Stuff Koreans Like, a short-lived imitator of the mid-2000s satirical blog Stuff White People Like, only took ten posts to get to travel essay books. “Usually set in foreign cities (mostly New York or Paris),” writes its author, “they feature soft-focus photographs of café facades and interiors, coupled with inane text with no depth or historic/sociological insight into the destination being essayed about, just a lot of ‘Ooh this café was so pretty and its espresso so delicious. Ooh here’s another pretty café and its hot chocolate was so sweet.’” A tough assessment, but in its way a fair one: I come across dozens of (admittedly always well-designed) volumes that more or less fit that description whenever I browse the filled-to-bursting travel shelves at any of the bookstores here in Seoul.

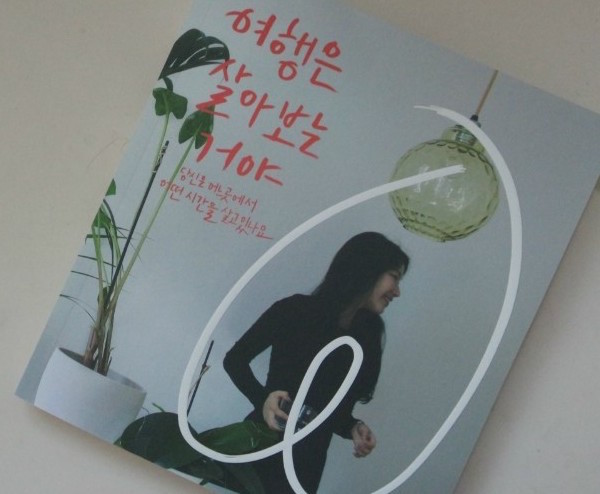

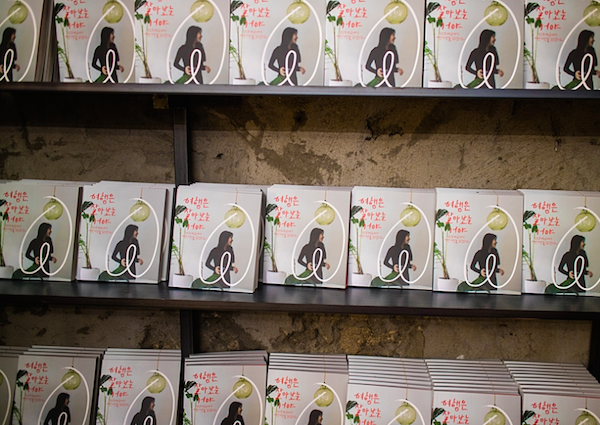

The popularity of the Korean travel essay book is not lost on Airbnb, the hugely successful and rapidly expanding service that matches travelers in need of a place to stay with possessors of houses, apartments, spare bedrooms, or couches looking to rent them out. Not long ago, I noticed that piles of a paperback called 여행은 살아보는 거야, or Travel Is Living, had appeared on the counters of several of my usual Seoul coffee shops. At first glance, its production value seemed high enough — comparable to those carefully laid-out, photo-intensive travel books — that I assumed they were for sale. Then I realized that I could simply take one like I could take one of the cinema schedules or festival fliers stacked beside them, and soon after that, when I’d read a bit, I realized that I held in my hands a 200-page advertisement for Airbnb.

Not that Airbnb needs to convince me of their merits: over the past five years, I’ve used the site to book accommodations all over the United States, Europe, and Asia, including on my first trip to Korea. They’ve surely got their fair share of free advertising from me in the form of recommendations made to friends, or at least to friends on the young side: what I think of as an “Airbnb generation gap” seems to separate those less to use it (as guests rather than hosts, at least) from those more to use it, just as it once separated the venture capitalists more willing to fund it from those less willing to fund it. But Korea, where even grandma and grandpa show up in line for the latest-model smartphone, has less of a problem there.

Travel culture has also, like much else in this country, grown with a vengeance over the past couple of decades. Koreans couldn’t travel freely overseas as tourists until 1989, when their still-newly democratic government finally relaxed the restrictions put in place to limit capital flight and brain drain during the postwar developmentalist decades. Before that time, almost every just-married couple’s honeymoon took them to Jeju Island, Korea’s equivalent of Hawaii or Okinawa an hour’s flight from Seoul. But unlike most everything else enjoyed by Koreans in previous eras, societal change hasn’t rendered that destination an entirely unfashionable. It even appears in Travel Is Living, written up by a young Instagrammer named Lee Ja-yeon who went there on a Korean-generation-gap-spanning trip with her mom.

The experience, alas, quickly devolves into an emotional standoff between the bored, island village-raised mother and sullen, uncontrollably weeping daughter, each keeping to their own parts of their Airbnb-rented house. But all of a sudden their host, who also happens to run a local chicken-and-beer joint, brings by some of his best merchandise for the ladies’ dinner on Jeju, thus saving not just the day but the entire vacation. A fair few of these good-luck stories appear in this book — or brochure, ad, branded #content, work of adutainment, call it what you like — which collects short essays on travel experiences commissioned from actual Korean Airbnb users, mostly women, all seemingly young and without exception Instagrammers.

If anything has become more popular among Korea’s younger generations than travel, it’s Instagram, the medium of choice for documenting one’s journeys abroad, nights out, art projects, reading material, meals, or even just cups of coffee: to put on display, to use the Korean mot juste, how one uses one’s yeoyu (여우). The words that don’t quite translate tell you the most about another culture, and yeoyu, which means something like a margin of comfort, of time or money or attention or anything else, points to exactly what Koreans, as their country rebuilt its economy from the 1950s up through the 1990s (when the Asian Financial Crisis took a chunk out of it again), did not have; school, work, family and society at large claimed everything.

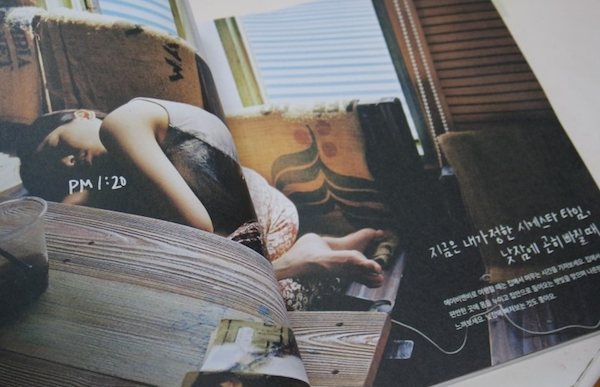

That condition still holds, to an extent, for young Koreans today, though they at least have a pressure valve in their ability to travel to other countries, countries that allow them the yeoyu — according to the series of introductory two-page photo spreads in Travel Is Living — to linger over a Western breakfast of coffee, bread, and jam; to browse farmer’s markets; to read a book in an easy chair; even to fall asleep on the couch in the middle of the afternoon. This ultra-leisurely lifestyle actually constitutes an integral part of life in the West in the Korean imagination, to the point where Koreans themselves now regard it as a cliché to speak of the “life” (삶) that goes on in other countries as against the mere “routine” (생활) back home.

I read my own copy of Travel Is Living, which I picked up at the appropriately named café Traveler (여행자), on a flight back from an Airbnb trip of my own. I’d gone to Fukuoka, the closest major city in Japan to Korea, and thus a popular destination for Koreans, so much so that the Japanese host of my Airbnb had communicated in Korean. Fukuoka appears in the book as the subject of an essay by a young Instagrammer named Lee Jeong-hee, who writes about the elegant meals she could prepare for herself with all the ingredients available there. Other contributors tell of their time spent in the picturesque Japanese cities of Kyoto and Kamakura, farther afield, in the picturesque European cities like Paris, Berlin, Lisbon, Athens, Helsinki, Copenhagen, and Tallinn.

Apart from Europe, Iceland also seems like a big draw: the book contains not just an essay about Reykjavík (a capital whose dominance of its country must feel familiar to Seoulites), but the second city of Akureyri as well. Other destinations featured in Travel Is Living, like Sydney or Airbnb’s home of San Francisco (no reports from Los Angeles, but chances are any given Korean has relatives there with whom they can stay for free), will look more familiar to the current generation of traveling Koreans, many of whom have already spent months or even years at a time in such places as international students or on “working holidays.”

Despite their late start, Koreans — at least those who don’t go in for the package-tour herding that seems to do such a good business here — thus have a great advantage in 21st-century travel. Unlike Americans, proportionally far fewer of whom take advantage of opportunities to study or work in other countries, they’ve already internalized the concept of traveling as a way of actually living elsewhere, developing as much of a lifestyle (including, by necessity, that ill-spoken-of “routine”) as possible, picking up as much of the language as possible, and interacting with the locals as much as possible, rather than burning their ten days’ vacation checking into a hotel, eating at the top ten restaurants, checking off the sightseeing boxes, and going home. Even if they have less yeoyu on the whole than their American peers, young Koreans tend to use it effectively.

Ironically, travelers to South Korea might soon start finding it difficult to do so with Airbnb, which has spoken of de-listing most of its available spaces there. “Airbnb will start deleting hosts who have not reported to the central and local governments that they are operating lodging businesses for foreigners,” writes Forbes‘ Elaine Ramirez, and “some 70% of listings are not registered with the government, according to local reports citing data from the Tourism Ministry. It is also illegal to convert ‘officetels,’ or studios in high-rise buildings designated for office and residence, into lodging, and those make up a heaping number of listings around the ever-popular Gangnam Station in the capital Seoul.” On top of that, “hosting an entire home for a tourist is illegal as regulators require hosts to be living in the same accommodation — in the name of promoting an environment for foreigners to learn about Korean culture through homestays.”

It makes sense, then, that Airbnb would double down on improving its image in South Korea overall, no doubt in hopes of avoiding the fate of Uber. No sooner did that other San Francisco-based pillar of the “sharing economy” tried to make its way into this country than it ran afoul of the taxi unions, giving time for Kakao, makers of the nearly universally-used Korean chat app Kakaotalk, to create and popularize their own service, called Kakao Taxi, instead. The proliferation of homegrown equivalents of foreign-developed apps has many a precedent in Korea, but Airbnb, which by its very nature needs a broad international user base, is in a different situation. But it has on its side two forces anyone underestimates at their peril: the new Korean zeal for travel, and the much deeper-rooted Korean zeal for making a few extra won on the side.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Coffee Life in Korea

Why Korea Needs Alain de Botton (and Why Alain de Botton needs Korea)

Finding Korea in Osaka

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.