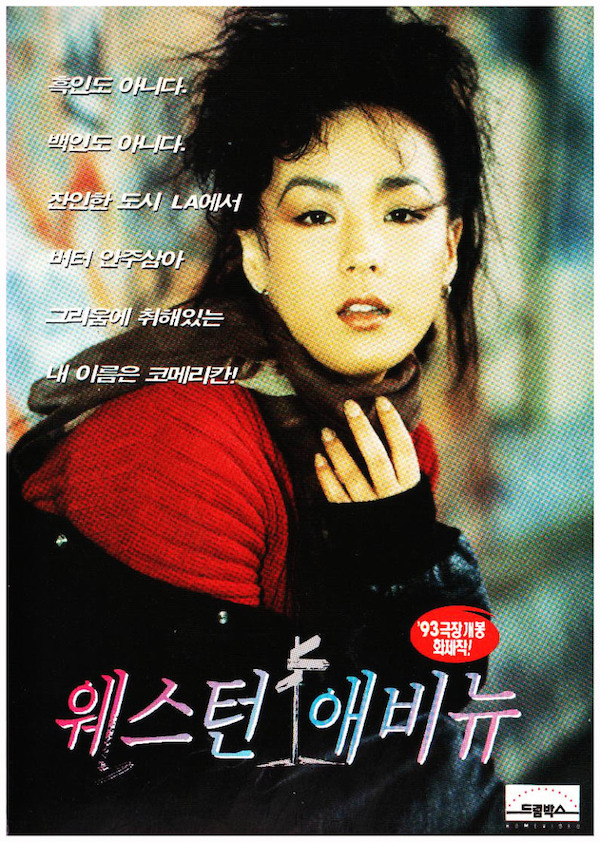

The Korean name of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, sa-i-gu (사이구), means “four, two, nine” — or rather 4/29, the first of the six days they tore through streets after the the Rodney King verdict came out. Given Los Angeles’ large Korean population, the highest of any city outside the Korean Peninsula itself, and the fact that its Korean-owned stores took so much of the damage, the Korean media granted this unrest on the other side of the Pacific the importance of a domestic disaster, flying at least 30 journalists straight over to interpret the chaos for the dismayed and bewildered audience back home. The very next year, Korean cinema, enjoying a 1990s resurgence after a couple decades spent losing out to foreign (and especially Hollywood) imports, came out with its first and still only statement on the riots: Western Avenue.

Directed by Chang Kil-soo, a filmmaker already known for telling stories of countrymen crushed in pursuit of the American Dream, the movie (which you can watch, albeit without subtitles, on Youtube) sees the riots through the eyes of a representative Korean immigrant family: Kim and his wife, who arrive in Los Angeles in the 1970s and work hard to save up for their own convenience store in which to work harder still, and their three Korean-American children, saddled with the “English names” of Frank, Bobby, and Marian. Just before the riots break out, the film carefully gathers the entire Kim family, along with the store’s sole black employee and his grown son, into their blast radius with only a single handgun for defense. But its last-act depiction of Korean suffering at the hands of black rioters comes after much more time spent depicting Koreans suffering at the hands of unsympathetic whites.

Or rather, its first two acts focus on the suffering of Marian — real name Jee-soo — after she dares to change her college major from medicine to drama, getting temporarily disowned by the enraged Kim as a result. Graduating from Yale, she moves to New York with her fledgling filmmaker boyfriend Steve, a mulleted loudmouth who takes her idea of making a movie about her own immigrant experience and turns it into an psycho-erotic spectacle titled The Exotic. “This film is so sexual,” asks a ponytailed slickster at its debut Q&A. “Did you have a hard time to act, with the Oriental morals?” Chang presents this as the humiliating nadir of Marian’s futile struggle for acceptance in the country she had since childhood regarded as her own. When she justified her disobedience of Kim’s demand that she become a doctor, she’d described herself as not a Korean but an American — only to have Steve describe her as “my little wildflower from the Orient.”

Western Avenue played only in Korea, and American viewers will quickly sense that the film was never intended for international consumption anyway, not least because of the sometimes unintelligible English of Kang Soo-youn, the big-name Korean actress playing the supposedly Westernized Marian, as well as the Korean-born actors in most of the other “Korean-American” roles. “On set, she struggled a bit with the English, but she was really working hard,” Josh Stolberg, who played Steve before becoming a writer and director in Hollywood, wrote to me in an email. “I’ve seen her in Korean films where she was able to speak in Korean and I think she’s AMAZING — but this was definitely tough.”

Though miscast, Kang nonetheless has several memorable turns of phrase throughout the movie, such as Marian’s comeback to the (also heavily accented) insistence from her older brother that she shouldn’t hang around actors and artists because “most of them are either homosexual or have some kind of mental problem.” “Yeah, I have mental problem,” she replies. “It’s my life!” She also offers a brutal criticism of Steve’s work: “Can I tell you frankly? Your script suck. Of all the thing I read, yours is worst.” This even before their final falling-out, a scene culminating in Steve’s bitter lament, “Why do you give up your Oriental ideals of submissiveness and male superiority?” Though Stolberg remembers Chang as “a lovely guy,” they did have their differences when it came to performance styles. “I remember shooting an intimate scene with [Kang], and I was playing it very subtle, and I remember the director really pushing for ‘more emotion.’”

“They didn’t want anything ‘internal,’” wrote Stolberg. “It was far more melodramatic (in terms of performance) than I was used to” — but very much the kind of tone Korean cinema and television drama has always made work, and in which its best creators have somehow even excelled. “I knew going in that I was playing a complete asshole. I was always pissed off and pompous and a jerk. It was completely over-the-top. That said, I was fine to play the part, partially because, having grown up watching movies where Asian actors were forced to play stereotypes, I felt fine about it being our turn. I was also young, though,” as well as excited about the opportunity the role represented and “awed by playing opposite one of Korea’s most well-known actresses.”

Realizing how Steve has used her, Marian plunges into a downward spiral, developing a drug habit (or rather, having white acquaintances foist it upon her), roaming the streets in a frizzy-haired daze, and blankly submitting to the advances of a Chinese artist-thug. Before long, her (also mulleted) younger brother turns up in the parody of American urban decadence into which she’s fallen to bring her back home to Los Angeles, where she reconciles with and starts working for her dad back at Kim’s Market on Western Avenue. The film places her homecoming around the same time as, and incorporates security-camera footage of, the real-life March 1991 shooting of black teenager Latasha Harlins by Korean convenience store proprietor Du Soon Ja. Her death would become not just a reference in many a subsequent Tupac song, but a factor often cited as precipitating the riots of the following month.

“I didn’t kill no Latasha!” insists Kim to a throng of black protesters chanting outside his store, but to no avail. Norman, the prison-radicalized son of Kim’s loyal black employee, has taken it upon himself to organize some of the protests. “We’re boycotting Korean stores because most Koreans are arrogant, they’re rude, they don’t talk to black people, they don’t laugh with black people, and they look down on us like we’re a piece of shit,” he complains to Marian, his onetime childhood playmate. “Not all Koreans are like that!” she replies, a statement that would now come with a hashtag. She argues that conflicts between blacks and Koreans in Los Angeles erupt due to mere cultural misunderstandings, while Norman says that’s all the more reason for Koreans to get with the American program, illustrating the city’s ongoing clash of incompatible norms taken on more recently (and much more over-reachingly) in Paul Haggis’ Crash.

“I did know, going in, that the film was supposed to be a statement on the riots from the Korean perspective,” wrote Stolberg. “And I was excited to be in the film because I was here in Los Angeles for the riots and it really affected all of us. So I wanted to help them tell their version of the story.” In their paper “How the L.A. Riots Was Remembered in Korean Cinema: Western Avenue and Shattered American Dreams,” Hallym University’s Park Seung Hyun and Kyungpook University’s Kim Yeonshik argue that, in telling that version of the story, the film “acknowledges the tension of the ‘black-Korean conflict’ surrounding shops that Korean Americans manage in black ghettos, but refuses to name this inter-ethnic conflict as the main cause of the riots. The film instead complies with a popular perspective argued by Korean Americans during and after the riots: Korean Americans were set up as the scapegoat of African Americans’ anger against deep-rooted racial discriminations in the United States.”

Park and Kim also clarify several aspects of the film’s perspective on the riots that wouldn’t necessarily be obvious to a non-Korean audience. “The upheaval in Los Angeles, the most favored city of Korean immigration in the land of new opportunity, was a watershed event for rethinking the life of Korean Americans in the United States,” they write. “This event eventually led Koreans to recognize that there was something deeply wrong with the American system,” specifically “an absence of social legislation and protection,” and this “shattered their faith in the American society and the American dream for which they had emigrated from their motherland.”

The film’s Kim and other Korean immigrants to America of the 1970s still regarded the United States as “the colonial liberator and Korean War savior,” a “prosperous and freedom-loving country” as opposed to their underdeveloped homeland “where authoritarianism was deeply woven into the fabric of everyday life.” The aspirational vision of America as a blank socioeconomic slate, “a place where individual labor and effort determine success and failure,” thus blinded the Korean immigrants of that era to their new country’s “long-standing racial problems,” even as they propagated various myths about the groups they’d never encountered in Korea. “My mom and dad tell me that your parents like black people!” says an aghast Korean-American classmate to a grade school-aged Marian in the film’s prelude. “My mom told me that if you touch black people or stuff they touch, you’ll turn black too!” (Implausible as it seems, Park and Kim call this “an undeniable stereotype that Koreans once held.”)

A quarter-century after the riots, America’s reputation as a place of racial strife has only spread, joined by reputations for substandard infrastructure and political disorder, while the rapidly developed South Korea, for all its own problems, looks stable and advanced by comparison. (Just a few years ago, there was a bestselling book here by the name of 우리가 아는 미국은 없다, or The America We Know Doesn’t Exist.) “Before she leave, she ask me why I bring her to America,” a despondent Kim says after Marian flies the Korean coop to try leading an “American” life. “Now, I ask myself same question.”

Many Korean immigrants of Kim’s generation find themselves in a promised land that inevitably falls short of their rigid expectations — with children raised there who often do the same — and unwilling or unable to return to their now-unrecognizable homeland. Still, few have had their pursuit of the American Dream turn out as badly as Kim’s, which Western Avenue, true to melodramatic form, turns into a near-Greek tragedy amid the roaring flames, shattered glass, and smoky skies of sa-i-gu. The 25-year retrospectives now appearing on these most destructive riots in American history show the surprising extent to which most of the afflicted areas have recovered, even on the Western Avenue of the movie’s title.

That nearly 30-mile-long street runs through, among other places, heavily damaged parts of what was then known as “South Central” and, further north, the west side of Koreatown, a neighborhood that also took its lumps but had a better defense in the form of Korean shopkeepers armed with much more than Kim’s little-used revolver. I happened to live in Koreatown myself for all of my most recent years in Los Angeles. For half of those those years I lived just off Western Avenue, which I often walked just a few blocks up to catch a movie at the local branch of the Korean CGV theater chain, each piece of Korean cinema I saw there preparing me for my own eventual move across the ocean.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Why I Left Los Angeles for Seoul

A Korean Travel Writer Reveals the Los Angeles Even Angelenos Don’t Know

Wangsimni, My Hometown: a Gangster (and a Filmmaker’s) Pledge of Devotion to Korea

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.