Last month we featured the work of Seoul-based Korean-black American street photographer Michael Hurt here on the Korea Blog. But while those shots all capture something essential about the life of the city, most of them depict the Seoul of at least a decade ago — the equivalent, surely, of something like 25 years of change in Los Angeles. Since then, Hurt himself has also changed, going from pure street shots to a kind of hybrid of street and fashion photography, all part of a discipline of “visual sociology” that he continues to develop through his academic work. Since these two chapters of his career have produced such different images of Korea, I thought it best to give each its own post. When he posted the brand new series of shots of the subject above, I knew the time had come to put in work on this one.

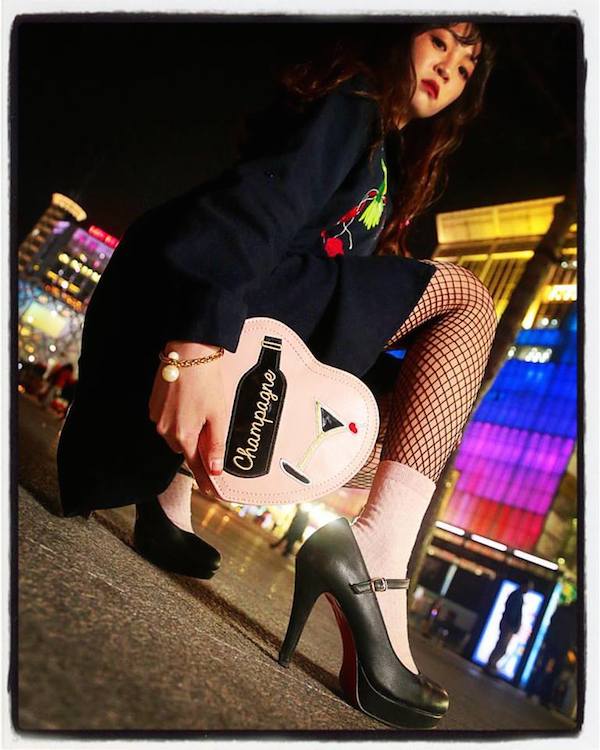

“This is a young lady I met on the last night of Seoul Fashion Week,” Hurt says. “To me, this kind of picture is the quintessence of Korean life and what one could call street fashion. One reason I connect very strongly with the real lies in the fact that, when it comes to representations of Korean reality outside of Korea, there is this strong Korean desire to dress up that reality to the point that it becomes nothing more than a superficial tourism commercial. People ask me whether these images are good or bad for people outside of Korea to see or whether I’m trying to advocate something such as smoking or sexiness or some other ridiculous thing.”

And what does he say in response? “The image I am recording, especially ones such as this one of the young lady smoking, are the most truly and socially real documentary photos that one could take. And in this post-1950s, reality television-reared, ‘I Want My MTV’ generation and its Photoshop- and YouTube-enhanced media environment, nobody wants carefully censored, government-curated, 1984 -esque tourism-bureau representations of reality. If those old fogies in suits could make Korea look cool with pictures of Korean traditional dress, dance, and flowers and other shit, Korea would’ve looked cool decades ago. And that’s why I love this fucking photo.”

Hurt explains more about his priorities in the essay “On the Inestimably Great Importance of Shooting Seoul ‘Street Fashion’ Slow and Proper”: “I came into this game as a photographer and academic doing street photography as social documentary, and then moved in the direction of documenting what women were wearing as a way of looking at changing gender role norms, the performance of gender in the Butlerian sense, and then at items of clothing specifically. So when I do what are essentially ‘environmental portraits’ that happen to take up sartorial concerns, I worry first about the background and then how that background is having a conversation with the subject. I worry about context first, the subject’s personality second, and the clothing last. And in the big picture, I am trying to capture something about Korean society beyond just the rags hanging on the subject’s body.”

In the shot above, we see “sartorial culture and trends and mediums bouncing across the decades and across the Pacific, not to mention between the high-fashion runway and the street. This is suku-jan, a Korean pronunciation of the Japanese word for Yokosuka, Japan” — a city bombed in retaliation for Pearl Harbor — “and jumper. It’s the hot ticket right now across the world’s collective street, and now that Korea is connected to the rest of the world and no longer dependent on local broadcast media to filter everything, it’s a good sign of just how far Korea has come with being connected in a global conversation, one in which Korean high-fashion runway designers are participating.”

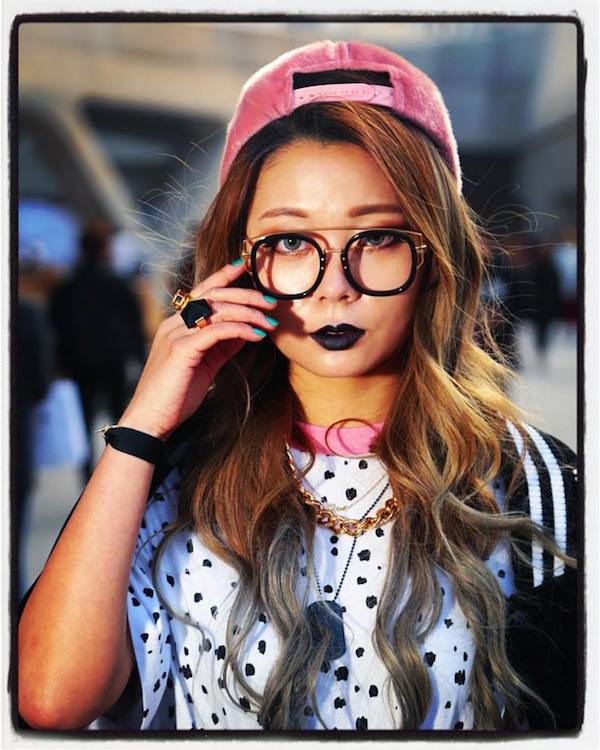

Here we have “the very picture of fast-changing gender norms in Korea, and a more open public culture of personal identity expression. What this picture is is a living, breathing, and vibrant repudiation of the old societal line that women are women and men are men, in terms of gender roles, and never shall the boundary be blurred.” The shot hints at a “multiplicity of friendship modes, sexual identities, gender performance and identities. It’s also a great and natural middle finger in the face of the oppressive heteronormativity of South Korean culture, and in that way is extremely refreshing. It’s one reason the folks at the Dongdaemun Design Plaza during Seoul Fashion Week, cool in terms of both the sartorial and social senses, are a pleasure to be around and help me cope with life in this culture.”

Hurt may find the heteronormativity of Korean society oppressive despite being heterosexual himself, but he also finds that, when it comes to capturing images of the boldest women’s style like the one just above, “my heterosexual male gaze enable me more than it cripples me. I’m not that concerned about the ‘fashion’ here, but the brashness of her outfit.” And that outfit “works in a very Korean way. It is veritably screaming SEX, SEX, SEX, but without doing it in the way an American sartorial message might, which would be to simply blare it out in a very literal way; the Korean way of dealing with sex is by stating its presence while also denying that’s what is being done. It maintains plausible social deniability.”

That means that “there’s not going to be any one, particular thing that gets a relatively mainstream, publicly reserved young lady like this in any pinpointable trouble,” especially one who understands that everything in her outfit “goes together in a Korean-edgy way, that it’s all cute and innocuous, even though it has a Hollywood-hooker aesthetic. No one is gonna say, ‘your socks are a bit Lolita‘ or ‘those heels are too high’ or ‘that bag makes you look cheap,’ because people aren’t working with these cultural messages that would actually get you in trouble in the FAR MORE SARTORIALLY CONSERVATIVE UNITED STATES. So I instinctively posed her in such a way that all the elements could come together and make the viewer GET what she’s doing without needing it spelled out too much.”

And as for the image projected by this Seoulite out and about, Hurt describes it as “simply cool, and it has that confident attitude so much more typical of young Koreans these days. She is also doing what many young women do: picking and choosing freely from available style options, which is why you see such a mix of seemingly dissonant elements, such and and girly, frilly pink dresses (which this young lady was wearing) and dark, emo-esque makeup, mixed in together UNIRONICALLY” — irony being, as I’ve written before, a resource in sometimes blessedly short supply around here — and in this frame in particular, “hipster glasses with a hip-hop-influenced, swagged-out, fuzzy pink hat.”

Hurt appreciated two things about the sensibility on display in this photo: “her youthful, beaming innocence and her jacket, which was on-trend and went with another huge fashion item, the white tennis skirt. Two birds, one stone.” And if those items strike you as oddly Western to have become so popular in Korea, I can assure you that you’re not alone. While walking the streets of Seoul, I every so often stop and think to myself, “Almost all of these thousands of people around me” — women, men, adults, children, the elderly — “are dressed just like Westerners.”

The thought sends my mind reeling, then casting around for an explanation, or at least some imagined image of what a modern Seoul in something other than Western dress would look like. But to Hurt’s mind, the very concept of “’Western’ style has no real meaning anymore, to the extent that even the Korean word for that, yangbok (양복), has come to simply mean a formal suit, as opposed to one half of a binary choice between Western versus Korean formal attire, hanbok (한복).” Interestingly, one does notice an increasing presence of hanbok-clad young women on the streets of Seoul today, though the sneakers they almost invariably wear beneath undercuts the effect somewhat.

“Certain aspects of Western fashion have become such universals that they’ve also lost meaning in an West-East binary. Take a pair of ten-centimeter stiletto heels, not uncommon on the streets of Seoul. Is that ‘Western?’ And especially since so many women wear six- to eight-centimeter heels all the time, even with hanbok, the distinction has become pointless. In the same way, I think few people in Korea see the automobile as ‘Western’ either, although it is indeed a Western invention — like the TV, the radio, or the telephone.”

In his recent essay and photo series “Spring Sogaeting with Cherry Blossoms”, Hurt probes further the question what street fashion photography can tell us about Korean culture. “And to take this line of thinking even further, what is even particularly Korean about Korean street fashion, if it’s not all particularly Korean material, patterns, or even brands?” When world-famous street style photographer Scott Schuman, better known as The Sartorialist, came to Korea, he captured not Korean style but “an increasingly global, non-culturally specific culture of dressing well, one that is enabled by global media outlets, the ubiquity of the Internet, and the homogenization of taste. What Schuman’s much fetéd visit to Korea actually meant to many Koreans concerned with his visit was how it marked a certain kind of recognition from the White West, that Korea — the Korean fashion field, actually — had achieved the much-coveted status of the truly Global that has been both a societal and state goal.”

Touching on such historical topics as Chinese suzerainty, the retaliation of and for Pearl Harbor, shifts in the dominant language of power, the divide between black and white U.S. servicemen, “neo-colonial Kool-Aid,” anti-communism, the 1988 Olympics, and the emergence of a “global fetish,” Hurt’s piece makes an attempt at explaining why “identifying the KOREA in Korean street fashion photography is increasingly problematic.” Where, he asks, “is the local in an entity whose popularity mostly comes from its globality? Where is the specific, the Koreanness, within an aesthetic system whose very logic and language is expressed in universal terms?” All this culminates in a series of photos, taken under the cherry blossoms now coming into view all across the country, of the kind of female self-presentation he describes, in its deliberate “social innocuousness, demureness, and sheer, unabashed femininity,” as “oh, so Korean.”

Still, some of the most fascinating aesthetic developments happening now go on not deep within cultural traditions, but along cultural borderlands. Before seeing that idea expressed in Hurt’s street style photography, I hadn’t thought to look for it in women’s clothes. I do follow a fair few publications to do with men’s style, an area in which Korea has only just begun to build up momentum. Many young Korean men still look dressed, directly or indirectly, by their girlfriends, and most of those who’ve attained a respectable age go in for drab, utilitarian looks — though strangely often with the accent of brightly colored athletic shoes. (I’ll probably have to keep going Japan for my menswear magazines for the foreseeable future.)

As ever in modern Korea, in stylistic as well as other respects, the women lead the way. (Quite a leap forward for a sex who, as recently as the turn of the 20th century, could barely leave the house.) If you want to see the future of this country, look to them, and not just to what they’ve put on today. “It’s not just about the clothing and who’s wearing it,” Hurt writes. “Because fashion isn’t just about clothing; fashion is part of a larger conversation, it is a cultural text, it is about social norms and value, social structures, all in the big picture, defined as what we call culture. If you can’t see all that in a street fashion picture taken in Korea, something major is missing.” For more, have a look at his pages on Instagram and Flickr, as well as his site Deconstructing Korea, which also has a section on his students’ work in fashion sociology.

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.