On the day we caught Okja, the latest, Netflix-produced film by superstar Korean director Bong Joon-ho, my girlfriend and I went to a tonkatsu place we’d been meaning to return to — deliberately eating before the screening, not after. Everything we knew about the movie, posters for which went up in our neighborhood in Seoul months before it opened, suggested that we’d leave the theater after this tale of a girl and her giant, genetically enhanced pig with our desire for pork greatly diminished. Still, anyone familiar with Korea has to suspect that no movie, no matter how heartwarming, could take much of a bite out of this heartily carnivorous country’s formidable meat consumption.

Reports have it, though, that both Bong and Okja‘s young star Ahn Seo-hyun went vegetarian during production. At least they did during the shooting of the film’s final scenes set in a vast slaughterhouse for giant pigs, or rather Superpigs, that being the trade name under which the film’s evil corporation plans to market the titular Okja and her cheap, delicious brethren. The story opens in 2007, with that evil corporation — Mirando, certainly not to be confused with any other three-syllable multinational agricultural-product concern beginning with M — announcing a contest: having fortuitously discovered the Superpig, they’ve sent trial Superpiglets to every corner of the Earth, and in 10 years’ time will check back to see which country has managed to raise the biggest and most robust specimen, the key to solving humanity’s looming food crisis.

Korea-studies academics have already begun their field day over the culturally telling aspects of the film, beginning with how it treats almost as a foregone conclusion that the most impressive of the Superpigs would come from the Korean countryside. There, up on a mountain, lives 14-year-old Mija, her farmer grandfather, and Okja, who weighs seven tons and whose porcine features look hybridized with those of a dog and a hippopotamus. But their rural idyll shatters on the day, a decade after the first scene, when the Americans from Mirando huff, puff, and sweat their way up the steep trail to the family home (clearly no such challenge to the hardy septuagenarian in residence and his young charge).

The Americans have come to grant Okja the status of the world’s best Superpig, and therefore to reclaim her as a marketing tool for Superpig meat. One of them, a drunken nature-show host called Dr. Johnny Wilcox, expresses surprise when Mija asks for his autograph: “I guess I’m still hip in Korea,” he says in one of the few subdued moments of a manic Jake Gyllenhaal performance New Yorker critic Anthony Lane calls “barely watchable.” If that sounds harsh, Lane’s choice of the word “spirited” to describe Tilda Swinton, playing the CEO of Mirando (as well as her twin sister), carries the whiff of euphemism. For all its the ground it breaks for cross-cultural cinema, Okja falls victim to what I call My Blueberry Nights syndrome, the tendency of skilled Western actors to give inexplicably awkward performances — stiff or bombastic at best, Gyllenhaal-as-Wilcox at worst — in films by respected Asian directors.

I think back to the words of Josh Stolberg, who played a caricature of an unsympathetic white boyfriend in Western Avenue, the Korean film about the 1992 Los Angeles riots: “I remember the director really pushing for ‘more emotion.’ They didn’t want anything ‘internal.’” Wong Kar-wai fell victim to this before Bong, as did Iwai Shunji and Bong’s countryman Park Chan-wook in their fascinating but oddly detached pictures Vampire and Stoker, set in Vancouver and Connecticut, respectively. When the inventive, genre-hopping Kim Jee-woon went to Hollywood, he wound up in the director’s chair of The Last Stand, an Arnold Schwarzenegger and Johnny Knoxville movie about a car that goes real fast.

But Bong himself has more experience: Okja actually marks his second cinematic foray into the West, the first being 2013’s mostly English-language sci-fi thriller Snowpiercer, which also starred an equally spirited Swinton. Each of his four all-Korean features before it had, to one extent or another, a satirical bent: his debut Barking Dogs Never Bite (플란다스의 개) took as material the dynamics of Seoul’s vertical communities and its ostentatious dog-owning culture (as well as its marginal dog-eating culture), and The Host (괴물) built a highly entertaining monster movie, by turns silly and serious, on the recurrent suspicions Koreans harbor about what recklessness the American military might be getting up to in their country (despite how many of them would, at the same time, never dream of letting the U.S. quit Korea entirely).

Okja incorporates the complicated relationship between the United States and Korea into not just its substance but its form, which follows its rural-Korea segment with one set in the capital before crossing the ocean to New York and coming back again. Determined to free her best friend from Mirando’s clutches, Mija finds her way to their Seoul office where Okja is already being prepared for shipment back to corporate headquarters. A chase (its pathway through Seoul’s streets both above and below the ground a reminder of Bong’s skill with the city seen in The Host) ensues, involving not just Mija and Okja’s captors but a third party: a cell of the Animal Liberation Front intent on exposing the genetically-engineered origins of the Superpig and the species’ abusive treatment at Mirando’s hands.

Both of the film’s best Westerner performances come from actors portraying ALF members: Paul Dano as Jay, the cell’s eloquent, strictly principled leader, and Steven Yeun as K, the Korean-American there to translate. Yeun, best known from the zombie show The Walking Dead but also seen as Conan’s O’Brien’s inept cultural liaison on the late-night host’s visit to Korea, plays a type seen fairly often in this country: the Western-born or Western-raised Korean pressed into the kinds of interpretative service for which nothing has properly prepared them. K’s poor pronunciation and simplistic grammar in Korean will get a few cheap laughs from viewers with knowledge of both languages, as will his hasty distillation of J’s miniature monologues into three or four syllables.

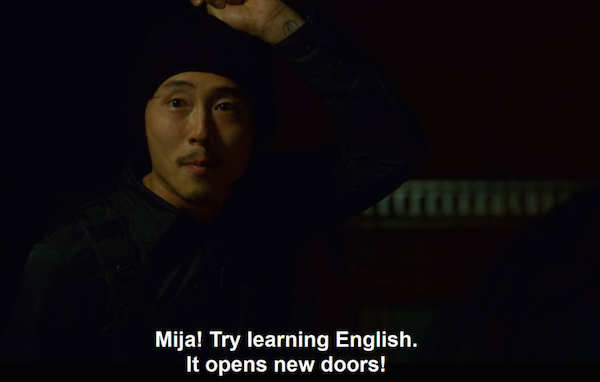

But not all of K’s mistranslations happen by mistake: when Mija’s objects to the ALF’s plan to implant Okja with a hidden camera and let Mirando recapture her, K simply fabricates her agreement. This later results in a savage beating from Jay and a penitential tattoo reading “Translations are sacred,” but before that comes what some outlets have called Okja‘s best joke, and one accessible only to those familiar with Korean language and culture. The members of the cell escape one-by-one from their speeding truck, leaping over the side of an expressway into the Han River that bisects Seoul (and from which emerged the city-terrorizing monstrosity of The Host). Just before making his jump, K turns to Mija and imparts a few last words to her in Korean: “My name is Koo Soon-bum.”

The fact that K has a Korean name won’t strike many English-speaking viewers as notable, not that most of them will ever know he said it: the film’s English subtitles “translate” that line as, “Try learning English. It opens new doors!” (Having seen a fair few English-language movies here in Korea, I can assure you that Korean subtitles, too, suffer from a certain humor impairment.) Many Koreans have heard the same thing over and over from their country’s English-language industry — speaking of corporate evil — but they’d get more amusement from the comically old-fashioned and unsophisticated sound of “Koo Soon-bum” itself. “That’s a dumb name,” as Yeun straightforwardly explains it.

Many in this country, where grown adults routinely exchange their given names for those that happen to be popular popular among the young, might consider “Mija” and “Okja” equally “dumb.” Or at least they’d consider them equally outdated, ending as they do in a syllable that pegs them right to the generation of Korean women born in the 1930s and ’40s; imagine, if you will, a CGI-heavy adventure film with protagonists named Betty and Phyllis. But the movie’s popularity (despite a boycott by Korea’s major theater chains who, pleading vulnerability to the power of a hulking American enterprise like Netflix, didn’t want to get in the habit of carrying anything streamable online at the same time) may herald a renaissance for humble -ja names and the down-home virtues one could see them as representing.

Okja‘s view of the Korean countryside, of its adherence to tradition and its relative insulation from the influence of the global economy, brings to mind Shinkai Makoto’s Your Name, a tale of body-switching between urban and rural teenagers that earlier this year became the most successful Japanese animated film of all time. “Tokyo’s skyline beckons like a 21st-century Emerald City, but the countryside, too, brims with vitality, both natural and human — its forests unspoiled, its schools filled with students, its festivals thronged with visitors,” writes Japan observer Matt Alt in the New Yorker. “The movie is an elegiac meditation on a Japan that no longer exists — if it ever truly did.” Still, after the inward turn resulting from the stalling of its highly-flying economy in 1990s and 2000s, Japan has seen the beginnings of a back-to-the land movement.

Something similar one day happening in the more recently and more quickly developed Korea, led by a generation of Mijas or otherwise, isn’t completely impossible. Surely it stands a better chance than the abandonment of meat-eating, for which Okja makes the softest possible case. Along with the Superpig’s increased size comes, judging by the subtleties of Okja and Mija’s non-verbal relationship, an increased intelligence, possibly a riff on the standard vegetarian’s line, never especially convincing to those without similar leanings, about pigs being too smart to eat.

Alas, the concept of vegetarianism itself doesn’t seem to translate here: if I ask, on behalf of visiting vegetarian friends, for food with no meat, it will probably come out with fish. When I ask for food with no animals, it will out with fish cake. Not that Mija goes vegetarian either: that the film’s final scene finds her once again ensconced on the mountain with Okja and her grandfather, maker of an appetizing-looking (and classically Korean) fish stew, will come as no surprise to anyone aware of Bong’s Spielbergian sensibilities, confirmed by no less cinema-obsessive a colleague than Quentin Tarantino.

Bong and the director of E.T., Empire of the Sun, and A.I. Share, among other qualities, a penchant for using children to embody certain virtues. In Okja‘s case, the virtues are national: we see Mija the way Korea has long seen itself, as tiny, unfamiliar with the customs and codes of the wider world, and forced to cooperate with powerful and often heinous foreign entities, but also resourceful and wily enough to get her own way in the end. Audiences may well find themselves similarly unchanged by the viewing experience, back to urban life as usual and tucking into a tableful of grilled pork belly the very next day — or that’s what I found myself doing, at least.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Western Avenue: How Korean Cinema Portrayed the 1992 Los Angeles Riots

Blade Runner 2049 and Los Angeles’ Korean Future

Korea’s English Fever, or English Cancer?

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.