I intend, in the fullness of time, to give Korean literature at least its fair share of coverage here on the Los Angeles Review of Books‘ Korea Blog. But where best to begin? Readerly types newly arrived in Seoul might well ask the same question about how to take a first step into the realm of letters here, and in response I would direct them to the Seoul Book and Culture Club, keep-uppable with online through either Facebook or Meetup.

Hosted by Scottish expatriate cultural impresario Barry Welsh (whom I interviewed last year on my podcast Notebook on Cities and Culture), the Book and Culture Club has put on live events with such literary luminaries as poet (and prime Korean Nobel Prize candidate) Ko Un, Please Look After Mom author Shin Kyung-sook, I Have the Right to Destroy Myself author Kim Young-ha (whom I profiled here in the LARB), The Vegetarian author Han Kang, Native Speaker author Lee Chang-rae, and Drifting House author (as well as another interviewee of mine) Krys Lee, all of which they conduct bilingually, in both Korean and English.

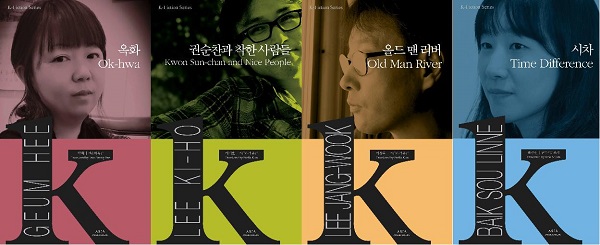

Just last weekend I attended a Book and Culture Club event which gathered onstage four young Korean writers (“young” meaning, given the high barrier to entry of Korea’s literary scene, younger than fifty) for a discussion of the direction of Korean fiction today, all of whom now have a novella out in a dual-language edition from ASIA Publishers. Lee Jangwook, a poet, critic, and Russian literature specialist in addition to his work as a novelist, wrote Old Man River (올드 맨 리버); Lee Kiho, who specializes in telling stories of societally marginal characters in unusual forms, wrote Kwon Sun-chan and Nice People (권순찬과 착한 사람들); the Korean-Chinese Geum Hee, whose work focuses on the lives of North Korean refugees, wrote Ok-hwa (옥화); and Baik Sou-linne, who grew up in Paris from junior high on, wrote Time Difference (시차).

It might seem an odd choice to introduce writers to the Anglosphere with novellas (and short novellas at that), a form that English and American readers never seem quite sure what to do with. But if you want to understand Korean literature, you have to understand the place of the short form. Lee Kiho, the most famous author of the bunch, explained that short novels have the importance they do here not despite the fact that they don’t sell well, but “because they don’t sell well,” creating the perception that, unlike longer novels, “they’re not under the influence of capitalism.” (Plus, he added, “they’re more convenient for the writers” — no small matter.)

In the interviewer’s chair sat Charles Montgomery, teacher in the English Interpretation and Translation division of Seoul’s Dongguk University, editor of KTLit.com, and just about the most enthusiastic American (or otherwise) advocate for Korean literature in translation I know. (I also happen to have interviewed him myself on Notebook on Cities and Culture.) He lead the writers into a conversation that ranged widely, especially in the geographic sense, given that most of them had written stories set in or involving (or came with the personal experience of living in) lands outside Korea. An underlying question: has Korean literature truly begun to internationalize?

Lee Jangwook suggested that it might simply have begun to reflect the age of global capitalism in which we find ourselves. Baik Sou-Linne pointed to the current rise of “traveling novels” in Korean literature, mentioning the increasing proportions of Koreans who, like her, lived abroad at an early age. It all made me think of Douglas Coupland’s definition of the relatively new genre of “Translit,” composed of novels that “cross history without being historical; they span geography without changing psychic place. Translit collapses time and space as it seeks to generate narrative traction in the reader’s mind. It inserts the contemporary reader into other locations and times, while leaving no doubt that its viewpoint is relentlessly modern and speaks entirely of our extreme present.”

Yes, I would very much like to read Korean Translit, especially of a kind this latest generation of writers could well master. But would Koreans themselves like to read it? Montgomery brought up the OECD-collected statistic that, despite Korea’s impressively high literacy rate, it ranks poorly indeed in terms of how much reading its citizens do for pleasure. In this as in other areas of culture, more attention from the wider world — increasingly drawn, I would think, by a more history-spanning, geography-spanning outlook on the part of the writers — might stoke more attention back home. Korea’s promoters have long shown an obsession with the country’s international rankings (especially its sometimes unflattering OECD rankings), and perhaps that will bring those lagging pleasure-reading numbers up.

Or maybe we just need a better definition of reading. Lee Jangwook described the established notion of “good reading” as, quite possibly, nothing more than a stereotype. Maybe, he argued, it can involve something other than alone time with a paper book; maybe it can happen online too, and maybe the amount of active discussion, criticism, and knowledge that results from it counts as much as the volume of reading done in the first place. The very role of literature, added Geum Hee, has changed: it doesn’t tell you what to think anymore, but gets you to reflect on your life. Nobody argued against the idea that the time of the writer as societally anointed “grand master,” seemingly prolonged in Korea, has ended. In the straightforward words of Lee Jangwook, “It’s about time we burst that bubble.”

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.