Quietly, even sneakily, Kim Mi-wol is becoming a must-read Korean author in translation. Clever readers may have noted a point that has been beaten to death on this blog: younger female writers are leading the charge in Korean literature’s overnight success. From my perspective this is a wonderful thing, but also, by its nature, a limited thing. Because most of these authors come from similar demographics and deal with similar themes (alienation, the quotidian oppression of women, etc.), there is a thematic similarity to their work.

(PAUSE BUTTON.) I am aware that, in some ways, pointing this out borders on ludicrous, as “mainstream” literature has long been the turreted redoubt of white, male, primarily middle-class writers (see “Sorry White Male Novelists, But Sexism in Publishing Is Still A Thing” in xojane) and thus any kind of inroads that non-male writers can make should be celebrated.

(RESUME PLAY.) … which is why this post celebrates the writing of Kim Mi-wol, who certainly works within the outlines of the current market for Korean translations, but also writes quiet, certainly despairing, vignettes that cross the notion of “genre” fiction (again, see xojane for a dismantling of how female writers are pushed into “chick-lit” or “tawdry domestic dramas”), no matter how forcefully publishing and marketing might try to pigeonhole them.

Currently, Kim has three works available in translation. One of the best is “Guide to a Seoul Cave.” Translated by the indefatigable Brother Anthony of Taizé, it tells the story of a young woman (though it takes a bit of time for that to become clear) living in a gosiwon, an extremely cramped and noisy form of Korean housing, and working as a guide in an artificial cave in Seoul, one that circles around so that visitors exit right next to where they entered entry. Visitors, the narrator notes, “seemed to be expecting that after passing through the cave they would come out somewhere new, somewhere different from where they had come in.”

But of course they don’t, and can’t; their caves define them, and Kim’s point is that all of us (and particularly her characters) live in a cave of some kind. The story makes this literal this in the forms of both the cave and the gosiwon, and makes it into a metaphor as well, in that each character has fashioned a personal cave in which they live. Whether that cave is a “private paradise” (as the story’s introduction suggests), an adaptation to a splintered world, or a bare-bones refuge from that splintered world is left up the reader. Several “cagey” subplots weave in and out of the story, each ending in a kind of surprise of dull shock and recognition. Kim’s writing is so evocative, and her characterization so universal, that the story will resonate with most readers.

Also available online is Kim’s “Plaza Hotel,” again ably translated by Brother Anthony, the story of a couple that vacations in plush hotels in Seoul. The Sheraton Walkerhill, the Lotte Hotel, the Shilla, the Millennium Hilton: anyone who has lived in the Korean capital will recognize those names and the overstuffed, expensive luxury they stand for. Kim examines the meaning of money and value across a lifetime and pretty clearly outlines the kind of “myeong-pum” culture (“luxury stuff”) that segregates coffee shops in Seoul by computer type: MacBook Airs at the window, Macbooks near the front, and so on until the poor drinker with the twenty-pound black Dell huddled at the back of the shop.

The story bounces back and forth between the past and present of a man who, smitten in college, attempted to get his then-girlfriend to stay at the Seoul Hotel with him and now, in the present, takes his wife there. Once the focus of his intense sexual longing, the hotel has now become a kind of moneyed retreat with “the perfect temperature, perfect humidity, perfect cleanliness, perfect service, a feeling of being perfectly pampered. Surely it’s because we like that feeling of perfection that we keep visiting hotels? Isn’t that the blessing of capitalism, to pay money and buy perfection?” Kim also includes a perfect little scene predicting the younger lovers’ future, one without real passion, going on to neatly describe that passionless state and ending with a scene of something like stasis: a man alive in the biological sense, but dead at his center.

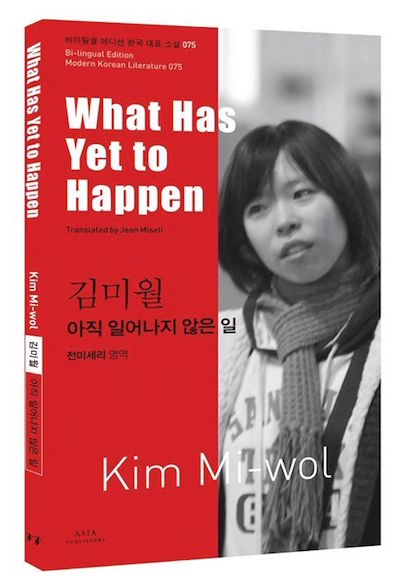

Finally, Asia Publishers have put out “What Has Yet to Happen” (translated by Jeon Miseli), Kim’s unusual and clever “end of the world” story without a Bruce Willis character to save the day, a spaceship to hop on and escape, or even much in the way of panic. The initial reaction of people in this book is to continue on in the path of their daily lives, as though today will lead to tomorrow, and tomorrow to the day after, and so on. The narrator’s most important initial thought is that she will not have to pay for her smartphone anymore, and life outside, while slightly changed — the bus is free, there is discussion of conspiracy, the narrator finally talks to her neighbor, soju is amusingly described as “a painless death” — just seems to go on.

This is Kim’s skill, as an extremely artful writer displaying a kind of day-to-day resignation to lack of meaning under which even the threat of extinction has no real impact. Kim’s uses real characters rather than exceptional ones, not whiners, both achievers and non-achievers, none of whom can find anything in their lives or society that gives either meaning. Underlying all this is the fact that Kim is also an amusing writer. The final scene of “What Has Yet to Happen” plays as a kind of an ironic joke, and the whole story is laced with humorous characters, whether snake oil-salesmen, delivery men, or bus drivers. There is even a set piece in which the narrator gets in a discussion about who is likely to be most upset over the world’s end. (One contender: the one who had planned to have their braces off the day after the world ends).

This “matter-of-fact,” super-light and funny writing style has the surprising effect of making a reader believe that the end of the world is, finally, “just another day.” And Kim brings this skill to all her work (all her work translated so far, I should say), capturing the general sense of alienation and disillusionment, as well as the unfortunate position of “lesser” people in Korean society with a witty and concise storytelling style that makes her work appropriate for most any reader.

Related Korea Blog posts:

The Triumph of Han Kang and the Rise of Women’s Writing in Korea

Bright Lies, Big City: Korean Authors and Seoul