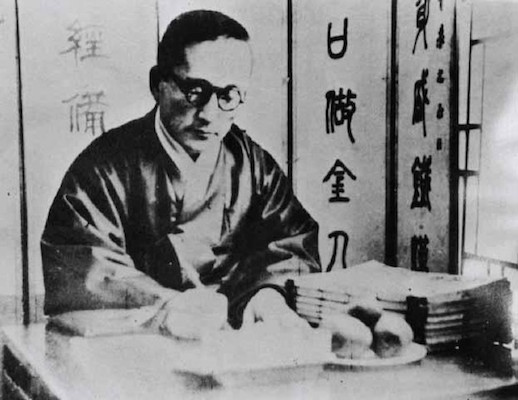

Yi Kwang-su (pictured above) has been mentioned here before for his theoretical contributions to modern Korean modern literature in the early 20th century as well as for his wandering political eye. As a writer of some repute best known for the novels Heartless and The Soil (흙), the latter of which which is, to my mind, the spiritual progenitor of the modern Korean drama. Yi’s stories are laced with love triangles, betrayals, defeats, revenges, and The Soil brings in a spectacularly failed suicide attempt as well. Doomed lovers make promises they can’t keep, wealth differentials grind people into dirt, and “true” heart and dedication (according to Yi’s model) bring no tangible rewards.

You can now catch all of this, a reader notices, most every night on television in Seoul. A reader also notices that this book is big — some 510 pages big, and that can be daunting. On the other hand, having originally been published in serial form (as much of Korean fiction was prior to the 1960s), it is broken up into convenient little chunks, with some mini-chapters barely clocking in at over a page. While perhaps not the book that a potential reader of Korean fiction would start with, The Soil does have its charms. Once a reader gets past the large cast of characters and number of plots, all introduced at a lickety-split rate as the book opens, the story begins to flesh out. Despite the book’s length, I read it in just two sittings.

Unfortunately, and particularly at the beginning, Yi breaks the cardinal rule of authorship and “tells not shows”: non-sympathetic character’s actions, even quotidian ones, ate directly described as “arrogant” or improper, while those of sympathetic characters are described as noble or appreciative. This is an odd shortcut in a book of so many pages, and thankfully this tendency fades a little as the story continues. In addition, getting the host of characters sorted is initially tough, but for the reader who perseveres, the melodramatic nature of the book actually becomes interesting, and the absurd saintliness of some characters and the moustache-twirling evil of others becomes fun to watch.

The plot is convoluted. A young man from the country named Heo Sung leaves his hometown (and first love) to become a lawyer. His essential goodness, however, derails him, as his employer in Seoul decides that Heo should marry his daughter. In a way it is a happy story, indeed the quintessential success story in Korea: move to Seoul, marry well, get rich. But not for Heo, who sees the city as essentially corrupt, longing to go back to his simple village and, as part of the grand Korean nation-building project, restore it to economic and social health. After a series of scenes that reveal moral corruption of Seoul, and the evil of foreign influences within (this is somewhat odd, since Yi was necessarily drawing on foreign models for his modernism, and as a speaker of both Japanese and English was very international himself), Heo returns home and begins to rebuild his village in a cooperative fashion. He leaves Seoul behind, and two other characters behind in it: the Japanese collaborator Gap-Jin and the even more morally corrupted Dr. Lee, whose sin is to have been educated in the United States.

At first things go well in the village, but of course the forces of reaction kick in and turn it into a battleground. There plays out the rest of the story, along with various love triangles, interpersonal intrigues, and didactic passages about what “should be done.” The pages fly by as the plot unwinds, but the ending is a bit of an ideological deus ex-machina, which disappointed me a bit. Though it absolutely does not follow from the first 500 or so pages, the sudden divergent ending is not uncommon in Korean fiction. Yi more or less had to write this kind of ending, because without it, the entire social project of the book would not have made sense. Suffice it to say that Sung’s essential goodness grows too vast for the rest of the universe to fight, and the traumas of the foregoing pages are swept away by the inexorable progress of the modern world.

That’s a bit of an ironic ending, considering what was to happen to Yi himself when that “modern” future actually came. A bit of an odd duck, and in some ways one of Eric Hoffer’s “true believers,” Yi jumped from ideology to ideology, or maybe from power to power. Orphaned young, he spent some time in Japan, became both an early fighter for Korean independence and the father of Korean modern literature, converted to Buddhism in the early 30s, and was then jailed by the Japanese in 1937, an experience from which he emerged as, curiously, a full-fledged collaborator. As the North Koreans retreated from Seoul during the Korean War, they gathered up a group of intellectuals from the South to take with them, and Yi was among them. He did not survive the experience, reportedly dying in a North Korean camp in 1950.

The Soil‘s English translation, by the husband and wife team of Hwang Sun-ae and Horace Jeffery Hodges, is quite good. There is an occasional tendency towards passive constructions (more than likely present in the original), but for the most part it flows in perfect accord with the story, making the reading a pleasure. For readers interested in learning about the social and economic struggles of Korea after the turn of last century — and for fans of broad characters in melodramatic situations — this is an excellent book that, once sets its pins up, wastes no time knocking them down, repeatedly and from all sides. The book itself stays standing, as a kind of manifesto for modernism and a window into the optimism that Korea possessed, ever so briefly, at the start of the last century.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Bright Lies, Big City: Korean Authors and Seoul

Enlightenment and the Birth of the “Modern” Korean Novel

A Rare Korean War Story in How in Heaven’s Name

Charles Montgomery is an ex-resident of Seoul where he lived for seven years teaching in the English, Literature, and Translation Department at Dongguk University. You can read more from Charles Montgomery on translated Korean literature here, on Twitter @ktlit, or on Facebook.