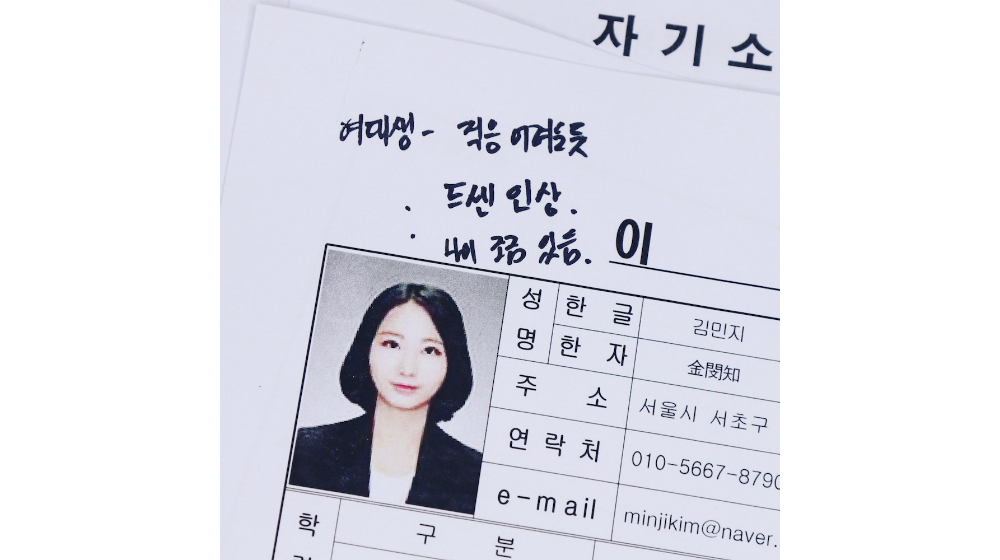

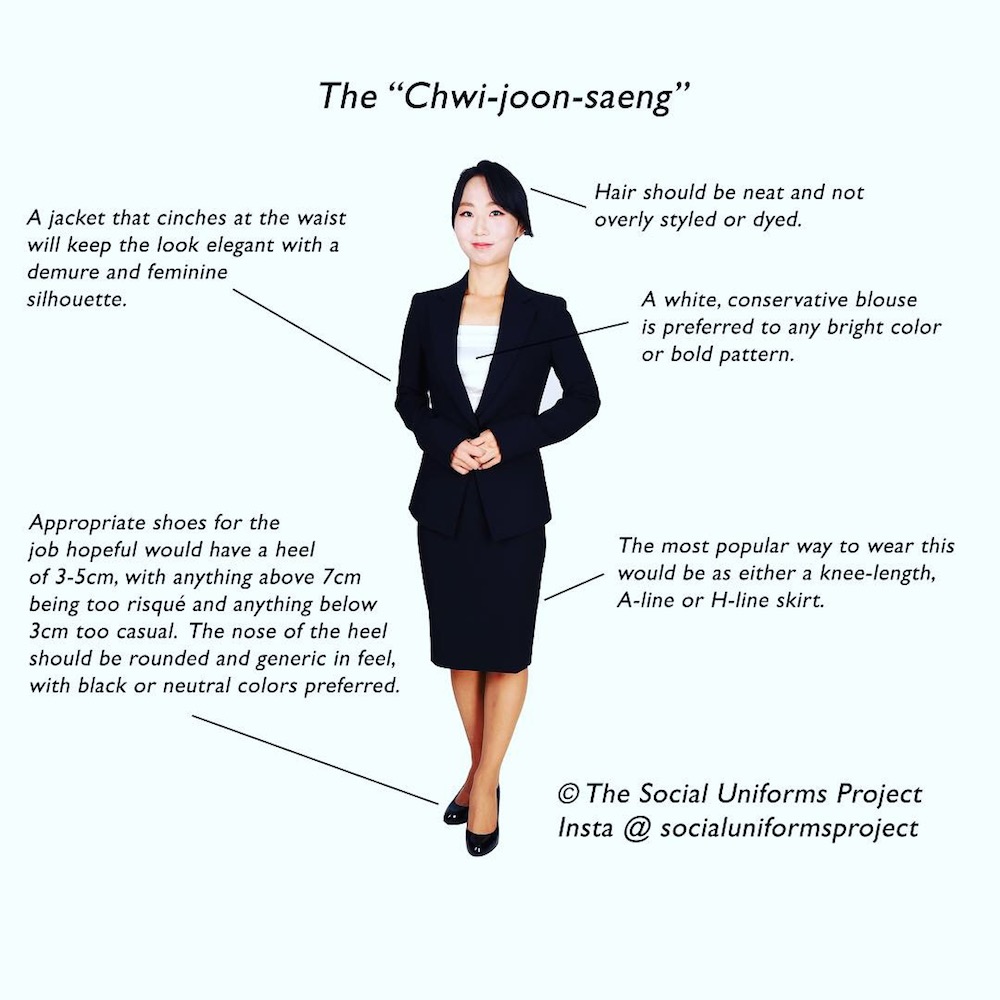

The Social Uniforms Project, write its creators in a recent Korea Times piece, “visually recreates moments/characters we see in Korean society that everyone else knows are true,” channeling “social messages through ‘social characters’ who wear certain kinds of ‘social uniforms’ that are quite recognizable in Korean society.” Its photographs document “the various manifestations that femininity takes, in their visible and socially performed ways,” revealing the “the social norms and rules that govern the way many individual women embody the social programming that says women should comport themselves in specific ways.” Some of these women are common figures in Korean life — “teacher, student, office worker, young mom, new bride on her wedding day, fashionista” — and others less so: “the chwi-joon-saeng fresh grad trying to get that first job, or the college super-senior on graduation pics day at a women’s university.”

None of these figures are androgynous on any level, least of all the one who wears “the Holy Grail of the female social and actual uniform,” the Korean Airlines stewardess, standing as she does at “the pinnacle of modern, Korean femininity and gender performance. That uniform is power.” Given that The Social Uniforms Project has only just begun, its creators have yet to attain that particular Holy Grail, but model Baek Min-a — the same model in all the account’s photos, dramatically transformed with each change of setting — has apparently learned a great deal from the uniforms she’s tried on so far. “Even though I play different roles, there is a socially constructed gender norm applied to every character,” she writes. “And to varying degrees, it is highly conscious of the male gaze. We constantly check our mirrors after a meal to see whether our lipstick is smudged or not. Women’s work attire focuses more on enhancing the ‘feminine figure’ than practicality. In all walks of life, women are expected to act and dress in a way that is pleasing to the male’s eyes.”

Americans who have passed through academia in recent decades — or those who spend time in the corners of the internet given to quasi-academic societal critique — will be familiar with this sort of language. But then, the concept of gender as a social construct has gained a surprising traction in the wider public sphere lately, not least because of the fuel its enormous field of possible interpretations provides for prolonged and emotionally charged arguments. Some Americans who visit Korea instinctively recoil at what they see as Korean women slavishly presenting themselves to appeal to the “male gaze,” and what’s worse, often in ways too adherent to traditional roles and not expressive enough of their own individuality. (“People all dress the same here” sits on the common end of the long spectrum of Westerner-in-Korea complaints.)

For my part, the longer I live in Seoul, the more I admire the care and attention most everyone around me has obviously put into their appearance — both women and men. (I would be remiss, however, if I didn’t acknowledge the nontrivial number of Korean men who seem to put no attention at all into what they wear. In that regard, Tokyo puts Seoul, let alone any American city, to shame.) There are plenty of aspects of America I enjoy, but the slovenliness isn’t one of them, and I can’t quite say that I long for the androgyny either. Yet the observation of gender as performance potentially carries real insight, and I’ve found no better frame for it than one put forth by a Twitter philosopher by the name of Zero HP Lovecraft, in a thread on how ideas only disseminate when stripped of nuance and forced into universality that I happened upon not long before hearing of The Social Uniforms Project.

“Gender and sex are a feedback loop between social performance and biological tendency,” Zero HP Lovecraft writes. “Masculine and feminine archetypes are not all good, but the good ones are aspirational, and require work on the part of a man or woman to achieve them. Gender IS performative but rather than being an excuse to reject it, this is grounds to strive towards it, to perfect it, for a man to become an idealized man, and a woman to become an idealized woman, the consummation of their biology, rather than the negation.” Many a foreign observer has remarked on the shamelessly aspirational nature of modern Korean society as well as its tendency to contort itself over ideals, but fewer have said this: there is, for better or for worse, a whole lot of biology getting consummated here as well.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Ways of Seeing Korean Plastic Surgery

How the Seoul Government Turned a Bestselling Feminist Novel Into a Controversial PR Campaign

The Essential Korean Fashion Accessory of 2018: A London Review of Books Tote Bag

Capturing Seoul’s Street Style: Michael Hurt’s Fashion Photography

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.