The Sunday funny pages may now seem, even by current print standards, like the blandest, most marginal cultural forum imaginable, but they’ll always feature prominently in my own life story as the place I learned to read. Each week, I’d go from the basic, often slapsticky, sometimes entirely nonlinguistic humor of Garfield to the more artistically, emotionally, and verbally advanced likes of Peanuts to — if I could put in the time — the forbidding heights of Doonesbury and Zippy, with their detailed images and wordy mixtures of irony and earnestness, or the often mystifying, rarely attempted “serious” comics like Mary Worth and Apartment 3-G. Each week, I grasped a little more of their stories, their messages, their jokes.

In adulthood, I’ve come around to rediscover the delight of learning to read English in learning foreign languages. It has something to do with the immediate and perceptible (or at least theoretically immediate and perceptible) return on effort: learn a little more of a language, and you can then and there have that much more of a conversation, watch that much more of a movie, read that much more of a book, navigate that much more of a new environment. Since we learn our native languages in some sense unconsciously, without much in the way of deliberate effort, I didn’t get any particular charge — not that I remember, anyway — from learning to speak English. But later, when I opened up the comics each and every Sunday while learning to read English, a deliberate project indeed, I could feel both the rich satisfaction of making progress and the equally rich frustration of sometimes making less progress than I’d expected to.

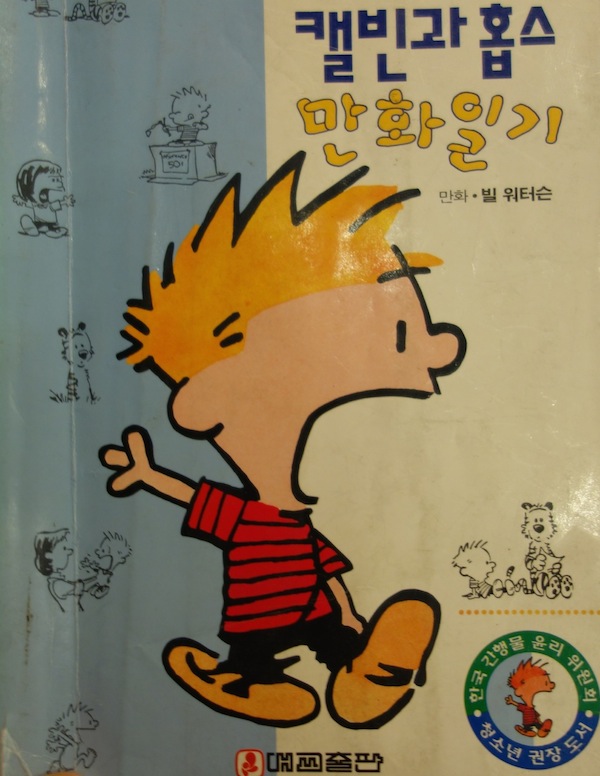

And so it’s gone with the work of mastering Korean, though since I live in Korea, the evaluation comes not once a week but every day, unavoidably, over and over again. Still, it occurred to me somewhere along the way that I could again use comics as a learning tool much as I used them over a quarter-century ago. On my first visit to Seoul, having come across a bursting-at-the-seams basement secondhand bookstore not only still open at almost midnight but manned by an eccentric owner who served us instant coffee (all of which, by itself, probably sold me on Korea as a place to live), I had good reason to snap up the book of Calvin and Hobbes strips translated into Korean I found wedged into the middle of one of the countless floor-to-ceiling piles.

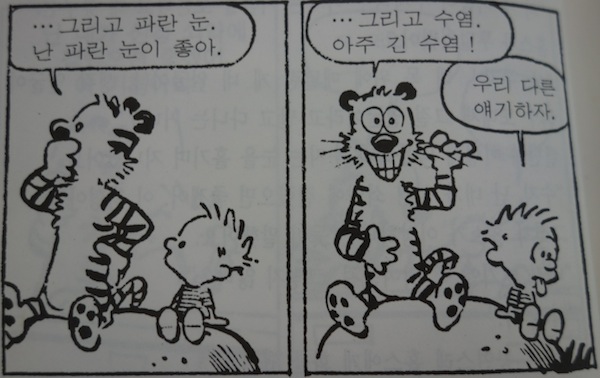

Calvin and Hobbes, unquestionably my favorite strip in the newspaper, always stood way out from the rest of the page. But I doubt I need to sell anyone, especially any American of my own generation, on the merits of Bill Watterson’s game-raising vision of an imaginative six-year-old boy and his tiger, which ran from 1985 to 1995; I understand there even exists a documentary consisting, in large part, of my fellow Millennials talking about how much the strip meant to them. As time goes by, I’ve found ever more to appreciate in this possibly last great newspaper strip, though back before I’d even reached its protagonist’s age, I sensed that I also had much to learn from it, linguistically and otherwise.

Before long, my reading skills reached the point where I could spend hours with the Calvin and Hobbes collections I put on every birthday and Christmas list, pausing only occasionally to look up Calvin’s more incongruously advanced words or cultural references. “Calvin’s vocabulary puzzles some readers,” his creator once wrote, “but Calvin has never been a literal six-year-old.” (“Besides,” he added, “I like Calvin’s ability to precisely articulate stupid ideas.”) I eventually got the idea that, if I followed Calvin’s example in that respect, I could gin up the illusion of intelligence in the company of other kids and grown-ups alike. I don’t recommend that strategy; having successfully faked my way into the role of Smart Kid, I spent the rest of childhood and adolescence avoiding any task, intellectual or otherwise, difficult enough to potentially strip me of the title.

Figuring my patchy Korean vocabulary could use a touch of the incongruously advanced, I opened this Calvin and Hobbes Comic Reader (캘빈과 홉스 만화 일기), a collection of strips translated into Korean and published in 1994 as part of a series geared toward young students. Though it came out late in the life of Calvin and Hobbes itself, the book includes mostly early episodes from the first few years of its run, few of them based on preposterously elaborate rhetoric, many based on simple mischief: Calvin playing the cymbals in bed; Calvin left alone for the evening and immediately ordering forbidden pizza and watching forbidden horror movies; Calvin trying to shorten his bath time by sitting inside the toilet bowl, flushing, and spinning round and round.

In one strip, Calvin, always keen to earn a nickel, asks his mom for an advance in his allowance, whether any outstanding war bonds might bear his name, and so on. Coming up dry on every count, he finally asks whether he could have some soap, to which his mom replies that he can have as much as he wants. In the last panel, we see him sitting outside, at a folding table beside the family car, on whose windshield he has written — in soap — “4 SALE CHEEP!” Or that’s what we see in the original American strip, anyway; the Korean one inexplicably changes the words to “SOAP FOR SALE.”

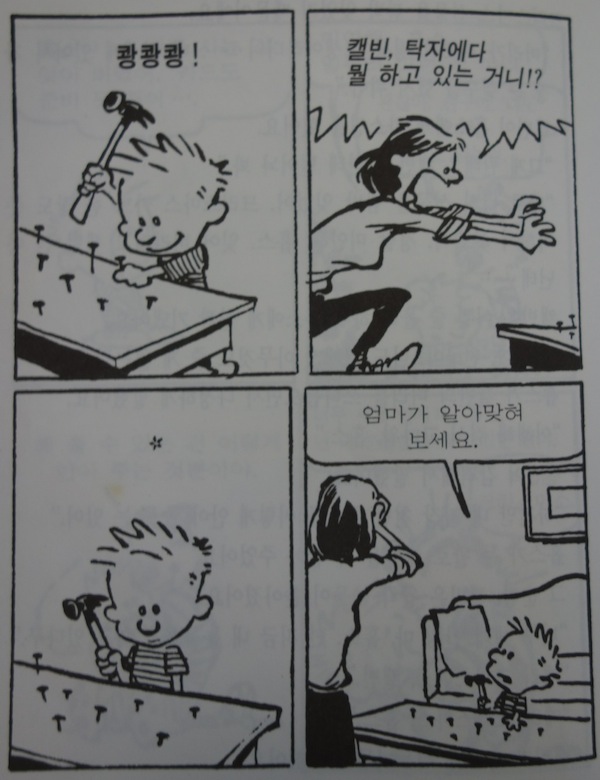

To the Korean-learning Calvin and Hobbes fan — especially to one like me, who spent a sizable chunk of his formative years reading and re-reading, and thus inadvertently committing to memory, the original strips — these alterations of content at once disappoint and fascinate. Sometimes they come from the translator’s apparent misunderstanding of the source of humor in the original, as in the Korean version of a particular favorite of mine, the one where we first see Calvin happily hammering nails into the coffee table; then Calvin’s screaming mom, rushing over to ask what he’s doing; then Calvin, after a moment of blank reflection at his handiwork, asking, “Is this some sort of a trick question or what?” In Korean, he just says, “Guess, mom” (“엄마가 알아맞혀 보세요”).

Stranger still, on the facing page from each strip in the Calvin and Hobbes Comic Reader appear a few explanatory paragraphs, not just retelling the story of the strip across from it but making up framing events before and after it as well, all purely speculative and well outside Calvin and Hobbes canon. The text for the coffee-table episode even describes Calvin as diligently hammering the nails in the shape of the Big Dipper. Several of the strips about Calvin’s never-ending campaign to gross out Susie, his classmate as well as the girl next door, become, in their accompanying texts, chapters in the saga of Calvin’s heart-pounding crush on her. (One of them has Calvin coming home full of shame, confessing to Hobbes his remorse over having lied to Susie at lunchtime, telling her his sandwich was full of squid eyeballs.)

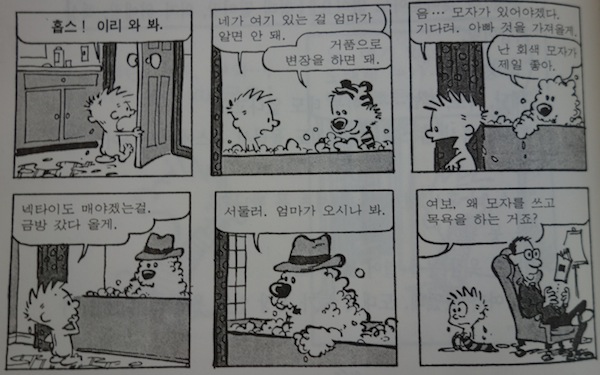

The rubber duck in Calvin’s bath turns to wood (though he still uses it to test for the presence of sharks, a practice that puts the Korean Hobbes on the verge of tears), and his red wagon, vehicle of so many careening philosophical discussions, becomes a “toy car” (장난감 자동차). A variety of unexpected pop-culture references also make their way in through the supplementary prose, from MacGyver to Jurassic Park. (Watterson himself deliberately stopped including dinosaurs in the strip for a time after the theatrical release of Steven Spielberg’s CGI-dinosaur extravaganza, not wanting to subject the images of Calvin’s imagination to the comparison.)

The question of why the Korean version of an American comic would work in even more mentions of things American could consume a whole other post, but at least they work in the sense that neither the translation of the dialogue nor all this newly written material relocate Calvin and Hobbes to Korea. They do, however, make the occasional connection to Korean culture, as when Hobbes tells Calvin, who’s just received a pack of cigarettes from his mom (who intends Calvin’s inevitable nauseous coughing fit as a lesson), that tigers used so smoke in old-time Korea — or at least he’s seen his probable Korean cousin Hodori, the 1988 Summer Olympics’ friendly tiger mascot, doing it.

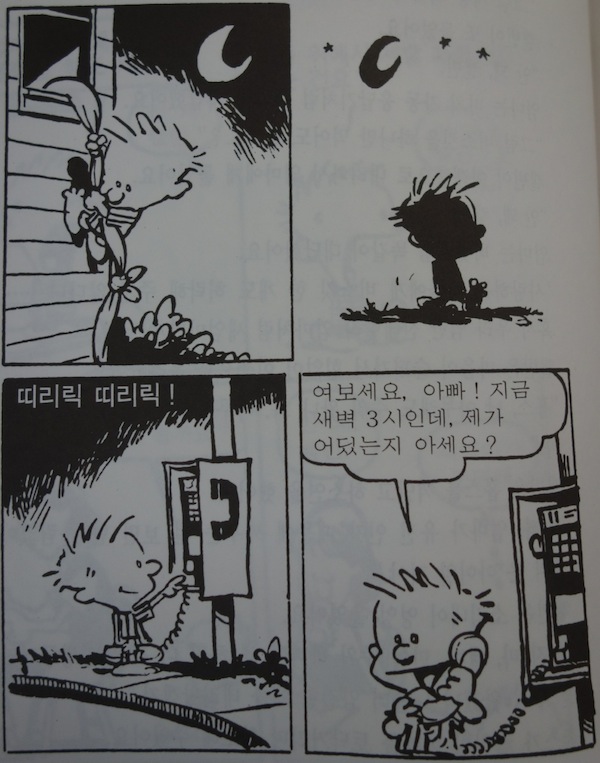

Some things, of course, never would have translated smoothly. When I first read the strip where Calvin wakes up in the middle of the night, climbs out his bedroom window and calls his dad on the payphone across the street to ask, “It’s 3:00 a.m. Do you know where I am?”, I found it funny enough, but it turned hilarious when I saw the long-running public service announcements Calvin was quoting. (The Korean text across from it turns his joke into a solemn test of fatherly compassion; Dad fails, leaving a devastated Calvin tearing up under the moonlight.) Yet try as I might to get the humor across to one Korean friend as I excitedly showed her this book, she could never quite identify what she was supposed to be laughing at. The subsequent hour during which I struggled to explain the “trees sneezing” strip, perhaps Calvin and Hobbes‘ finest hour (though it doesn’t appear in the Reader), met with more or less the same result. But the more beloved an work of art, the more you can benefit from examining it through another cultural lens — even a lens that kind of screws it up.

This particular interpretation of Calvin and Hobbes plays fast and loose enough to fumble much of what makes the strip compelling in the first place, such as Hobbes’ deliberately ambiguous existential state, suspended eternally between stuffed doll, imaginary friend, and conscious being; the introduction to the Reader flatly describes him as a toy that comes to life whenever only Calvin is around. But larger points remain intact: in Calvin and Hobbes, as the book’s afterword emphasizes to its Korean readers, “despite the different language and customs of this faraway country’s children’s story, you see yourself reflected.” And somewhere in there I see my much younger self, often not quite grasping the language, but nevertheless keeping at it, enjoying the process enough now not to worry too much about a payoff later.

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook. If you’re in town, come to the free, bilingual Seoul Book and Culture Club event he’ll host on Saturday, April 2nd, a conversation with award-winning young Korean writers Kim Ae-ran, Chan Kangmyoung, and Kim Min-jung.