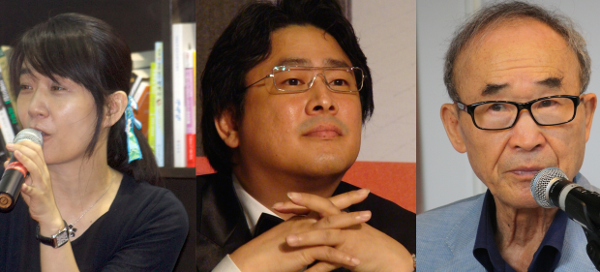

The notion of an artist blacklist evokes the ugliest chapters of the Cold War more than the practices of a developed 21st–century democracy, but South Koreans have recently had to come to terms with the fact that, for nearly the past four years, they’ve lived under a state that has seen fit to maintain one. Or at least they’ve lived under a president who felt she couldn’t do without one, and now that she faces impeachment, the names of over 9,000 people her administration has secretly denied official support have come out. They include Han Kang, author of the Man Booker International Prize-winning The Vegetarian, popular filmmaker Park Chan-wook (whose crowdsourced collaboration with his brother Bitter, Sweet, Seoul we featured on the Korea Blog last year), and poet Ko Un, South Korea’s best-placed contender for the Nobel.

“It’s an honor to be on the list,” a New York Times piece on the blacklist quotes Ko as saying on an SBS broadcast. “This shows how disgusting the government is.” It also shows, in a way, that art retains a power here that it lacks in the West and especially in America, where if poetry of the kind that Ko writes and novels of the kind that Kang does get discussed in this context at all, their inability to make a real political impact is a foregone conclusion. But Park Geun-hye has never taken criticism well, and any work even vaguely interpretable as an attack on her actions or those of her father, who ruled as a developmentalist strongman from 1961 to 1979 with censorious policies of his own, could well lose its author access to government resources.

Kang’s Human Acts, on the Gwangju Democratization Movemement violently put down in 1980 not by Park’s father but by his successor, seems to have irked Park enough to deny Kang the expected official letter of congratulation when she won the Booker for The Vegetarian. “Rather than be disappointed,” writes the Kyunghyan Shinmun‘s Choi Wu-gyu, “she may be happy to have gained material for a new novel,” and a heightened reputation for risk-taking dissidence will certainly benefit the international profiles of many other of Korea’s blacklisted writers, directors, painters, actors, directors, and musicians. It reminds me of Clive James’ view, stated in jest though stated fairly often, that there’s only one way to make poetry popular with the young: “to ban it, to make it a criminal offense to own it or deal in it.”

But what threat has Park’s government, democratically elected and thus theoretically without quite so much need for thought control as a more self-empowered regime, seen in all this? Its anxious attitude represents less of a departure from the overall condition of modern South Korea, whose laws have long favored stability over truth. Straightforward treatment of history, for instance, has struck fears of delegitimization into the hearts of its governments since the nation’s founding in the aftermath of World War II, but Park takes it to another level: the very first protest I attended in Seoul directed much of its outrage toward its revisions of school textbooks meant to give quite a different impression of Korea’s recent past than one might draw from, say, the work of a Ko Un or a Han Kang or a Park Chan-wook.

The year 2017 will see South Korea pass the 30th anniversary of its democratization and, aptly, will also see it kick out a president dynastically tied to its pre-democratic past. This will presumably involve tearing up her blacklist or blacklists, though that hardly guarantees that her successor won’t also draw one up.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Anti-Trump Protests, Anti-Park Protests, and the Koreanization of American Politics

America Has School Shootings, Korea Has Sinking Ships

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.