I dream of my breasts. They’re sizzling at the edges in an enormous frying pan and the pale skin of each breast is now translucent, like the white of an egg as it begins to cook. A technician in a white coat, her back to me, stands at the stove. She lowers the heat and jiggles the frying pan with a practiced hand. You can get dressed now, she says airily, brandishing a metal spatula. This morning I am slated for a mammogram. I fondle my breasts, warm and sleepy, through my pajama top. Today is their big day. My partner stirs, reaches out for me, encircles my body, places one hand lightly on my breast. I push his hand away and curl up like a creature in a biology experiment. Not now, I mumble into the pillow.

I jump into the shower and soap myself down. I shave my armpits with his razors and then wipe it carefully so he won’t know. I want to smell nice when I strip off for the technician, I want my armpits flawless when the doctor tells me to lift my right arm over my head.

I dress for the occasion: a bra with a single clip at the back and an oversized sweater — easy to pull off, easy to put back on.

Rain begins to fall as I approach the hospital so I break into a run, the wind whipping my face, my breasts bouncing softly up and down inside my sweater. Then I slow down, climbing the stairs to the Women’s Health Center. I know the way: four years ago a lump was discovered in my right breast and since then my breasts and I have been invited back every year for a mammogram, sonogram and squeeze, in that order.

The waiting room is a spacious area with easy chairs, well-thumbed magazines from 2017, and a TV screen with the sound turned off, pumping out news and weather. Beyond it, a suite of examination rooms. Every time a number is called out, we all look up, check the green tags we have obediently strapped to our wrists, settle back into our easy chairs. Finally, my number is called out by a voice through the door, again and again, as if I am late.

The technician, a heavily pregnant young woman, checks my name tag and points in the direction of a chair in the corner of the room. Take off your clothes. Just your upper body, not your jeans, she says, leaning over the computer screen, her belly straining.

Dressing and undressing, an act most of us do every single day, is an intimate activity. The lifting of the arms to remove the sweater, the reaching out to unclip the bra, the breasts sagging and dopy, their starring role as sole providers of nutrition to my three babies long over and done with. I have always thought my breasts look better dressed than undressed. My breasts were never like those mentioned in Song of Solomon — two fawns, twins of a gazelle, grazing among lilies.

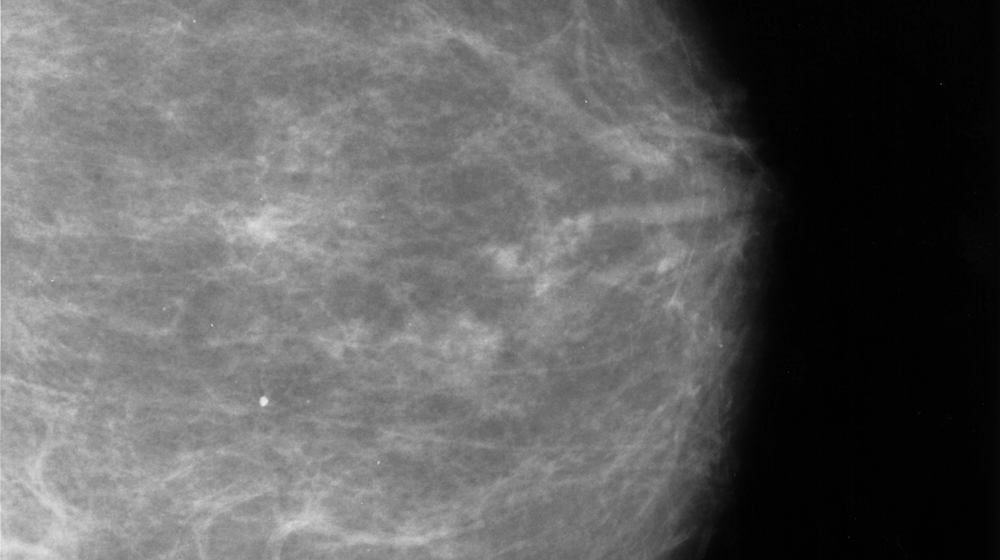

Bare-chested, I approach the instrument of torture. I plop my right breast like a sac of blubber on the tray. The other breast hangs down dejectedly. The technician lifts my right breast and maneuvers it into the correct position, yanking it further forward onto the shelf. A Perspex tray lowers down onto my breast, compressing it over the lower tray. It no longer looks like my breast. The nipple is stretched out so much it has disappeared. Thinking about my breasts as a sexual commodity could not be further away at this moment. One side of my face is thrust up against the machine. Don’t move, she says, and walks back to the computer screen. How could I? My breast is trapped, pinned down like an ugly butterfly. The top tray crushes my breast even more for about ten seconds. Everything okay? the technician asks.

There is no room for La La Land here, no way to imagine myself in a happy place. I am good at doing this when I go to the dentist or gynecologist because there it is much more difficult to actually see what is going on. Here, it is impossible not to see, pushed up against a giant machine with one breast flattened to unreal proportions.

When I was a kid, we used to walk along the promenade in Blackpool, England, during school holidays with my aunt, who lived in this seaside town. There was plenty to do there: slot machines, carousels and ghost trains. But what interested me the most was the Ripley Would You Believe It Show, where, allegedly, there were all kinds of weird and wonderful spectacles: a two-headed calf, authentic shrunken heads, the tallest man in the world and other freakish sights. And now I am privy to my own freak show – a breast the size of a giant flapjack.

Today, it is standard procedure in the modern world for women to have their breasts checked regularly after the age of forty. Those with a history of breast cancer in the family, if they are lucky enough to have good health care, will do this much earlier. I have a small, benign lump in my right breast, marked by a titanium chip that was shot into my breast the day the lump was discovered and a biopsy was performed. The titanium chip and I live in harmony together. I go back once a year to have it checked, just to be sure.

I am writing about my experience not as something unique or special. On the contrary, I am writing about it because so many women go through exactly this. And I am lucky, I know, because this is where it begins and ends for me. I enjoy a clean bill of health, make an appointment for next year, go off to my life.

Later, fully dressed and drinking coffee with my partner in the university cafeteria, I try to explain to him what it’s like, this routine examination, this tip of the iceberg for so many women. Think of someone maneuvering your penis into a 90-degree angle, I offer, and then trapping it for ten seconds or so. Something like that.