How do you convince someone to spend their limited travel time and money in Seoul? The officials tasked with promoting South Korea abroad have racked their brains over that very question for years and years, coming up with little in the way of sure-fire selling points for their capital city. Even aside from the formidable challenge of competing against name brands like New York, London, and Paris, Seoul struggles to positively distinguish itself, even in broad strokes, from the other metropolises of Asia. The integration of a deep-rooted culture with advanced technology? Tokyo has long had that image sewn up. Rapid change? Beijing changes faster now, for better or worse. Cheap food and a pleasurable nightlife? Sure, if you’ve never heard of Bangkok. Ease of communication? Don’t get any given tourist started.

They don’t really come to Seoul for its the renowned cultural institutions or its distinguished architecture, and certainly not for its history or diversity. What, then, makes this city so very compelling? I’ve had plenty of similar conversations about Los Angeles, another city which provokes in me (and a select but growing number of others) a fascination bordering on obsession, but whose appeal doesn’t always present itself to the first-, second-, or even third-time visitor. In the cases of both Los Angeles and Seoul, the answer always comes down, unsatisfyingly though it may sound, to a kind of unromantic vitality: though the basic elements of both cities can seem dull, dysfunctional, and even dangerous, the life lived among them, filled with boundless amounts of energy often flowing at cross purposes, offers a bottomless and ever self-refreshing subject of study.

In Seoul, few see this as clearly as Michael Hurt, a Korean-black American photographer who grew up in Ohio and first came here to live in 1994 as part of the Fulbright English Teaching Assistant Program. After completing a graduate program in comparative ethnic studies at UC Berkeley in 2002, he returned to Korea and spent the next few years taking his camera to the streets in a serious way, capturing whatever struck him as the real visual and social texture of life in the city. Street photography had already established itself in Los Angeles and other cities across America and Europe, but in Seoul, apart from a cameraman named Kim Ki Chan who documented neighborhood activity in the 1960s and 70s, it remained a virtually unknown tradition.

“Outback Girls” (2004)

Hurt shot all the pictures selected here during the early 2000s, the most street life-focused period of his photographic career. The image just above comes from a time, he says, “when I began noticing that Outback Steakhouses were a highly gendered space, dominated by twentysomething women.” This led to the realization that “what Koreans called ‘family restaurants’ were actually spaces for young women to socialize. This is about when my camera going in the direction of ‘gender performance’ and young women.” His photography and research in those areas has since led him to develop the field of visual sociology with Korea as a subject, a project further documented at his site Deconstructing Korea.

“Post-Protest” (2003)

“I took this in after one of the big anti-American protests in Gwanghwamun,” Hurt says of the image above, “when the streets were blocked off but people were still milling about, lending a street festival-like vibe only extant for short periods of time.” I’ve come to Korea at a far less anti-American era, but should that sentiment arise again, it would no doubt make itself felt in this very same monument-scaled downtown space. “It’s no coincidence that Gwanghwamun was the site for the 2002 World Cup festivities and the big anti-American demonstrations. It was a natural site for mass gatherings charged with strong emotions,” whether of celebration or condemnation.

The name Gwanghwamun refers to the main gate of Gyeongbokgung Palace, the reconstructed 14th-century compound that Seoul promotes as a prime tourist attractions. Some visitors find it interesting and some don’t, but I always like seeing a historical (or at least historically styled) structure amid a forest of gleaming high-rises. This makes me a predictable Westerner in Korea, since our eyes tend to get caught by all the old-and-new contrasts the city offers up, such as the one above. “I came across this dude standing there looking like he had stepped out of time machine,” Hurt says of this 2002 shot. He liked it at the time, but having realized the cliché inherent in the contrasts, admits that he’s “not very into this picture anymore” — but I, a much more recent arrival, still am.

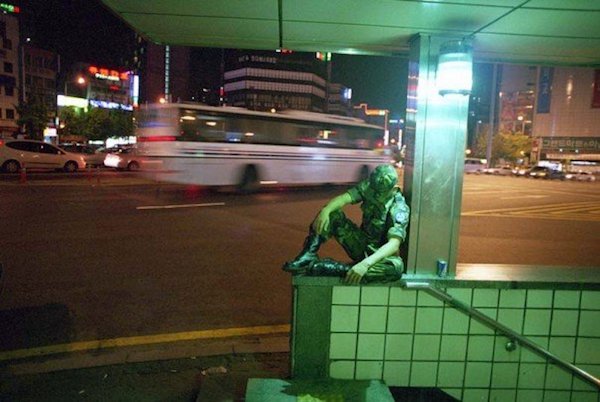

“Furlough” (2002)

While no longer as militarized as it was in the decades right after the Korean War, South Korean society still has a faintly martial tint that might surprise and even discomfit travelers from the West or other east Asian countries. Some of this has to do with the constant presence, here and there, of uniformed young fellows enlisted in their mandatory military stint but temporarily free to go out on the town. The picture above captures a moment when Hurt passed by one such soldier “who had seemingly taken his short leave from the military a bit past the limit. I slowed down the shutter and held the camera steady to get the motion in the back, which added a dreamy feel.”

“Seoul Nights” (2003)

Those who would object to the portrayal of one of the country’s defenders in such a defenseless state might have an even stronger objection to the picture above, which Hurt snapped on the way through Seoul Cheongnyangni 588 red-light district. “This was when prostitution was getting into the news,” he remembers, “and the statistic that the industry was four percent of the GDP was getting some play, but there was still a strong social dislike for bad news about Korea, and this picture was flagged as ‘anti-Korean’ when I exhibited it.” But urban redevelopment has had its way with Cheongnyangni, as with many other neighborhoods, hollowing out the venerable 588 — as much an institution, in its way, as Gyeongbokgung.

“One Night in Hongdae” (2013)

In Korea, as Hurt well knows, depictions of “bad things” about the country can hit a nerve (“good things,” by contrast, can include sights that play up the glories of the country’s distant past, the modernity of its buildings, its bounty of upscale commerce, and its industrial and technological prowess). But nobody can actually extricate the “bad things” about any place worth visiting, let alone living, from the “good,” and Seoul provides just about the richest mixture of the two going today. The more recent picture above, taken in the youth-oriented art-school district Hongdae, provides a rich glimpse into the Seoul experience, capturing, as Hurt says, “what Henri Cartier-Bresson would call the ‘decisive moment.’ All the elements come together, and catching it requires a real feel for and knowledge of both the area and the people within it, combined with an instinctual familiarity with one’s equipment and the technical limits of one’s camera to capture that moment when it happens.”

In this case, Hurt explains, “you have to already be pushing the shutter button when she upchucks, having known she was going to do that before the fact. This is quintessentially Hongdae on a Saturday night, no matter what anyone says about this being a ‘negative image of Korea’ — which it most certainly is not. It is just a fact of life and a part of the culture. This is a shot across the bow to anyone who only wants the world to know about Korea as what I call ‘Arirang and hanbok.’ Korea is what it is, and it ain’t always fan dances and fairy tales about fishermen. This picture is me ‘keeping it real.’ That’s the only thing I ever wanted to do with my camera in Korea.”

You can see more of Michael Hurt’s photography on Instagram and Flickr, and in future posts here on the Korea Blog.

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.