By Joanna Chen

I don’t support rallies for peace and I don’t belong to any peace organizations. Working in the Jerusalem bureau of Newsweek for 15 years conditioned me to stand on the sidelines, and simply observe. I followed with intensity everything going on around me. From 1999 until 2011, I reported on rallies in Tel Aviv, Hebron, and Jerusalem.

I talked to people on the street, genuinely interested in opinions on both sides. I drove all over Israel and the West Bank, and checked the wires several times a day for developments. I met Jewish settlers, talked to Palestinian officials, hung around the tent of Peace Now, spent hours in Ramallah and Bethlehem.

I knew I was privileged to be able to cross over these boundaries with my foreign journalist credentials, and eventually felt like I had a pretty good grasp of what was going on. I became cynical, convinced that the peace was something that would always be out of reach to those living here. Palestinians and Israelis, Jews and Arabs, would continue to live side by side, but never in harmony.

This sense of cynicism has remained with me, five years after leaving journalism. The other day my husband reminded me how we went to a demonstration in Tel Aviv back in 2008, to protest the Israeli siege on Gaza, and how I literally stood on the sidewalk while he joined the crowd surging toward Rabin Square. Looking back on this, I think it was simply easier for me to fall back into my role as observer, rather than taking a stand. I did not believe in the power of rallies, nor did I believe that any of the peace negotiations, covert or otherwise, would bring about peace.

But l continue to believe in the importance of understanding the other side, of facing up to what lies ahead, and attempting to bridge that gap, and to break down the walls that have been built. So I continue to write, and as I do the words of Denise Levertov’s Making Peace ring in my ears:

But peace, like a poem,

is not there ahead of itself,

can’t be imagined before it is made,

can’t be known except

in the words of its making,

grammar of justice,

syntax of mutual aid.

Last month, when a girlfriend asked me to join her at a meeting of Palestinian and Israeli women in Beit Jalla, I was intrigued. Suha abu Khdeir, the mother of Mohammed, burned to death by Jewish extremists in 2014, was scheduled to speak there.

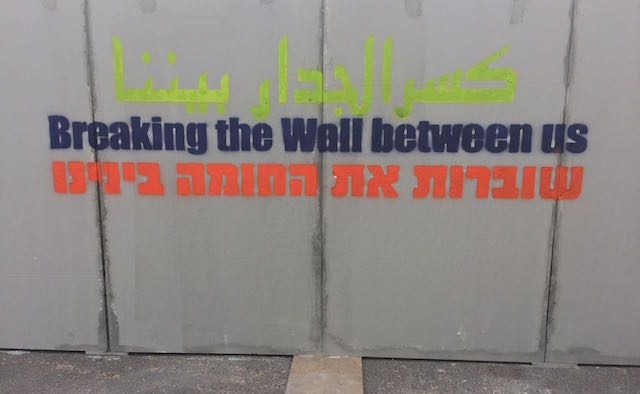

It had been another busy week for me, and I was planning to spend the weekend catching up on work. I stalled, told my friend I there was no way I could make it. It was a day-long meeting organised by the Bereaved Parents’ Circle, planned over International Women’s Day. There would be speeches, and a mock wall dividing Palestinians and Israelis would be covered in graffiti and then broken down, symbolic of the wish for the two sides to live together. Finally, a silent march for peace was planned, the women standing together in solidarity.

There was no way I was going to hold a plastic hammer, break a carton wall, or make-believe that peace was just around the corner. There was no way I was going to take part in any touchy-feely activities.

But I couldn’t get Suha abu Khdeir out of my head. I remembered her son’s murder, carried out in retaliation for the abduction and murder of three Jewish teenagers. She deserved my attention; she deserved my respect. If she was prepared to stand up and speak out, if she was willing to still talk to the other side, I could at least do her the honor of listening.

I left the house late, scrambling to get everything done before finally jumping into the car and driving off. I arrived late to pick up my friend, but she just laughed. Things always start late in the Middle East, she said. We drove along the road that bypasses the Palestinian village of Husan on the one side and the Jewish settlement of Beitar Ilit on the other. Just before the Israeli checkpoint that divides the West Bank from Jerusalem, we turned right and drove up the hill to the Everest Hotel in Beit Jalla. The parking lot was still fairly empty, and a group of Israeli women dressed in black were making their way on foot to the hotel entrance.

I hung back for a moment. Perhaps this wasn’t such a great idea. I didn’t want to be identified with these women, and I wished I had stayed at home. We’re already here, my friend said, gently steering me towards the courtyard of the hotel. I signed up, received a set of headphones so I could receive simultaneous translation from Arabic, and I was given a sticker with my name written on it in Hebrew and Arabic. I stuck it gingerly on my sweater.

Inside, the hall was already filling up, and women were helping themselves to mint tea and cookies. I could immediately see who was who: the Palestinian women were mostly dressed modestly, their heads covered; the Israeli women wore jeans and sweaters. We chose our seats carefully, sitting down next to a Palestinian woman who, I quickly learned, spoke no Hebrew or English but gave me a shy, hesitant smile and moved her bag off the chair so I could sit next to her. We read each other’s nametags, we said them aloud and I mumbled the few words of Arabic I knew, annoyed at myself for not persevering at Arabic class.

In the row before us, a group of young women in black scarves took a selfie of themselves, smiling and chattering together. The photo included me, sitting behind them, clutching my bag. One of them turned around and showed me the photo and we all laughed, and the tension broke a little. They were from Hebron and had come to Beit Jalla by bus that morning. There had been no need for travel permits from the Israeli military since Beit Jalla is within the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority.

Perhaps this was the reason why there were so many Palestinians at this meeting. It was accessible, it was for women, and it was at the weekend. This was not one of those meetings where a token Palestinian appears among a mass of Israelis, so often the case when the venue is in Israel.

A hush fell over the hall as the speeches began, first a Palestinian representative of the Bereaved Parents’ Circle, and then an Israeli. “Feesh kalimat,” “ayn milim,” there are no words, said the Palestinian woman, whose son was killed by Palestinians several years ago. But there were plenty of words that day, and a young woman in jeans and a blue jacket stood to the right of the hall, translating those words as they floated across the hall. This, for me, is the grammar of justice and peace.

As Suha abu Khdeir approached the stage, I leaned forward in my chair to see her, a woman whose 16-year old son was snatched away, beaten, doused in gasoline and set alight. She stood there, opened her hands in a gesture of prayer, and bowed her head. The audience rose to its feet, following her cue, and for a moment there really were no words, just a deep sense of sadness belonging to the two hundred women who filled the hall that morning. She talked quietly about reaching out to the other side. She paused between sentences, and the voice of the translator continued in my ears, at times choking up, as if she could not get the words out or do justice to them. Perhaps this is what Denise Levertov was describing in her poem.

A line of peace might appear

if we restructured the sentence our lives are making,

revoked its reaffirmation of profit and power,

questioned our needs, allowed

long pauses…

When she finished speaking, my friend and I apologized to the women sitting in our row and squeezed our way out. No, we were not staying for the rest of the event. We stood together at the back of the hall for a few minutes before leaving, no longer a part of the gathering but rather observers. On the way back, we passed Talitha Kumi, a school where peace movement Combatants for Peace were holding a meeting with actor Richard Gere. Perhaps these meetings are just a drop in the ocean, but still they take place, and surely that counts for something.

As I drove home, I thought of the young women from Hebron who had sat in front of me, snapping photos that morning. I thought of my own face, hesitant, smiling, unwilling to be identified, on that phone screen, and I wished I had asked them to send me a copy.