In his review of the 2017 World Premiere production of Dan O’Brien’s The House in Scarsdale: A Memoir for the Stage (The Theatre @ Boston Court), which LARB also reviewed, critic Jonas Schwartz stated:

Dan O’Brien has written an American gothic tale on a par with Pulitzer Prize winner Sam Shepard’s best works. Like many of the characters in Shepard’s plays, the protagonist seeks the truth, but the answers will not assuage his guilt or pain.

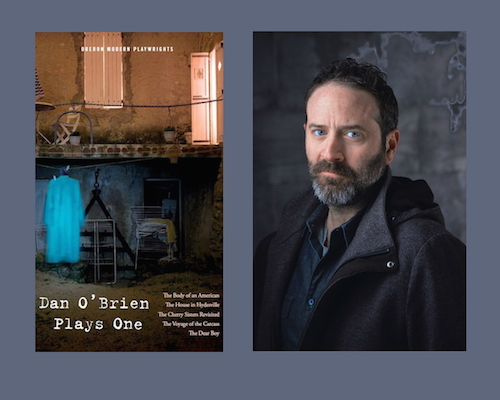

One need only devour O’Brien’s recently-released collection, Dan O’Brien: Plays One, a handsome and hefty volume of the prolific playwright and poet’s works (The Body of an American, The House in Hydesville, The Cherry Sisters Revisited, The Voyage of the Carcass, The Dear Boy) to glean the authenticity of Schwartz’s claim.

The late Shepard’s works were like haunted houses in the collective unconscious; an “Encyclopedia Psyche Americana” if you will. His characters, like the titles of his plays, were buried, and cursed, fools clinging to lies.

O’Brien’s plays are haunted houses too. Quite literally, in some cases. But these are like the houses where runaway teenagers seek solace; broken down, abandoned, skeletal remains of places where healthy, happy families once thrived. Hence, that aforementioned quest for truth begins in earnest.

While a sense of psychological placelessness often pervades O’Brien’s work, whatever gloom may fog over the proceedings is banished by the man’s poetry; his most recent plays are written completely and unerringly in 10-syllabic lines, but so natural is the speech that you’d never know this unless you were actually looking at the script.

I emailed with the playwright to have a few raps at his skull.

¤

TIM CUMMINGS: Looking at the way the most recent play in this volume is type-set, there’s structure here, a flow, vitality: the character headings on the left; the dialogue in a surge outward from there; no spaces in between, which relays an intimacy. On the far right, away from everything else, stage directions are gently suggested in italics, as if floating in their own world. How does the visual of the play on the page correlate to the way you write it, if at all? Are we looking at your mind?

DAN O’BRIEN: This was a new way of writing for me, beginning with The Body of an American, which you allude to above, through my next play, The House in Scarsdale: A Memoir for the Stage (which readers should know you performed so heroically this past spring in Pasadena), and my most recent play, New Life, a commission for Center Theatre Group in LA and currently in development. For years I wrote in so-called “standard format,” more or less the template provided by your average scriptwriting software. I’m not sure how and why my new style developed. It had something to do with a long cold winter in Wisconsin reading T. S. Eliot’s plays. It had a lot to do with being disowned by my family around that same time. My life was changing dramatically and drastically, so I knew my writing would too. I wanted to listen more to what’s spoken (and therefore what’s unspoken), and leave the rest up to actors and directors and designers. That’s my goal: can language be both valuable on its own terms, as well as dramatically justified and vital. Now, some might look at the layout of my recent plays and think I’m writing “poetical drama” — and I’m not, I promise! These plays aren’t meant to be performed with any sort of preciousness, as you well know, Tim. Perhaps it’s my middle-aged eyesight, or my above-average-sized ears, but we don’t get close-ups in the theatre; ours is still, even in a 99-seat space like Boston Court, an oral and aural medium. When I was a young writer I would sometimes feel I was on the verge of hysterical blindness while writing. It’s not that I’m writing radio plays, but I’m trying to listen primarily. There’s something spiritual in that, maybe. A little crazy. Hearing voices.

Does the poetry penetrate the playwriting or does the playwriting penetrate the poetry?

It works both ways. I hope my plays have the economy and precision and evocative power (and mystery) of poetry, and that my poems are theatrical, tell a story, capture a living voice or voices. I’m never confused whether something wants to be a play or a poem (or prose, for that matter, which I’ve been known to write from time to time). Even though I often try to dramatize inner states, plays of course happen in public. Poetry, or the kind I usually write, is introspective, reflective; something intimate between the page and the reader. This type of poetry can of course be performed, but it’s still something of an emotional striptease for me, and the audience. All that said, I like tension between the genres: theatre that’s almost unbearably intimate, poems about so-called politics. Life is confusing, so genre should be too.

There is a current of paranormal, supernatural, spiritual, and psychic energy that electrifies your work — though always in tandem with some true story or other. In The House in Scarsdale: A Memoir for the Stage, the protagonist, Dan (the memoir-you) relies on two psychic mediums to ascertain information about the enigma of his family’s dark past. In the docudrama The Body of an American the character Paul Watson, a Canadian photojournalist covering the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia, is famed for the gruesome (Pulitzer-winning) photograph he snapped of Staff Sgt. William David Cleveland’s corpse being dragged through the streets by celebratory locals. He believes himself to be literally haunted by the ghost of Cleveland. The House in Hydesville dramatizes the Fox sisters’ creation of Modern Spiritualism in the early 1800s, a true story that nearly mirrors contemporary society’s famous psychic mediums who become television celebrities and millionaires through their “ability” to communicate with the dead. The Cherry Sisters Revisited commemorates the tale of the sisters’ traveling vaudeville act that was relentlessly ridiculed — so bad that it was good, as it were. They were instrumental in creating the right of the press, of critics, to say slanderous things about performers they reviewed. Yet, in your depiction, the sisters are ghosts, condemned to haunt the mystery of their careers. Can you talk about all this vivid spookiness?

I wasn’t raised with religion. My father was a lapsed Catholic, so a vaguely superstitious form of that probably dribbled down. And I’m Irish(-American), so there’s probably something eerie hardwired. But I’ve always been fascinated by faith, why we believe what we believe and how those beliefs change. Like most things a writer keeps writing about, there are many convergent motivations, only some of them fathomable. My parents were mentally ill and abusive, and they filled our childhood lives with lies and secrets and delusions. I was always, consciously or not, trying to find out the truth. What did they believe? Especially when they were cruel — did they believe they loved us? They claimed to, and I believe they believed they did, but their love so often manifested as resentment, even hate. As Henry James knew, a ghost story is an instinctive metaphor for child abuse. And my abusive parents were themselves abused as children — at least my mother was. So I grew up loving a haunted person. The ghosts in our house were real.

Your writing is almost preternaturally “giving” to an actor. As an actor who has performed in one of your plays (wherein I created some of my most meticulous and visceral work) I can vouch, first-hand, for that sense of “writer-as-giver.” And yet your writing doesn’t follow traditional avenues in terms of easily discerning objective, obstacle, and action. Those fundamentals appear later, like clandestine lovers who reveal themselves to be vampires or mermaids, or worse — politicians. Wax poetic on that, if you will.

Well, I do try to write meticulously, try to discover language and action that can exist in simultaneously realistic and poetic ways. I revise continually, and for a long, long time. Plays that develop along the traditional avenues you speak of usually bore me, and don’t feel much like life; they’re simplifications, and therefore not typically truthful or beautiful. But they are often marketable. Your description above is a kind one. I came to the theatre as an actor, and I still think of plays like an actor. Some writers suggest writing “what you want to see” as an audience member, but I still write what I want to perform, even though I’m no longer acting.

What is life like for you as a successful contemporary American playwright? Do you make money? The theatre doesn’t take care of its practitioners, so how do you survive? In addition, what words of wisdom do you impart to younger playwrights? If there was one thing you desperately needed to get across, what would it be?

I tend not to think of myself in terms of success or failure anymore. I’ve had a lot of therapy. And I’ve had a lot of opportunities, a lot of luck. I’ve struck out too. And I’ve stuck it out. I haven’t written for TV or film, haven’t even tried (with one exception — the subject of my new play New Life, which has to do with my friend Paul Watson’s experience as a war reporter covering Syria, and our tragicomic attempts to pitch said experience as a cable TV “prestige” drama). I’ve avoided more lucrative forms of writing because I know I wouldn’t enjoy it and therefore wouldn’t be good at it. I love working alone, and I need to feel inspired. A Tony-winning Broadway producer said to me years ago: “Well, you’ve got principles.” And she said it sadly. And I never heard from her again. So yes — there’s no money in this. When I first moved to New York I temped the graveyard shift at Credit Suisse First Boston, pretending I knew how to create spreadsheets and presentation booklets for stressed-out junior bankers. Now it’s just a mix of production and publication royalties, commissions, grants and fellowships, the odd prize, and teaching here and there that keeps me financially afloat. I’ve always thought of applying for grants and fellowships and residencies as a significant aspect of my job as a writer, and it’s often paid off. All that said, I wouldn’t be able to live in Santa Monica with a daughter and a schnauzer if my wife didn’t work in Hollywood. Acting and writing in TV and film has always been her ambition, so there’s no compromising here. Oh, and you asked about the one thing, a bit of advice for a young writer: don’t take advice. How to write, how to “be a writer,” is different for everyone, wonderfully so. So keep discovering your difference. Which sounds like advice. So I’ll stop now.